Roubaix (population: 95,000) is a small working-class city on the northern edge of France, located just minutes from the Belgian border. It is the former center of a textile industry, the finish line of the storied Paris-Roubaix bicycle classic, and the hometown of the gifted French writer-director Arnaud Desplechin. Desplechin’s latest, My Golden Days, represents a three-point return: to Roubaix, previously the setting of his family ensemble piece A Christmas Tale; to the rap and college rock 1980s of his youth; and to the archetypal characters of what’s still one of his best films, My Sex Life… Or How I Got Into An Argument, the freeform, three-hour hip relationship drama to end all hip relationship dramas. Desplechin tackles drama with wildly confident eclecticism, sometimes even besting Martin Scorsese in pure movie-mad feverishness: iris shots, radically different camera styles, unexpected musical and literary quotations, theatrical flourishes, scenes broken up in collage. His take on the coming-of-age film, however, is one of those cases where the framing devices and framing stories are more compelling than what’s being framed.

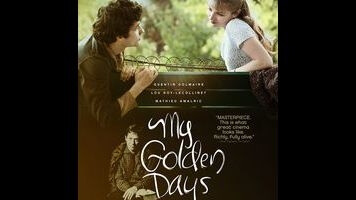

In a typically offbeat move, Desplechin begins My Golden Days—a movie that’s mostly about horny teenagers in ’80s Roubaix—in Tajikistan, with a slowed-down arrangement of the theme from Shoot The Piano Player playing under dialogue in Russian. Paul Dedalus (Mathieu Amalric, Desplechin’s charmingly fidgety regular leading man) is an ethnologist returning to France after nearly a decade abroad; he isn’t exactly the same Paul Dedalus that Amalric played in My Sex Life.., though he has the same pensive and neurotic qualities. Stopped at the airport, Paul is taken into a grayish room to be interrogated by a nameless agent (André Dussollier) who tells him that there’s a man with his exact name, birthplace, and birth date living in Australia. This question folds out into an unconventional Cold War thriller, and the story of how the teenage Paul (Quentin Dolmaire) helped Soviet Jews during a school trip to Minsk, but not before an extended foray deeper into his childhood, and his bad memories of his mentally ill mother and his fond memories of his great aunt.

Then, after a few more detours, My Golden Days settles into its third and central chapter, titled “Esther,” after Paul’s insecure first love. Again, this isn’t exactly the same Esther who was Paul’s girlfriend in My Sex Life…, though she’s played by Lou Roy-Lecollinet, who bears a strong resemblance to Emmanuelle Devos, who played the character in the earlier film. Toning down his dizzying style just a notch, Desplechin evokes small-town teenage life in the pre-cell phone age, set to a soundtrack packed with everything from jangly twee to classic hip-hop to first-wave ska. But though Dolmaire and Roy-Lecollinet, both first-timers, are good in their roles, their characters lack the neuroticism and anxiety needed to match Desplechin’s manic, omnivorous style. The director’s longstanding preoccupations are all here: ethnography, the Cold War, therapy (parodied in Paul’s interrogation), classical literature. But in lieu of his usually unpredictable narratives, there is a more or less traditional coming-of-age piece, laced with pity and nostalgia, in which undergrad Paul, studying in his first year in Paris, falls in love with the high-school-age Esther over weekend visits home.

Desplechin loves his Shakespeare, and his best films, like My Sex Life… and Kings & Queen, seem to be aiming for the Bard’s range, following countless interesting characters from farce to naturalism with a creative vocabulary that tries to create an audiovisual equivalent to Shakespeare’s inventive and imaginative language. But despite some striking uses of direct-to-camera address (a Desplechin staple), My Golden Days’ undercurrents of regret remain just that, never breaking in a gush over the colorful surface of the film. Still, it’s a treat to watch, covered in eccentric strokes and oddball details that seem too specific not to be extremely personal. What comes effortlessly to the film—sensuality, the specifics of place and era, droll humor, the atmosphere of teenage social life—leaves more of an impression than the elegy for things past it tries to squeeze out of Paul’s point-of-view.