More than 70 years later, Brief Encounter remains intensely poignant

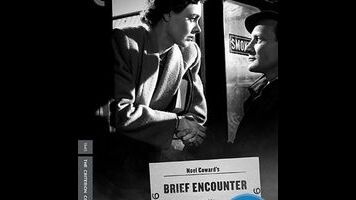

For all the romances the movies have given us, there are precious few that show two people gradually falling in love. Contemporary rom-coms generally engineer a movie-long feud that builds to a climactic smooch; Nicholas Sparks-style weepies go for insta-passion shorthand, the better to clear the way for whatever ludicrous tragedy its lovers have in store. And that makes sense, really, as the realistic alternative—with ardent feelings accumulating bit by bit over time, in a context devoid of manufactured conflict—seems like it would be too politely dull to endure. All the same, that perfectly describes Brief Encounter, David Lean’s 1945 masterpiece of British restraint and repression, which Criterion has at long last upgraded to a stand-alone Blu-ray title. (It had previously been available on Blu only as part of the David Lean Directs Noël Coward box set.) The experience of involuntarily embracing someone who threatens to destroy your life has never been more exquisitely realized, in all its glory and misery.

Adapted from Coward’s one-act play Still Life, Brief Encounter employs a structural gambit that will look mighty familiar to anyone who saw Todd Haynes’ Carol, which lifts it wholesale. At a railway station, a man and a woman sit talking, too quietly for us to hear; a casual acquaintance of the woman then sits down uninvited and proceeds to babble incessantly, until the man is forced to say a placid goodbye and catch his train. As in Carol, the scene will be revisited, and completely recontextualized, near the end of the film, when we learn what was being said prior to the sudden interruption. In between, the woman, whose name is Laura (Celia Johnson), fills in the backstory, narrating events—solely in her imagination, thereby increasing the pathos tenfold—to her loving husband (Cyril Raymond). She tells him of her chance encounter, during one of her weekly shopping trips to the city, with a doctor named Alec (Trevor Howard), who helps her remove a bit of soot from her eye. Their subsequent once-a-week meetings grow more and more intimate, even as both parties feign propriety, until they end up in a borrowed flat.

The sheer helplessness Laura and Alec feel, as they lay the tracks toward that rendezvous, is what makes Brief Encounter so intensely poignant. These are middle-aged, respectable people, for whom infidelity feels like a mortal sin; the more they grow to love each other, the more they hate themselves. Coward’s play acknowledges this while simultaneously allowing them their giddiness in each other’s company, and the movie expands his vision to include Laura’s husband, who at one point blithely perceives Alec as a tedious imposition rather than as a threat (but who also, the tearjerking finale suggests, may understand more of her heart than he lets on). Lean hadn’t yet graduated to the epics for which he’s now famous, and he shoots most of Brief Encounter as simply and cleanly as possible, which lends uncommon force to his very occasional formal flourishes—most notably, a disorienting tilt of the camera that visually represents one character’s momentary descent into suicidal madness. (Lean also abruptly cuts from a close-up to a wide shot when Laura and Alec first kiss, which is both the opposite of what you’d expect and utterly perfect.) What’s more, the movie’s repeated use of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto No. 2” has Laura twice wandering the streets alone to what now sounds like the bridge to Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself.” Only a genius could anticipate future pop-music appropriation so ideally.