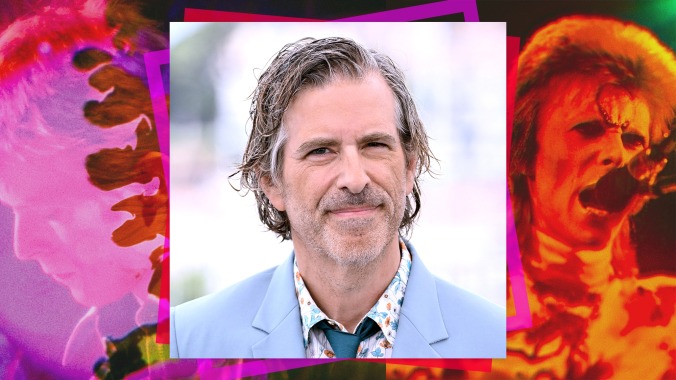

Moonage Daydream's Brett Morgen on capturing the chaos and learning the lessons of David Bowie

How the director crafted an immersive film experience and found inspiration in Disneyland's Peter Pan ride

After seven years spent digging into archives, searching through mounds of recordings, and viewing untold hours of footage, Brett Morgen managed to pull together the dazzling Moonage Daydream—the first and only film about David Bowie to be approved by the late artist’s estate. Despite its classification as a documentary, the film is hardly an educational or historical vehicle. Rather, it’s a sprawling technicolor experience that allows the viewer to fill in some of the blanks in their understanding of Bowie.

And as much as Moonage Daydream chronicles the life and musical journeys of the iconic musician, it also examines Bowie’s complicated and ever-changing philosophies as an artist and as a human. Morgen talked with The A.V. Club about the process of crafting this cinematic odyssey, its enigmatic subject, and finding inspiration in Disneyland’s Peter Pan ride.

A.V. Club: When it came to editing this film, how did you toe the line between crafting an experience that is immersive versus not wanting to overwhelm the viewer?

Brett Morgen: Well, you see, that never even crossed my mind. I like to feel sound rather than hear sound. I was thinking as I was watching the film on IMAX, “You all are in my living room right now.” My television set is supersaturated. When my own movies play on television, it’s the only time I have to go and turn the chroma down. Because my chroma is already set high. I like to see the world through rose-tinted glasses and I like to feel sound. That’s where this whole thing started, from wanting to create an immersive musical experience in IMAX before I knew I was doing David Bowie. My influences and inspirations were The 400 Blows, the Peter Pan ride at Disneyland, and Pink Floyd. Those are all very immersive experiences.

Sometimes people say a work is indulgent as a criticism. Art is indulgent. I don’t want an artist to hold back. Sometimes you need to—I think of the movie Jane. I was probably more restrained than I ever had been in honoring the subject. But with Bowie, his through line is chaos and fragmentation. That’s the story. The movie was designed sort of as a transmission from the 20th century being beamed across the galaxy to a drive-in on a different planet where sentient beings were watching one of their own. And in my mind, those people also spoke in the language of chaos and fragmentation. When I tried to pitch that it didn’t go over well. It’s hard to get money for that pitch, but that was how the film was pitched.

AVC: When you were going through all of this footage, what was the moment when you were like, “Oh, his life is defined by this level of chaos.”

BM: From the very beginning. He talked about it from the start within the recorded interviews that I came across. It was a theme and a subject. Bowie would only really talk to the press when he was out promoting an album. My favorite interviews with Bowie were during the Berlin period, when he was out promoting Low and Heroes, where he really had a window and an opportunity to talk about chaos theory. I’m listening to this interview with Bowie, and he’s talking to a bunch of journalists in a hotel in Holland. He’s saying, 300 years ago all we had to do was think about where we were getting our food from. Most people lived in an agrarian society. Right now, we’re being inundated with noise and information and ideas. When you walk down the street you’re hearing a car go by, and you’re hearing a car crash, and there’s a plane going above, and someone’s talking as they go past you. How have our brains evolved in 300 years to process all this media and information? David was creating a soundtrack for that world.

