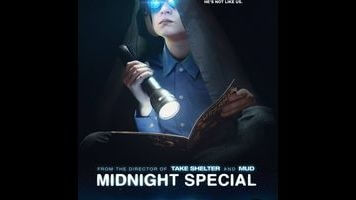

Midnight Special is a unique blend of chase flick and sci-fi parable

In the opening scene of Midnight Special, two armed men sneak a boy out of a motel room and into a customized ’72 Chevelle before peeling off into the dusk. The mulberry sky turns blue-gray with twilight, and then pitch black. The driver hits a toggle switch wired behind the steering wheel, cutting off the headlamps and taillights. The car disappears into the darkness. It will be about 40 minutes before the viewer even finds out how the men, Roy (Michael Shannon) and Lucas (Joel Edgerton), know each other, though by then they will have ditched the Chevelle for a plumber’s white Ford Econoline van and, later, an Isuzu Trooper. Midnight Special is very particular about its cars, just as it’s very particular about its setting—the gas stations, motels, and working-class suburbs of the Bible Belt—and the cautious speech of its characters. In every other respect, Jeff Nichols’ compelling sci-fi chase film is terse and elliptical, showing little and telling less.

It was Nichols’ sophomore feature, Take Shelter, that first brought attention to the writer-director. It starred Shannon as a construction worker in Lorain County, Ohio, who is troubled by visions of an impending apocalypse. The film introduced Nichols’ unique take on contemporary Americana; it was part Old Testament, part psychological character study, set in a flat landscape dotted with propane tanks and pick-up trucks. Midnight Special, nominally about a supernaturally gifted child pursued by the government and by a Texas doomsday cult, is more of a genre piece than anything Nichols has done, carried by its steady momentum and its engrossing sense of mystery. It has car crashes, shoot-outs, and bursts of digital effects, but is carefully minimized, its mood set and sustained by the score’s piano motif, a repeated bum-dum-da-dee-da-dee-da-du-da-du. It is plainspoken in its treatment of the fantastic. It knows its metaphors.

Take the Chevelle. Its unfinished coat of primer gray betrays it as a project car, which is to say, the kind of thing a man puts off, presuming he’ll have all the time to finish it, and then finds himself pressed to use. Perhaps one could even read the movie’s odyssey of cars as a play on its theme of parental responsibility: the dream car, never to be finished, swapped for a work van and then a mid-size SUV. The bad guys trace it through an insurance bill left on a kitchen counter, because even Midnight Special’s sense of conspiracy is grounded in the commonplace. The only explicitly poetic line the movie allows itself is spoken by the cult’s neckless goon, played by character actor Bill Camp. Sitting in his truck, he says, “I was an electrician, certified in two states. What do I know of these things?” This is the most the viewer will ever learn about him. Midnight Special defines characters through what they can’t understand, contrasting fear of the unknown with faith in it, and flipping the supernatural into a metaphor for the everyday.

There is the boy, Alton Meyer (Jaeden Lieberher), who can hear radio and satellite transmissions in his head, and is able to make walls churn and crumble in fits during which beams of bluish-white light flare out of his eyes. It is said that daylight is dangerous for him; he gets around at night, protected by swim goggles and safety earmuffs. One of the few things Midnight Special reveals immediately is the fact that Alton is Roy’s son. He is a child who must literally be kept away from the world, completely mysterious to his father and headed for a destination that not even he is sure of. Roy and Alton’s mother, Sarah (Kirsten Dunst), were both raised in the cult. It is referred to only as “the Ranch,” and shown through the most banal imagery of the American fringe: corrugated compounds, sermon halls lit in unflattering fluorescent, women in plain prairie dresses. It looks like a real cult, in other words. Just about everything in Midnight Special looks like a real something.

Not that the movie is lacking in artifice and style. Nichols’ love of empty visual space, present in his earlier films (Shotgun Stories, Take Shelter, Mud), is put to use in simple but effective compositions and contrasts that bring to mind John Carpenter. This is a suggestive emptiness: a car racing down an empty rural highway, creating suspense; a sky that hangs ominously over a gas station, and then begins to fill with the fiery ribbons of a spy satellite breaking up in the atmosphere; people standing in empty fields and clearings in anticipation of the supernatural; the spotless white space of the test room of a secure government facility; the camera pivoting around NSA analyst Sevier (Adam Driver) as the massive hangars of an Army base flicker on one after another, readying for pursuit.

There are very important small touches, like the way the film distinguishes Lucas and Roy visually by dressing the former in shades of khaki and the latter entirely in denim, which links him to Alton by way of the blue plastic goggles the boy wears through most of the movie. These are shades of the same color, one worn and faded, the other bright and shiny. Eventually, one begins to wonder whether there’s anything in Midnight Special that doesn’t play a part in figurating Roy and Alton as the archetypal parent and child. The boy must (again, literally) be protected from the world, and from the oppressive upbringing of his parents. The Ranch is led by the smug Caleb Meyer (Sam Shepard, typically excellent), who adopts his followers’ children and is, perhaps, the father every parent fears becoming. Sevier, the analyst, is rarely seen without a backpack and rumpled blazer, bringing to mind a teacher or social worker; he is introduced interviewing cult members in a school lunchroom.

It’s very Spielberg-esque, though if there’s an art to not putting too fine a point on something, Nichols is coming very close to mastering it. Some early scenes and plot points don’t click until later in the film, and then, the way they fit is often de-emphasized; they become private discoveries for the viewer. One can take issue with Midnight Special’s climax, which shows more than the audience has been primed to expect from the film, while leaving most questions unanswered. Like the end of any breathless chase, it can’t help but feel like a slight letdown. But it’s still poignant. Shannon, best known for playing weirdos and crazies, is uniquely good at playing restrained everymen, and he inhabits the role of Roy as a man of unspoken internal conflicts and complicated feelings.

“You don’t have to worry about me,” says Alton late in the film. “I like worrying about you,” responds Roy, succinctly and poignantly defining the best of parenthood in a single line of dialogue. The parents’ relationship to Alton is Midnight Special’s destination, and it’s carried there by Nichols’ measured style and an embarrassment of wonderful performances: Edgerton’s laconic but complicated Lucas; David Jensen’s small role as a fellow exile from the Ranch; Driver’s funny, sympathetic Sevier; and Dunst’s Sarah, who seems secondary at first, but becomes the emotional focus of the final act, unexpectedly conveying tumult and catharsis in a single climactic reaction shot. Midnight Special’s ending dispels much of its potent mystery and tension; it risks coming off as ridiculous to try for the transcendent. There are many moments when it reaches it.