Miles Ahead finds a novel solution to the biopic problem: Just make shit up!

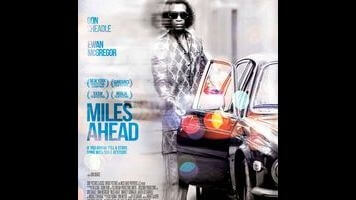

Virtually every biopic about a creative genius suffers from the same fundamental problem: Creative genius doesn’t lend itself well to dramatization. If the subject is a famous writer, for example, there’s not much excitement in showing her tapping away at a keyboard (or staring glumly into space, which is what writers do most of the time). Movies about actors and musicians are generally a bit more dynamic, since there’s an element of performance involved, but they also suffer much more from the limits of impersonation. These inherent drawbacks force biopics to largely ignore their subjects’ actual work—which is to say, the reason why anyone was interested in them in the first place—in favor of their personal lives, the details of which rarely transcend cliché. So give Don Cheadle credit for innovation, at least: His Miles Davis biopic (which he directed, co-wrote, and stars in), Miles Ahead, tackles the problem head-on… by inventing cinematic things for Davis to do when he’s not playing music, including ludicrous car chases and gunfights.

Cheadle goes so far as to set the film’s present-tense narrative sometime during the late 1970s, when Davis was essentially retired (and living on a massive retainer from his label, Columbia Records). Wandering about his New York apartment in a drug-fueled haze, he does little apart from make angry calls to radio stations playing his old work and hallucinate visions of his ex-wife, Frances (Emayatzy Corinealdi)—though there’s a single reel-to-reel tape of recent session work, which Columbia is understandably eager to acquire. That tape eventually turns into the movie’s MacGuffin after a Rolling Stone reporter named Dave Braden (Ewan McGregor) shows up at Davis’ door, saying that he’s been assigned to write the musician’s big comeback story. Braden tries to steal the tape at one point, but it instead winds up in the hands of another trumpet player’s sinister manager (Michael Stuhlbarg), who plans to… sell it on the black market? Wait several decades and sell it to Martin Shkreli? It’s not really clear.

In interviews, Cheadle has said that he intended this almost wholly fictional storyline (even Braden, the Rolling Stone writer, is made up) to capture an idea of Miles Davis, as a welcome alternative to the usual practice of merely skimming over a few biographical highlights. That’s admirable in theory, and it sort of works for a little while, though Cheadle hedges his bets with repeated flashbacks to Davis in the ’40s and ’50s—material that’s focused mostly on his tempestuous relationship with Frances, and which resembles every other biopic of a legendary musician ever made. Eventually, though, the whole stolen-tape saga—which does indeed find Davis and Braden driving frantically through the streets of New York, exchanging gunfire with bad guys—gets to be just plain silly. Avoiding monotony and cliché is one thing; turning Miles Davis’ life story into a lame buddy movie about the adventures of a monomaniacal badass and his dorky sidekick is another. At times, Miles Ahead feels like it should have been made in the ’80s, with Gregory Hines and Billy Crystal in the lead roles.

That’s a shame, because Cheadle demonstrates some talent behind the camera, especially in the film’s deliberately jagged leaps from present to past and back again (which often pivot off of violent movement in the frame). He’s also predictably charismatic as Davis, capturing the man’s raspy voice, hard stare, and infinite swagger. Had Miles Ahead taken a different unorthodox approach—focusing exclusively on Davis’ lost years, for example, without all the pseudo-gangster nonsense—Cheadle’s performance alone might well have made the result worthwhile. Instead, his onscreen electricity gets continually short-circuited by the sheer idiocies of the story in one timeframe and by the usual biopic quagmire (burnout, drug abuse, shouting matches with an abused spouse, etc.) in the other. This genre’s minefield is almost unavoidable, no matter how strenuously one tries to find a unique path through it. Cheadle did try. Give him that.