David has this line where he says, “You gotta surf the chaos.” Because when you when you throw yourself into it, it’s no longer chaotic. You know, it’s like bamboo. You sort of move with it or you’ll crack. So, David just glided through life. Watching the footage, watching the interviews, was so much more illuminating and life changing than anything I got out of my undergraduate degree. I went to school with the best: David Bowie. For two years, every day, six days a week. I was absorbing these interviews, and without going too deep on this, I had a heart attack right before I started. So I was at a point in my life where I was very receptive for some guidance.

AVC: What’s the greatest lesson that you learned from Bowie as his student?

BM: How to make every moment as adventurous as possible, and to take every moment and see it as an opportunity for some sort of an exchange or some sort of growth. Never to waste a day. He’s changed how I create. He’s changed what I’m going to do.

This film forced me to let go, it forced me to accept that there were no mistakes, just happy accidents. I had to learn how to be spontaneous. And it was not easy. It was traumatic. Watching the footage was beautiful, but I was working in a space that unfortunately, people assume is a part of a genre called biographical documentary. There’s a certain expectation and anticipation of what it is going to be. I was definitely trying to swim away from that as much as possible because to me, the cinema is my church. I don’t really go there for facts. I go there to have some sort of experience. So that’s what led me to this point in my career. If it’s in with Wikipedia, I don’t want it in my film. The audience can go and do it on their own. And I don’t—for Bowie—want to hear anybody try to explain him other than himself. Because Bowie can’t really be defined. He’s an enigma, he means something different to you and different to me. He really was the ultimate mirror.

AVC: When you say you were looking to craft this experience, where did you start? What was the piece that opened up the film for you?

BM: So I had my visual thing, right, then I had to figure out how to understand Bowie. The thing with Bowie was that he was very clear about his through-line. I accepted very early on that the film needed to have a narrative. It was never going to be 40 minutes—I couldn’t contain it within 40 minutes. It needed to have a narrative, but I didn’t want it to be overt. I didn’t want the audience to walk in and there be no mystery. I don’t understand this thing in television documentaries, where they preview what’s going to be on the show, and you see all these clips. Like, why’d you just give away the whole movie before the movie started? Because the whole idea of that stuff is not to get lost. The idea of that stuff is to always maintain some sort of orientation. This whole film was about getting lost and accepting there may no be answers. That’s the beauty of art.

The key to the film was when David said, “When I was a child, I heard Fats Domino on the radio. And I didn’t understand the word he was saying. And that’s why I found it so intriguing. It was the mystery.” I wanted the film to have that sort of mystery, but I know not all audiences want to go get lost for a couple hours in the dark. This line is very deliberately placed 20 minutes into the film. Because at 20 minutes in when he references the mystery of art, you go like, “Oh, that’s what’s going on.” If I stated it at the top, there would never be any mystery.

AVC: What’s your favorite clip you that came across during your research?

BM: You’re not expecting what I’m about to tell you. It was an interview, I think from 1987 with a Canadian journalist who was from Entertainment Tonight or the Canadian version of Entertainment Tonight. She had not done any homework on who David Bowie was. She sits down and he sits down and I’m like, “This is not gonna go well.” It was clear she had no idea who he was at the time. And David starts talking to her about books. “Oh, have you read the new… ? It’s absolutely brilliant.” And she was totally freaked out for someone, and then David says, “So tell me what you’ve been reading.” And that was the moment I was like, “Every moment is an opportunity for an exchange.” If you’re there, and I’m here, let’s make something happen.

AVC: What is the biggest message you want viewers to take away when they when they leave the theater?

BM: I would say that the message is: How should I go about my day tomorrow? Am I taking advantage of the limited amount of time that I have left? That’s the personal one. Then the bigger one is: What a remarkable life. That’s how you do it. This chap knew how to do and he did as well if not better than almost anyone.

AVC: As a Bowie fanboy, what’s your favorite song and favorite era?

BM: 1995 to 1997 is my favorite era, and my favorite song of the day, or the hour, because it changes moment to moment, let’s go with “Cygnet Committee.”