Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie: The oral history

The entertainment landscape of the 1990s was compartmentalized: Film was meant to be seen on the big screen, television was for home viewing, and the two rarely commingled. This seems archaic today, when the lines between pop culture media are blurred daily, but it was once a fact of life. Only TV shows with the most dedicated cults—Star Trek, Twin Peaks, The X-Files, The Kids In The Hall—could even attempt a leap into cinema.

Twenty-five years ago, Mystery Science Theater 3000 became one of those shows. Boosted by a passionate, dedicated fan base and critical acclaim, this scrappy comedy from the Twin Cities managed to beat the odds when Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie opened across America on April 19, 1996. All these years later, the movie is still a favorite among many MST3K fans and has garnered a broader, albeit still small, following. But its journey to the big screen was a prolonged and difficult one for those involved. Having previously operated outside of the traditional Hollywood machinery, MST3K’s talented cast and crew struggled to navigate the creative compromises and logistical challenges that came with being financed by a major studio like Universal. Though crowdfunding is set to resurrect the show once again via an ongoing Kickstarter campaign, the infrastructure to support that kind of independence did not exist in 1996.

Looking beyond the narrative of creative difficulties and studio interference, the story of Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie is also one of resilience, creativity, dedication, and, of course, humor. To celebrate the film’s 25th anniversary, several of those involved in the creation of this beloved TV-show-turned-movie were interviewed—Michael J. Nelson, Kevin Murphy, Trace Beaulieu, Jim Mallon, Bridget Nelson, Mary Jo Pehl, Frank Conniff, and Joel Hodgson—and current host Jonah Ray also discussed the film’s legacy and influence. All interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity; credits refer to work done on Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie unless otherwise noted.

The notion of making a film adaptation of MST3K was discussed early in the show’s run. Creator Joel Hodgson was heavily involved in initial treatments and negotiations for the film, but how to adapt and fund the project became a central point of contention. And once a deal was struck between Universal Studios and the show’s production company, Best Brains Inc., the MST3K crew then had to find the right film in the studio’s vault to become the centerpiece of their movie.

Kevin Murphy (“Tom Servo”/Writer/Producer): We had been batting around the idea since about the time that we knew the show had a little life to it and was going to be around for a little while. Frankly, I think we were all amazed [during] the first three seasons that we kept getting renewed. I think we all had it in our heads that this would make a fun movie, at one time or another.

Mary Jo Pehl (Writer): I know that Jim Mallon had been wanting to do it for years. So it had been talked about on and off. I think at one point there might have been a treatment done. I know it was lobbied back and forth for quite some time.

Jim Mallon (Writer/Producer/Director): The genesis of the movie was the observation, [which] I believe I made in the writing room, that the more people that are in the room watching Mystery Science with you, the more fun it is. Partly that is because the show was unabashed about obscure references. So for example, there was one movie that was horribly made and had scenes of a stock car race that were all yellowed. We made the comment “They’re shooting tungsten.” Well, that’s a comment you’re not going to know unless you know a lot about film stocks and how film stocks behave under certain lighting conditions. If you shoot tungsten film outside, the film goes yellow. To the one cinematographer watching the show, it’s a custom joke for him. No one else is going to understand. However, if you get a room full of people, there’s more odds that obscure references will be decoded. So it was a simple leap: “Where are there a lot of people together in a room watching something? Maybe we could do this as a movie?”

Bridget Nelson (Writer): It did seem extremely exciting, but also like, “Oh, yeah, this should be a movie. Of course.” It really was a cool thing, but it felt like a natural thing. The writing [on the show] was so good and we’ve got this growing fan base and we know what we’re doing. It felt like a natural next step.

Joel Hodgson (Creator, Mystery Science Theater 3000/Host, 1988-1993): We were reacting to Star Trek: The Next Generation jumping to feature films. Immediately after that, we started talking about doing the same thing. And instead of making 22 funny feature-length episodes, we were going to make one really funny feature-length feature.

Trace Beaulieu (“Dr. Clayton Forrester”/“Crow T. Robot”/Writer/Producer): Sometime early on, when Joel was still on the show, we started to kick around the idea. I think Joel had a contact at Paramount, and we pitched it there. We tried to find a movie that Paramount had a license for. So it even got that far. I think we looked at When Worlds Collide, which would have been terrific but almost too good. But those negotiations fell apart.

Joel Hodgson: Casey Silver was the guy I remember us talking to [at Universal]. We went to L.A. and met with him. We worked really hard on breaking a story for the feature. It was going to be set at a mad scientist convention in Las Vegas. I remember it was a demo. The idea was The Mads had a booth and they were like, “Hey, we got this guy up in space and we make him watch bad movies.” That was kind of the premise. I remember some really fun ideas we had, like a casino named Dante’s Inferno that was on fire. That was kind of the setting. Then from there, you just kind of had Mystery Science Theater. It was us trying to make the show more cinematic.

