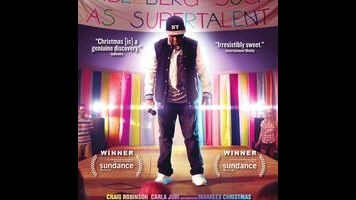

“A unique perspective.” That’s how single dad Curtis (Craig Robinson) spins the tough move he’s put his 13-year-old son through. As fatherly silver linings go, it’s right up there with “builds character.” Curtis, you see, hasn’t just dragged Morris (newcomer Markees Christmas) across the country. He’s relocated his boy from the Bronx all the way to Heidelberg, Germany, where he’s accepted a position coaching soccer. Morris, who aspires to hip-hop superstardom, is a shy black kid in an overwhelmingly white city. He can take solace only in the promise of autobiographical pay dirt—that special something to distinguish his life experiences from those of his fellow budding MCs. Morris From America reaps the same benefit. How many coming-of-age stories, after all, focus on an African-American expat in a European city?

It’s a lonely summer for Morris, whose only real friend, beyond his gregarious pops, is the twentysomething tutor (Carla Juri) slowly teaching him German. The language barrier isn’t his only social setback. Weight also makes Morris a target, though his skin color is all many can see: The other kids call him Kobe (a nickname both racist and sarcastic, given that he expresses no interest in playing basketball with them), while the head counselor at the youth center regards him with instinctive distrust. This daily obstacle, hardly unique to Heidelberg, gives Morris From America an extra charge of resonance. Without compromising its low-key charm, the film acknowledges the stereotypes black kids have to navigate around even in “enlightened” society.

Race certainly plays a role in the lopsided friendship Morris eventually develops with blond beauty Katrin (Lina Keller), instant object of his teenage affection. Two years older than her admirer, Katrin is way, way out of Morris’ league (like the dream girl of spiritual cousin Sing Street, she has a man-sized, motorcycle-riding boyfriend). But she entertains his infatuation anyway—partially because Morris presents an “exotic” alternative to the horny idiots that circle her like flies, but mostly because she’s flattered by the attention and wants to freak out her conservative mother. Anyone who’s ever willfully allowed themselves to be led on by a crush who plainly does not reciprocate their feelings will nod with wistful recognition. Teenage boys past and current may be less eager to admit that they see themselves in the scene of Morris, ready to burst with frustration, finding a creative new use for his pillow.

There’s nothing flashy about Christmas’ turn, but that’s in keeping with the conception of Morris, a self-conscious young man gradually working up the courage to emerge from his shell. The actor seems to come alive most opposite Robinson, who’s punched up the margins of lesser movies with his deadpan timing. Here, the Office alum delivers the single warmest performance of his career, playing a widowed father trying to negotiate that line between respecting his son’s autonomy and laying down the parental law. Curtis is struggling with his own, adult strain of homesickness and loneliness. He also has a rich, complicated value system: Stumbling upon Morris’ fledgling stabs at gangsta rap, Curtis is offended not by the explicitness of the lyrics, but by their phoniness. He wants his kid to write what he knows, to find an authentic voice to accompany his growing style and confidence.

Speaking of style and confidence, Morris From America constitutes a huge leap forward in both for writer-director Chad Hartigan, whose last feature, This Is Martin Bonner, was about as minimal as American cinema gets. With Morris, the filmmaker replaces the stripped-down aesthetic of that indie breakthrough with a new bag of tricks—zooms, Steadicam shots, irises, fantasy sequences, slow-motion, fast-motion—while never creating the impression that he’s just showing off. (The best of these flourishes, like a fountain exploding behind Morris and Katrin as the two share a pair of earbuds, seem designed to put viewers right inside the title character’s head.) But Morris is also much more conventional than Martin; though Hartigan is essentially inverting his own immigrant story—he moved to America from Cyprus with his father as a child—the film could have used more of the distinctive ache of memoir.

Still, Hartigan manages to subvert some of the moldy clichés of underdog cinema, blowing past an expected triumph and then undercutting the replacement one with the stark reality of Morris’ (mostly hypothetical) love life. Ultimately, familiarity can’t entirely diminish the pleasures of a film this genuinely sweet, from the humor and heart Christmas and Robinson conjure in their scenes together to the insight into alienated youth that Hartigan wrings from some very common tropes. And, of course, the fish-out-of-water angle helps. Because if you’re going to tell a coming-of-age story about a kid with a tough-love father, a dead mother, and a hopeless crush on the coolest girl in town, you’re going to need all the unique perspective you can muster.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)