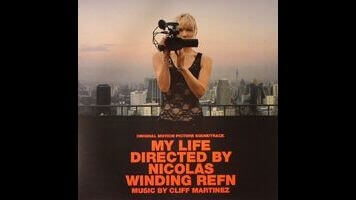

My Life Directed By Nicolas Winding Refn is a familiar account of an unusual film

My Life Directed By Nicolas Winding Refn, Liv Corfixen’s behind-the-scenes look at the production of Only God Forgives, has a clear precedent in Hearts Of Darkness, Eleanor Coppola’s behind-the-scenes look at the production of Apocalypse Now. Both films depict a director fresh off of a critical and commercial success—Drive in Refn’s case, The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II in Francis Ford Coppola’s—by making a “difficult” film in a foreign country. Both have the unprecedented access and personal touch that comes with being shot by the director’s wife. But there are two key differences: First, Corfixen claims sole directorial credit here (Coppola shared that title with two other people for Hearts Of Darkness), so her perspective comes through more clearly. Secondly, despite the clear mental toll making Only God Forgives takes on Refn and his family, it’s not a disastrous shoot per se, and certainly not a fiasco on the level of Apocalypse Now.

Bookended with tarot readings from family friend Alejandro Jodorowsky, My Life Directed By Nicolas Winding Refn follows a straightforward narrative arc from Only God Forgives’ pre-production all the way to its premiere at Cannes. Along the way, Corfixen documents her husband’s creative process as well as his mental state, which comes in two basic modes: confidently inspired and nervously despondent. Refn spends much of the film fretting about the expectation that he’s going to make Drive 2, first boldly rejecting it on artistic principle, then fearfully wondering if he can ever make a movie that successful again. (All neurosis aside, Refn does seem to have a sense that Only God Forgives won’t be as successful as Drive, saying from the very beginning that it isn’t going to be a “commercial” film.) My Life Directed By Nicolas Winding Refn is most compelling when Corfixen captures Refn in a private moment on the set, watching him try to keep his composure in the face of crippling anxiety so the crew doesn’t lose faith in his leadership.

The film also gets a lot of mileage out of juxtaposing the operatic ultra-violence inside Refn’s head—“I’ll kill you tomorrow and disembowel you the following day,” he deadpans to actress Kristin Scott Thomas—with his mundane family-man personal life. We learn things about him, like that his nickname around the house is “Jang” and that he considers rain a bad omen. Even the presence of big-time movie star Ryan Gosling feels ordinary; in one scene, Refn is grandiosely describing how violence is like sex (the longer the buildup, the better the climax), and Gosling, ever the movie star, winks at the camera and asks, “You get all that?” Only when they interact with the outside world do we get a sense of how important these men really are.

But Corfixen is not overly worshipful of her husband. Sometimes he appears downright silly, a big kid wrapped in a blanket playing artistic genius. The film’s most interesting undercurrent, one that might have been developed more fully with an additional 10 minutes or so of footage, is the question of what Refn’s career as a director (and the oversize ego that comes with it) means for the people closest to him. Corfixen is not afraid to take Refn to task for his more arrogant tendencies; one of the most compelling moments in the entire film is in the title sequence, where Refn instructs Corfixen on the best place to stand to get a good shot while she interviews him. Even in this intimate setting, he’s a director, and she’s the directed. If only the rest of the film was this insightful.