Then the ending was something with a time machine. They turn it on and Hitler darts out of it, and runs into the crowd. That was really funny. And the big ending was really cool, because we were going to crash the Satellite Of Love. So the big dramatic ending was the Satellite Of Love crashing into the Earth’s atmosphere, and it was going to crash into Vegas. Then somehow we had kaiju that were running in the desert, like a Hail Mary pass in football, and they caught it. They caught the Satellite Of Love and everything was okay. That was us treating it like, “You can’t change the Satellite Of Love too much but we can do a bigger opening and closing, the interstitials with The Mads.”

The problem that I had, though, was how do you translate the aesthetic of the TV show to a feature film? I felt like that was the biggest thing to tackle. I don’t know if you know this, but that’s what broke up the band. The reason I left the show was because of the feature. There were creative differences.

Frank Conniff (“TV’s Frank”/Writer, Mystery Science Theater 3000, 1990-1994/Uncredited writer, Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie): Joel was definitely involved with the movie, but not necessarily the movie that ended up getting made. I think early on the plan was that Joel and Jim Mallon were going to co-direct the movie, but obviously Joel left the show and that never happened. But I remember that being the plan at some point.

Michael J. Nelson (“Mike Nelson”/Writer/Producer): As I recall, it started with crazy, large ideas about what it would be—a Muppets-style movie with a big budget and everything. Then it just kind of bounced around, studio to studio, until it landed where it did. But there was always interest in it. I just recall it being a very up-and-down kind of thing. Like, “Hey, there’s somebody interested! No, now it’s just stalled out.” I think it was a fairly long lead-up time to it.

Frank Conniff: I was part of a lot of brainstorming sessions about the movie, like different versions of the movie that never got made. We came up with a whole storyline at one point [where] Joel and the bots and the mad scientists were going to be a bigger part of it than the movie riffing. Eventually we figured out that people really wanted the movie riffing. I think at first there was a tendency to say, “Well, this has got to be different from the TV show. It’ll be more the backstory of everything.” And we had a lot of brainstorming about that. I think we came up with fun stuff. I think it was a mutual decision of the studio and Best Brains [to say], “It’s going to be mostly the movie riffing but with host segments, just like the TV show.” It ended up being like an episode of the TV show, but with a bigger budget and interference from people.

Jim Mallon: So when we decided we wanted to pursue a movie, one of the most difficult things to figure out was, “Should this be done independently? Should we try to raise the money ourselves and shoot the movie? Or should we try to get into a studio where it’s all set up and they write you a check?”

Trace Beaulieu: I was talking to Kevin [Murphy] a couple months ago about how it was proposed by our attorney at that time that we could invite the fans to help us make the movie. Essentially doing what people are doing now—crowdfunding. And we went, “Huh? What? Can that be done?” It was a radical idea. It would have been cool. We could have done it our way, like an indie band.

[Universal] said to us, “It would be a heck of a lot easier if you took a film that we already owned.”

Jim Mallon: The history of the show was just this scrappy little show that came out of nowhere. It kind of made it by hook or by crook. But the problem was we weren’t really a scrappy little show anymore. We were an enterprise that was supporting about 20 peoples’ livings. We couldn’t take six months off to pursue money independently and make the film independently, because then we would have lost all these employees and writers and talent. There would have been no way to support them. So that really kind of pushed us towards getting involved with a studio.

But that was a very difficult endeavor. We were kind of hillbillies up in the north making fun of the product that Hollywood kicks out. And now we’re connecting with a major player, Universal Studios. And there’s a lot of curious and challenging and, frankly, joyless things that came out of that experience. But it gave us a budget [and] it gave us a pristine cut of [This Island Earth]. But, again, it was complicated because they were trying to do the film, what they called, “under the radar.” I think the initial budget was $2 million, which was chump change for those guys.

By the way, one of the reasons we were at Universal, and I’m trying to remember the gentlemen’s name, [was because] the Universal lawyer was a huge fan of Mystery Science. He was the one that was skating this, truly, “under the radar” to get it made. That was part of the magic of Mystery Science. Wherever we went around the country, we’d find one or two passionate people inside the various institutions that we were visiting. There were a million issues, and he would help us negotiate through that labyrinth.

[Universal] said to us, “It would be a heck of a lot easier if you took a film that we already owned.” And I don’t know if we would have done This Island Earth if we had a chance to do the whole range of films available.

Michael J. Nelson: That was the really fun part of it, actually. We sort of narrowed it down based on the catalog they sent us. It was a pretty narrow list.

Trace Beaulieu: We wanted something in color, we wanted something that was riffable. That narrowed the field dramatically. It wasn’t like, “Let’s go to Universal because they’ve got This Island Earth! Boy, wouldn’t it be great to kick that in the balls!” We found This Island Earth at Universal after a search through tons and tons of stuff—everything that was color and in their library that we could use. We watched so many TV movies and TV series to find [something]. We looked at a lot of Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Even old Night Gallery episodes.

It was kind of cool because we were in a screening room on the Universal lot and they had to play all of these things for us. There was no sending a file or watching it on disc. We had to go and look at this stuff. There was a guy in this little booth and we’d say, “Okay, run the next one.” We felt like big deal movie guys.

Michael J. Nelson: It was one of my favorite moments, picking up the phone and calling [the projectionist]: “Hank, could you run back that reel of film?” “Yes, Mr. Nelson.”

