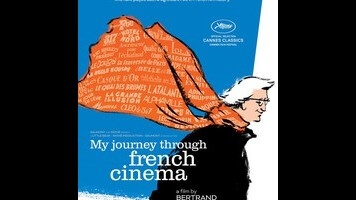

“At the Pathé Journal, I saw a guy next to me open a can of peas, heat it up, and eat it,” recalls Bertrand Tavernier with a survivor’s perverse pride as he describes the widely mythologized Paris movie houses of the 1950s in My Journey Through French Cinema, his smart and gregarious personal tour through the first four or so decades of French sound film. Tavernier himself is one of the most skillful and, in this country, underappreciated French writer-directors of the generation that came after the revolutionary New Wave. In America, he’s probably best known for the Jim Thompson adaptation Coup De Torchon, a film that showcases his dark wit, though his historical dramas (including Captain Conan, Let Joy Reign Supreme, and The Judge And The Assassin) really belong in a class of their own. The best guides to film history are generally opinionated and very personal, and that’s what My Journey Through French Cinema offers to both eager-to-learn newcomers—who might be turned off by the running time, but shouldn’t be—and self-appointed experts: a selective, eccentric survey of the richest periods of French moviemaking and, by extension, film in general. Less wide-ranging than A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (presumably an inspiration), it stretches out to 195 minutes as casually as a weekend lunch, never feigning completism.

Tavernier is a tall, hunched man in his mid-70s with windblown white hair, a lazy eye, and a hearty laugh—something of a character, like most great directors. However, he remains offscreen through much of My Journey Through French Cinema, preferring to narrate hundreds of carefully chosen film clips. This isn’t the first time he’s done something like this; his sadly out-of-print The Lumiere Brothers’ First Films remains the best introduction to thinking of the earliest of the early filmmakers as sophisticated artists. But though this at times makes My Journey too pragmatic for its own good, what sets it apart is Tavernier’s interest in craft, which has always distinguished him from most of his filmmaking peers. A former film critic who came up during the ’50s and ’60s heyday of the ekphrastic auteur cult, he nonetheless avoids the Great Director view of film history. There are long sections devoted to the music of Maurice Jaubert, who composed the scores for such ’30s classics as L’Atalante and Le Jour Se Leve; the legendary production designer Alexandre Trauner’s work on the latter film; and the artistry of the obscure This Man Is Dangerous, one of the first movies to feature the pockmarked American expat Eddie Constantine as Lemmy Caution, the ’50s and early ’60s B-movie hero resurrected as a futuristic gumshoe in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville.

Even when he discusses the big names, it’s from the perspective of someone with both appreciation for the minutiae of movie craft and a firsthand knowledge of the personalities involved, veering a sharp left away from the obvious. In discussing Jean-Pierre Melville, the Gallic noir master whose sense of laconic cool has influenced generations of genre directors, Tavernier instead focuses on the maniacal precision with which Melville framed reverse shots in dialogue scenes and on the frequent recycling of sets and locations (many of them either in or close to Melville’s production office), which betrayed his deeply personal relationship to his gloomy crime and suspense stories. Melville, whom Tavernier first got to know in his last teens, emerges as one of My Journey Through French Cinema’s most memorable characters—an insomniac who would drive the young Tavernier to the same night spots visited by the world-weary cops and thieves in his films, highly opinionated on the merits of other filmmakers and prone to temper tantrums on set.

One of the more revealing archival clips included here is an audio-only outtake of a shouting match between Melville and actor Jean-Paul Belmondo on the set of 1963’s L’Aîné Des Ferchaux, their third and last collaboration; later, Tavernier reveals that Melville and Lino Ventura, the star of one of his masterpieces, Army Of Shadows, would only talk to each other through assistants, even if they were in the same room. But for all the juicy tidbits that emerge from Tavernier’s memories—stories about audiences booing François Truffaut’s Shoot The Piano Player or about how Godard would only extend set visit invitations to critics who viciously panned his films—My Journey Through French Cinema is most useful as work of criticism. In a late section devoted to Godard, for whom Tavernier worked as a publicist in the early-to-mid-’60s, he zeroes in on how the New Wave icon edited the original scores for his most famous movies, splicing in pauses of complete silence between orchestrated phrases. This focus on minutiae doesn’t paint a complete picture, nor is it meant to. But it underlines a point too rarely made: Every film is an accumulation of things the average person wouldn’t notice. If there’s a real educational function to criticism, it isn’t to inform, but to teach an audience how to look.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.