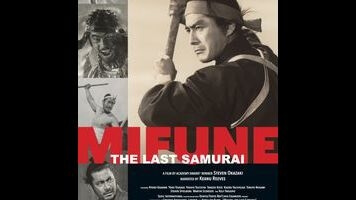

Given that the Toshiro Mifune biographical documentary Mifune: The Last Samurai is only 80 minutes long, it’s a bold choice by director Steven Okazaki to wait until 15 minutes into the film to get to the birth of the man himself. The doc’s introductory passages don’t trace Mifune’s family lineage; instead, they cover the importance of the samurai to Japanese history and popular culture, and trace the origins of the “chanbara” film to the earliest days of cinema. Named to evoke the sound of swords clashing against swords, chanbara pictures relied on stock characters and situations to retell the tales of Japan’s past, as an expression of what the nation saw as its core values. When Mifune teamed up with director Akira Kurosawa for a series of revisionist samurai films in the ’50s and ’60s, they found receptive audiences all over the world for a take on the genre that was at once true to the spirit of chanbara and unmistakably modern.

Mifune: The Last Samurai is less a comprehensive overview of the actor’s life than it is an analysis of what that life meant. Okazaki goes in-depth on a handful of films (mostly the ones directed by Kurosawa, and only about a third of those), and covers the major details of Mifune’s personal and business relationships in the broadest strokes. His marriage, his kids, his sex scandal, his production company: all of that gets mentioned in passing. The biggest non-filmmaking part of Mifune’s bio that Okazaki digs into is his service in WWII, which was a culture shock to a man who actually grew up in China, as the son of Methodist missionaries. And the main reason the documentary spends so much time on the war is that it marked a definitive turning point for so many of the Japanese men and women who lived through it. Kurosawa, for example, spent his career trying to atone for making propaganda films in the mid-’40s. He worked to understand the nuance and contradictions within violent characters.

Mifune gave Kurosawa exactly what he was looking for in 1950’s Rashomon, playing a scoundrel whose image and demeanor changes every time somebody else tells the story of the horrific crime he may have committed in the forest. The actor’s combination of physical menace, sardonic humor, and flashes of human need and weakness made him seem much more like a real person than a character from an ancient legend. He carried that style through the next decade-plus of Kurosawa collaborations (as well as in his many films for other directors), and practically perfected the persona in 1961’s Yojimbo, a relatively light entertainment that became an international smash.

Okazaki has assembled an impressive roster of interviewees, including Mifune’s and Kurosawa’s family members, actors who worked with both men, and famous fans like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Kôji Yakusho. The style of the film, though, isn’t up to the level of its participants. Cheap-looking onscreen graphics, flat pacing, and Keanu Reeves’ monotone narration give Mifune: The Last Samurai the feel of a college film class project—like an end-of-term video essay, examining the social impact of one of world cinema’s greats.

Even if Mifune had been made for a class (which it wasn’t; Okazaki’s an accomplished professional documentary filmmaker), the professor would likely be scrawling “needs more” all over it in red ink. The minimal detail about the actor’s offscreen life isn’t the issue. What’s more frustrating is that throughout the film the narration drops tantalizing tidbits about the changes in Japan and global show business between 1945 and 1980; it would’ve been nice to hear more about the U.S. Army banning chanbara for nearly a decade, or the simultaneous international popularity of samurai pictures and Godzilla, or the shifting focus from cinema to television in the ’70s. The title The Last Samurai suggests a lot more follow-up to the documentary’s long prologue about cultural tradition and the hard lessons of WWII.

Still, none of these flaws prevents Mifune from being a pleasure to watch. The clips from Mifune’s work still amaze. The anecdotes from the sets are astonishing—such as the one about how Kurosawa had amateur archers firing real arrows at his star during the climactic scene of Throne Of Blood. Yakusho offers useful insights into Japanese acting, while Scorsese talks knowledgeably about the art of collaboration and Spielberg explains how the influence of samurai films reenergized the American Western. It’s true that for most of its running time, Mifune: The Last Samurai feels like an extended Blu-ray bonus feature. But if it were an extra appended to a box set of Kurosawa/Mifune films, that would be one more reason to buy it.