Kevin Murphy: [This Island Earth] was one that just stuck out because it seemed to check off as many boxes as possible. It’s a very earnest film, and yet when you look at its earnestness, it makes you laugh because of how silly it is. You know, these aliens with giant foreheads running around in tweed jackets, and no one seems to suspect there’s anything wrong with the fact that their foreheads are 3 feet high and everyone has white hair. Things like that. And Cal, the big lantern-jawed hero, comes off as trying to be heroic but is sort of dopey. Faith Domergue is just sweet and fun to have in the movie. [And with] Russell Johnson, we get the professor from Gilligan’s Island. And we got the monster, who we named Scrotor for obvious reasons. It rambles along. It’s goofy but earnest, and never tries to be tongue in cheek. And that kind of material is always really good for us.

Michael J. Nelson: [This Island Earth] was just the one that looked the best onscreen. It’s good enough. It’s bad enough. It’s funny enough. It’s got stars.

Mary Jo Pehl: I think we had enough to go on because of the alien’s giant heads, the interocitor, and the whole 1950s dynamic of the strapping white guy who is going to fix everything.

Michael J. Nelson: The thing that surprised us was how many in the media, who I think had affection for the movie, said, “Do you worry that this is the first great movie you’ve ever done?” I remember the first time someone gave me the questions, I was like, “Great? That’s a little bit of a stretch, isn’t it?” But then we said to people, “Have you seen it since you were a kid?” And everyone would go, “No, I haven’t.”

Jim Mallon: It wasn’t the optimum Mystery Science movie. We went through their goofy movie library and it was the best of the bad that they had. It’s a classic in many ways, right? There’s quite a difference between [This Island Earth] and, let’s say, Manos: The Hands Of Fate, which was made by a fertilizer salesman in Texas. Compare that to a movie that is made by one of the top three studios in Hollywood. It’s a different animal.

Trace Beaulieu: It still exists in its original form, we didn’t cut up the negative. We didn’t carve a mustache into the Mona Lisa.

Now with studio backing and a film secured, the MST3K crew began the process of writing the screenplay for their movie. Though they approached the early versions of the screenplay the same way they would an episode, they were afforded more time to write the script and a unique opportunity to test it. At their first fan convention, ConventioCon ExpoFest-A-Ramain in 1994, they performed a live show that riffed This Island Earth.

Jim Mallon: I think for the TV show, we did an initial run-through and then editors would edit that down. We would record the show, watch it, and then do what we called “adds and deletes.” That’s it for the TV show. Then it’s on to the next one because we were cranking them out at a huge pace. But for the movie, we got to spend the better part of a month working on the script.

Mike Nelson: It just took so long. That’s the thing I remember about it. We could kick out a show, in the early days, in a week. I think it ended up being, like, two weeks at the end, because we were afforded a little more time and wanted to put a little more care [into it]. So the length of it was frustrating for me, I have to admit.

Frank Conniff: At that point, I was still with the show, and I was still involved with everything happening. So I was involved with writing riffs for This Island Earth. I know that some of my jokes still survive [in the film]. If someone wants to dispute me about this, I won’t argue with them, but my memory is that when the professor from Gilligan’s Island comes in, when they first see him walk into his room, and the line is “What’s this, ‘And the rest’ shit?” that was my line. For the movie, I think it was, “What is this ‘And the rest’ crap.”

Bridget Nelson: I just remember laughing in the writing room, like we always would. My absolute favorite line, which is a favorite line with my whole family, is [when they’re] in the spaceship and Mike says, “You’re being kidnapped by The Light FM.” I love that one.

Michael J. Nelson: I think that the meat of it, the jokes over the movie, went about as smoothly as possible. We did our usual thing: writing it first and then field-testing it with ourselves. Then it was us saying, “You know, we can make this joke better.” So it was just a typical script. The [host segments] around it was 99.8% of the work.

Kevin Murphy: We knew we didn’t have commercial breaks, so we had to come up with some sort of device that allowed us to pull out of the theater. For the final product, it was Dr. Forrester having some problems, or there was a meteor shower hitting the satellite, or the Hubble [Space Telescope] is broken. We just made up excuses to get them out of the theater.

Michael J. Nelson: There was one script, I recall, that we really thought about using a lot of music in. We were just kind of coming up with that idea. We didn’t have anything finished but we just had this idea: “Man, puppets and music just work so well together.” And then the studio came in, without us even saying anything, and said, “The one thing we don’t want to do is to have any music whatsoever. We just screened a film that had music in it and the audiences hated it so much.” We’re quietly tucking that draft behind our back: “Oh, yeah. No, of course. Music? What? We hate it.”

Frank Conniff: Before it was a movie, we did it as a live show. We riffed it in a live performance at our—I think it was the first of two—conventions that we had in Minneapolis. I believe we did it at the Uptown Theatre in Minneapolis. It was one of only two live shows we ever did while we were still doing the show.

Jim Mallon: We had 1,300 people from around the country gather in Minneapolis and we rented the Uptown movie theater, and we did a live version of a show there. And it killed. It was just over-the-top. That gave it a lot of momentum.

Michael J. Nelson: Obviously, that was the first time that we ever had that direct feedback. A number of us had done stand-up comedy, so you have that sense the audience will either stab you or laugh. So doing it in front of a live audience was great. It was like, “Oh, most of the jokes are hitting and here’s how we need to sort of pace it.” I just remember that being just exhilarating in terms of “This is how it works. This is how people actually receive it.” That was a lot of fun. It was a preview audience. The stunning thing was I was sitting backstage when the theme song started up and the crowd started singing every word and stomping like it was a sporting event, like they were soccer hooligans.

Kevin Murphy: I think doing it live was sort of a proof of concept for us. We wanted to show the powers that be, including our agents and the studio, that we have no problem filling a theater and making people laugh nonstop for 90 minutes or so. And it worked because it was great fun. It was a great movie for us. The live show that we did was just fantastic. We thought, “If we can carry that feeling into a movie theater, man, we’ve got something.” It showed that what we’ve been doing on TV was 10 times as much fun when you see it in an audience full of people.

Frank Conniff: Our fans are so enthusiastic and supportive. That was a very early instance of us being able to see all that up close. Since then we’ve all experienced it a million times at other conventions and our own live shows, just being face to face with the people who are fans of the show. But I think that was really the first time we really got to experience that, and it was great.

After shaping an early draft of the script and a successful test run in front of an audience, the MST3K crew seemed like they were gliding toward their big-screen debut. But this positive momentum was stopped in its tracks when notes from the studio came pouring in. After years of autonomy in the Twin Cities, MST3K was quickly becoming ensnared in the gears of the Hollywood machine. For the first time, they had to figure out how to keep their vision pure while performing a delicate dance with their backers at Universal.

Frank Conniff: If you had a tape of the live show and compared that with the movie, I’m sure there’d be a lot of different riffs. Because from what I’ve heard, they had to take a lot of notes from the studio and change jokes. They couldn’t do jokes that were too obscure. When we did the TV show, we just did whatever jokes we wanted to do.

Mary Jo Pehl: We were kind of working in isolation [on the TV show]. We didn’t have a lot of oversight from Comedy Central—a little bit more with the Sci-Fi Channel. We were really working to make each other laugh because we knew we had shared sensibilities. But we all brought something different to the table as well. I think in our writing room, we were really working to make it a better show. We all had egos but it was all about making a better show.

Frank Conniff: Mystery Science Theater 3000 was the first show ever that I worked on, my first TV show. I didn’t realize until after I left the show how great what we had with Comedy Central was, how ideal that situation was. We were able to make this show and do exactly the show we wanted to do with no studio notes, no executive interference. And then after that I moved to L.A. and worked on sitcoms. I found out how rare that is. I don’t know if while it was happening we really appreciated how good we had it.

Bridget Nelson: I remember the first time we did a run-through of the script and the executives were there. This is before we figured out that we should have just been running roughshod over them. Before we realized, “Why are we listening to them about comedy?” We should have just done our own thing. But we were nervous that they were there—at least I was. We sit down, and I get a call from my niece, who was babysitting [Mike and I’s son] August, that the fire alarm at the house had gone off. So Mike had to drive back home, get it to shut up, and then come back. So already, we were not presenting the most hip L.A. vibe that you could. He had to get in my Toyota Camry and drive home.

Jim Mallon: It’s just this weird interplay of bringing a show that’s about making fun of Hollywood into Hollywood to be made. It’s just a weird energy coming together.

People who aren’t comics are just on the outside. It’s just like a guild. You’ve been up onstage, you’ve driven to a North Dakota sports bar on a Friday night and almost got killed. You’re part of a team, you’re a Spartan.

Trace Beaulieu: Comedy is personal and you either like it or you don’t. We would often trust what we had done. It was a different experience dealing with the studio, going line by line with a thing that doesn’t need that kind of dissecting. They had their job and we had ours. Their joke telling was for more of a broad audience and ours was for a little audience—cult, a niche, whatever you want to call it.

Kevin Murphy: I think it is in the nature of middle-ground studio executives to feel obligated to dick with things, even if they don’t need dicking with. There was a lot of dicking with what we did. You’re getting script notes from these people who had never written a joke in their lives. That was always hard to take.

Michael J. Nelson: It was like, “We’ve had the live show. We’ve seen audiences react to our jokes. We know how they play, and that’s the movie.” They were like, “Yeah, but we’ve got to goose it up.” [We were] like, “Well, not really. We’re giving people a big juicy steak with butter on top. It’s delicious and you’re worried about the spinach salad on the side. That’s not the big concern.”

It was working with people who had not done any comedy, and I liked all of the people that we worked with. There were no character issues. But the comedian guild is strong, I’ll just say. We were all comics, like true comics. People who aren’t comics are just on the outside. It’s just like a guild. You’ve been up onstage, you’ve driven to a North Dakota sports bar on a Friday night and almost got killed. You’re part of a team, you’re a Spartan.

Mary Jo Pehl: We were not used to working with any sort of studio oversight and getting script notes every time we turned in a version of the script. We were not used to justifying or having to explain jokes. I think that was really frustrating for us because we have the sensibility that if you got it, great. If you didn’t get it, you’ll get the next joke. I don’t think we were used to it being so under a microscope. And when you start disassembling a script like that, any MST3K script, it’s not going to hold up to the same parameters of a narrative script. I felt like a lot of those principles were being applied to this unusual beast.

Bridget Nelson: We just riffed the movie like we normally did, and then just kind of kept going through it and through it. And then, of course, the executives don’t get funny jokes. They’d be like, “Oh, you can’t have this and you can’t have that.” And we’re just like, “This is so stupid.”

Michael J. Nelson: One of the things that it does, I have to admit, is make you grow as a writer. To just go, “Okay, you don’t like that joke? I can write you 10 more then. That’s fine.” But it takes awhile to get to that stage because you’re like, “This is a good joke and the fact that you don’t get it…” That was a tough note to get: “We don’t get this.” And you’d go, “The fact that you don’t get this means you’re an idiot.” But you can’t say that.

Jim Mallon: There is a famous singer named Bootsy Collins, who bore a resemblance to the rubber-suited monster in This Island Earth. So [when] we first saw the rubber-suited monster, the comment from our crew was “It’s Bootsy Collins.” Well, the executive in charge didn’t get that joke. Now we’re supposed to get rid of something that was an obvious riff from our perspective.

Trace Beaulieu: I defy you to look at that thing and not say it looks like Bootsy. And [the studio] said, “No. How about Leona Helmsley?”

Jim Mallon: I know at one point we had a reference to a Beatles song. Well, the music clearance [department] went to The Beatles’ representatives and they wanted to charge, like, $100,000 just for that five-second reference. That ended that. In the TV series, we would’ve just done it because nobody was watching that closely. It kind of took our breath away.

Trace Beaulieu: It’s hard to stick to what your core is when you’re faced with, “Oh, yes. You are giving us the money to do this. Of course we’ll make those changes.” But we’d grumble about it later because we’re all comics. I think we wrote it into the show, our disdain and pain.

Jim Mallon: It was surreal to us because it was like having a rock band that was established, say someone like R.E.M., and then you put them in a new environment. Then the executives in the new environment start telling R.E.M. how to write its music. You’d be scratching your head and going, “Why do they need to tell us how to do what we do?”

Michael J. Nelson: I always thought we were similar to a band. I feel a close affinity, because I love them all and I’ve read their book, to The Replacements. Just being outsiders who suddenly have a little bit of a spotlight shown on them—not a very big spotlight, not very powerful—and there’s just that Midwest energy of “Look, we know we don’t belong here. Let’s have some fun with this.” So I was very protective of the fact that “No, we’re a band. We can do funny stuff regardless.” And then the machine started and I was very concerned about that. I had a lot of anxiety about that. I just loved all these people and I was so proud of what we did with so little. It was so much fun. And then all the sudden it became bigger. That’s every band’s story, right? They get some success and then they don’t know what they are anymore. I was a little worried about that.

Once the script was finalized, the MST3K crew next embarked on actually shooting the film. Though they kept the production in the Twin Cities and maintained some of their local staff, the production moved out of the Best Brains studios. A massive set (by their standards) was built in the new Energy Park Studios and the film’s riffing was recorded at Prince’s Paisley Park Studios. Those on the set felt the pressure and exhilaration of the process. At the same time, Mary Jo Pehl simultaneously worked on another beloved entry in the show’s history—The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide.

Jim Mallon: The trick to Mystery Science is that the show was always a function of its budget. It was a pretty low-rent show out of the gate. We had no money. But the audience accepted the show as it was and didn’t complain that it didn’t have high-end special effects. They kind of liked the low-rent, do-it-yourself quality of it. So it became very difficult when we got to the movie to figure out how to translate the show to the big screen and retain fidelity with the series.

Kevin Murphy: Considering that we built the whole [TV set] with Makita drills and hot glue, 2 million bucks felt like all the money in one respect. I think we built bigger sets since we knew it was going to be on a wide screen. To just make it look a little bit bigger without making it look Hollywood. Because you couldn’t do a Hollywood movie on $2 million. Not a science fiction movie.

Michael J. Nelson: [The budget] was like 90% of our creative talks. There were so many different, shifting things. Universal Studios, they are harsh about budgets. I mean, that’s their job. But that was really tough, the budget. In the early conceptual days, it was like, “Look, if we make something that looks smooth and cool, is that a different aesthetic? How do we control that? We don’t have experience with that.”

Jim Mallon: Our budget was so tight. It was even tighter because working with a big studio like Universal, they have mandatory things like an Dolby license. Universal had an agreement with Dolby to pay them $5,000 a picture, no matter if it was a $190 million film or, in our case, a $2 million film. And so that took a big chunk out of our budget. It was tricky. They were trying to keep it under the radar, so we really didn’t want to push things.

Bridget Nelson: To get to an orbit where you start getting attention on a national level, life becomes a little weird. In some ways, we enjoyed life in a lower orbit—just enough to sustain us for 10 years. So there’s a trade-off. The tough thing is, how do you preserve the integrity of the show when you have different executives with different agendas drifting in and out of the project?

Trace Beaulieu: In some ways there was less control because there were more departments involved in the actual building of stuff. I don’t know why we couldn’t have done it on the same scale as the TV show, because that had more of an intimacy. The set, to me, was too big. I never liked that idea. We had watched Das Boot to see how a claustrophobic environment could be portrayed. And then we went, “Alright, let’s just make it bigger.”

Michael J. Nelson: I was very concerned about getting on this big set and going, “How does the comedy happen?” It was just very different to me. So I felt a lot of unease walking into a movie set and having the key grip yell at me: “Hey, lookout buddy! Get the hell out of my way! Who the hell are you?” “I’m just a guy trying to make a funny little sketch.” That was weird. It was a weird adjustment.

Kevin Murphy: We rented a studio in town, Energy Park in St. Paul, and we built sets there. We had a great crew. It was one of the most amazing things. We were able to call on old friends of ours. Tom Naunas, who does sound for public TV in Madison. Jeff Stonehouse, who was our cinematographer for the last few seasons of Mystery Science Theater 3000. Bill Johnson was an editor from Hollywood and a friend of our agent—the sweetest guy in the world. And we got to meet all kinds of fun new people who entered into our world because now we had a movie. We had an honest-to-goodness professional crew, from Minneapolis mostly, on board. The most fun thing of the whole experience was being on set. Most of the time between takes I spent playing Doom with Mike. Mike was brutal. Mike was extraordinarily talented at Doom. He was like the Mozart of Doom. And he always let you know that, too.

Mary Jo Pehl: I love being in that environment. It’s so fascinating to see all these amazing people doing their jobs, making a set come together. We just have amazing talent here in the Twin Cities, and it was really great to be exposed to that and learn the workings of it. I mean, it was really beautiful to see these gorgeous sets come together. Just really exciting.

Kevin Murphy: One of my favorite parts of the whole movie is Trace Beaulieu’s introduction to the movie, the cold open. Trace, as Dr. Forrester, explains the whole premise of the movie right there in the first three minutes, and it was a single shot. I think he nailed it on the first take. That was one of the first things we shot. And so it was very exciting. Trace did such a great job.

Michael J. Nelson: There were two studios: one was the Paisley Park Studios, that was where we did the actual lines in the movie, and then the other one was [Energy Park] in St. Paul.

Kevin Murphy: We got to go over there, to the Purple Palace. We never did see His Royal Badness stalking around the place, but we knew he was there.

Michael J. Nelson: The manager of the Energy Park Studios was the former manager of Prince’s [Paisley Park] studios, so he had great stories. I remember just sitting and talking with him forever and going, “This is such great Prince stuff.”

When we went to record the dialogue for [the film’s riffing], we went to a studio and it was like one take and done. And then we said, “Well, should we do another? I think we have the studio for three days. We probably should do at least another take.” But it was not necessary. It was like a normal taping.

Mary Jo Pehl: While the main team were at the studio working on the movie, Paul [Chaplin] and I were working on The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide. When the movie was being shot, everyone else was away at the studio. But Paul and I were at the Best Brains studio, working on the book. It was revisiting a lot of the recorded MST3K episodes to refresh our memories, distilling them into a summary, and then reviewing our own work. Then [it was] assigning different people to contribute stuff. Like I know Kevin has an essay in there, Mike, etc. So it’s getting that all organized. It was pretty workaday. I mean, no complaints. Who wouldn’t love a job like that?

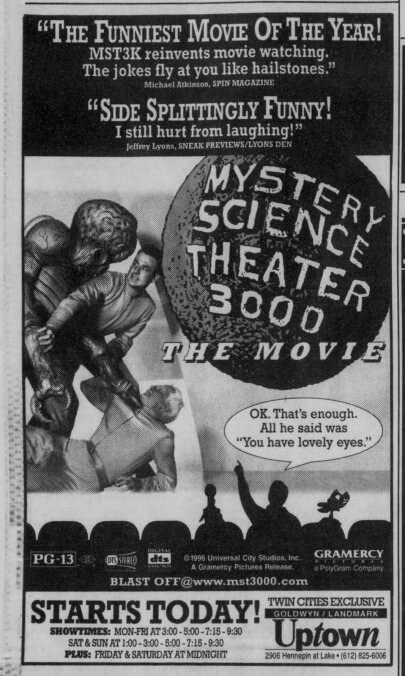

After wrapping principal photography, the MST3K crew grappled with new demands from Universal during the post-production process, including reshoots and dramatic cuts to the film’s runtime. Even worse, the studio showed little interest in the movie’s release. Though the film’s premiere at Minneapolis’ Uptown Theatre (the venue where riffs for the movie were first tested) was a rare bright spot during this period. At the same time, the TV show’s fate also hung in the balance as Comedy Central declined its renewal. This harrowing period may have shaded some perspectives on the film itself. But for fans, like MST3K’s current host Jonah Ray, the movie has left an indelible impact.

Jim Mallon: One of the things that I grew to respect was how good films come out of the Hollywood system. There are plenty of good films, but it must take extraordinary people to help keep the process from destroying the joy in those stories. We experienced the Hollywood process as a pretty joyless affair. And that was the difference, because our show was joy-driven. We just did it for the hell of it. We [started] on the last-rated TV station in Minneapolis. There was no money in the beginning. It was really about it being a fun thing to do and fun people to be with. So it was really a head-turner to get into a system which wasn’t about that.

What we learned through the making of the movie is that [for] the executives in charge of the production, the quality of the movie is down a few notches on their agendas. They’re trying to move their careers forward. They’re trying to please their bosses. They’re trying to please the other people in their company to get their projects favored and moved forward. They want to go to the film festivals. All these things take precedence.

Mary Jo Pehl: I was completely amazed at how the studio system works. All the clichés about L.A. showbiz types, at least at that time, were manifest in the people who we reported to for the movie. It was frustrating for me. I can only imagine how frustrating it was to the principals.

Michael J. Nelson: [The studio was] going line by line: “This joke got 60% less laughs. Let’s redo it.” It was just so far down the road at that point. It was like, “Some audiences will get it. We have 700 jokes, it’ll be fine.” We did reshoots for the [host segments], I remember, which I thought was just bizarre. I don’t remember what it was, but we had to get the whole soundstage up and running for the [host segment reshoots].

Jim Mallon: They cut some of the host segments, which sort of breaks my heart. I ran Gypsy in one where she saves Mike. A meteor hits the ship and it starts running out of air, so they go into a safe room. And then they run out of more air. It doesn’t affect the robots, obviously, but Mike is starting to get woozy. So Gypsy swallows Mike’s head with her mouth and gives him oxygen. That was cut.

Kevin Murphy: Somewhere on the internet you’ll find the storm cellar sequence, which I think actually was one of the most fun sequences we did. There’s a meteor shower and they’re all sent to the basement, where Servo keeps a huge stock of hash—canned hash, not the drug hash. A meteor hits and Mike gets stuck underneath a beam and [the bots] work together to save him. It was the silliest thing we did and ended up on the cutting room floor. Frustrating.

Jim Mallon: A lot of the cuts came from this executive named Carr D’Angelo. If you look at the chainsaw that Crow holds in the movie, the name of that brand of chainsaw is Carr. That was done intentionally because he was the one that was cutting things. Ironically, he tried to get that prop when we sold all the props from the series. But there’s a guy on the internet who specializes in getting chainsaws from movies out there and he outbid Carr D’Angelo. So he never got it.

Bridget Nelson: They made it be so short, which really stunk. The people pay their money and they don’t even get a 90-minute movie. Come on.

Kevin Murphy: Casey Silver, who was the boss of production at Universal at the time [said], “It’s too long. Cut it down.” “Casey, it’s like 85 minutes.” “No, it’s too long. Cut it down.” The irony is we ended up being shorter than most of our episodes.

Michael J. Nelson: We just didn’t have an angel on the inside. It was always being shuffled around to people and they would look at it and say, “I don’t get it. Cut it down.” That kind of stuff. At that point, I really remember just feeling, “If it comes out, it comes out. If it doesn’t, I don’t care anymore.”

Jim Mallon: The whole audience-testing thing was a surreal chapter of it. They put us in a theater in L.A. and did [survey] cards. That was so painful that we wrote a sketch for one of the TV show’s episodes where we product-tested Crow’s film “Earth Vs. Soup.” That was just processing the pain of Universal testing Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie.

Michael J. Nelson: I will tell a story that I think is very funny. I’m going to get in trouble for this. Who cares. What the heck, I’m old. I’m fine. We did a screening in Hollywood, and it was weird. It was like in the middle of the day, and it was all teenagers. I don’t know how they shoveled this group of people into this theater, but it was very rowdy and it was not landing. I swear, it was just because people didn’t know what it was. It was like, “Look, I’m just getting some air conditioning,” or something. A very strange thing. And Jim Mallon recorded it with his own recorder from the back of the house. Then the studio said, “You recorded it? We want that tape.”

He couldn’t deny that he had recorded it. Oh, man, should I be saying this? I don’t know. We gave it to our sound engineer and told him, “Just destroy the sound and pretend that’s the way it was.” So, we gave them a destroyed tape. I remember this subterfuge being like, “Should we do this? We can’t give them the thing because they’re going to then react to every joke.” So, we were at the end of our rope and we did that. And they said, “We got the tape and it’s unusable.” “Oh, really? Okay.” At that point, we just didn’t want to give them any more ammo.

Jim Mallon: Another whole chapter of this is the marketing of the movie. It was done through [Universal’s] boutique studio called Gramercy. And at the time, they had two films that they were releasing: One was ours, and the other was a Pam Anderson film called Barb Wire.

Michael J. Nelson: We go to our PR person in Manhattan, and she’s like, “There’s going to be a big push on this. Big push.” But she was also promoting Barb Wire. So her promotion budget was all focused on Barb Wire, because they knew that it was going to only do one week. She’s like, “We have to get it out there in the first week because it’s so terrible.” And we said, “Uh oh.” We looked at each other and went, “That means they just spent all their money on Barb Wire.” We were actually in her office and she had 35mm cans of Barb Wire just sitting there, tons of them. She said, “You want one? Take it.” Unfortunately, I could not grab an original 35mm print of Barb Wire because I just couldn’t fit it in my suitcase. But then on the way out of the office, we went, “Well, we’re doomed. They spent all of their money on Barb Wire.” And she pretty much said that “So for your movie, we have nothing but we’ll do what we can.”

Trace Beaulieu: Well, Pam was hot. Pam had a following. But I’ve still never seen the movie. And that’s not out of spite—I just don’t care. We had high hopes. We wanted [our movie] to be a success and have a life. But it was only on [26 screens].

Jim Mallon: You can imagine, from a PR perspective, where the money went. Even though we did quite well in the theaters, they just didn’t put us in many. We really only knew what we heard or what people told us. Could be that some muckety-muck at Universal took a look at the film and didn’t like it, so they just put the money into Barb Wire.

Kevin Murphy: Essentially what we were learning was they were going to let this film wither and die. That’s it. After it first came out and a couple of weeks went by, we stopped getting calls from Universal about that time.

Mary Jo Pehl: There was a premiere at the Uptown Theatre in Minneapolis, which has been around for ages. I went there for years because it’s one of those great, old arthouse movie theaters. The programming was amazing. I saw so much stuff there.

Trace Beaulieu: That was especially fun for me because that was the theater I went to for all the midnight movies and cult movies throughout the 1970s and 1980s. That theater was important to me, and I think all of us lived in that neighborhood at some point.

Michael J. Nelson: I think that was a very fun closing for us, to see it with a very enthusiastic crowd. It’s not a huge theater, but it’s pretty big. It had all the trappings but it was also very Midwestern. So that was fun, because I’m not sure a Hollywood [premiere] would have made any sense or made anyone feel very happy.

Jonah Ray (Host/Writer/Producer, Mystery Science Theater 3000, 2017-present): I was a huge fan of the show and I knew there was a movie, but when there was a movie that was kind of small, it would rarely ever play in my town. I grew up in Oahu, Hawaii. And so there was kind of one theater that would sometimes do arthouse or smaller stuff, but I kind of knew for a fact that I wasn’t going to be able to see it.

But luckily around that same time, I took a trip to see my uncle and aunt in Carson City, Nevada. The last night I was there, my uncle was like, “Hey, I’ll take you into Reno tonight. We could go see a movie or something like that.” I said, “Sure.” So I look in the paper and I lose it. I say, “We’ve got to go see Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie!” I can’t believe it, I’m going to get to see it. What a lucky shot that this is one of the 12 theaters across the country that it’s playing in the week it was out. I remember being just so excited to see it on the big screen and hearing it so loud—being able to see it and have it be such a special moment with my uncle. I loved all the shows, but the movie is such a solid memory of mine.

Mary Jo Pehl: If memory serves, it was this kind of overlapping period where we were still working on the next season deal with Comedy Central. I think we were worried about the future of the show because the season was so truncated and we didn’t know where we stood.

Trace Beaulieu: I think relationships kind of soured between Best Brains and the network. Otherwise, I think they would have heavily promoted [the movie]. Because we were on that network, at our peak, something like 24 hours a week.

Michael J. Nelson: It was unsure whether we would get the Sci-Fi Channel era at all. So it was kind of like, “Well, maybe this is the end of it all. I don’t know.” That was kind of my sense, that it could be.

Kevin Murphy: It was, like, the in-between time. Between Comedy Central and Sci-Fi Channel. [The movie] kept everybody employed for a while, which was really nice, until we got back on TV again.

Jim Mallon: [The movie] holds up pretty well. It’s decent. I don’t think [This Island Earth] was the best Mystery Science movie. It was not bad, but it wasn’t the best. Given the gauntlet we had to go through to get the thing made, I’m fairly impressed with the finished product.

Bridget Nelson: I have not seen it in years. So I probably should. It’s like when you write a term paper and you hand it in—you never read it again. It’s a little bit like that.

Mary Jo Pehl: I have not seen it since then. And I’m wondering why I haven’t seen it. I’m wondering if it left kind of a bad taste in my mouth because of the difficulty of working with the studio. And I say that as a person who takes it personally and didn’t want to have to explain jokes. I’m just curious about why I haven’t seen it since then. We worked so hard, we were so devoted, we were all really committed to our little TV show, and then the studio was such a pain in the ass. And then they just abandoned us. So maybe there are deeper issues I need to see my therapist about.

Trace Beaulieu: I got to see the movie projected in the early 2000s. I saw it projected in 35mm at a film festival in Utah. It was cool to see the film again with an audience, and it worked. It was meant to be seen in a theater with people. But people have come up to us at our [live] shows and say they love the movie. We’ve signed laser discs copies of it, which is cool, or DVDs. My favorite are the VHS with the neon Suncoast label on it, and it’s marked down to $4.99.

Jonah Ray: They had the video cassette collections of the show, but I couldn’t really afford to get all of them. I was always so scared to start because then I would want to be a completist, and I didn’t have the money to be a completist. So when I was at the mall and I went to a Suncoast Motion Picture Company, they had the Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie on VHS. I was so excited because I was like, “Well, I know that one is good, so I can just get that one because it’s the movie and it’s kind of singular.” Unlike the show, it couldn’t be rerun. It was never rerun on TV or shown on TV. But I had the video, so I could watch it over and over again.

I was getting into the habit of just listening to movies that I knew well to go to bed. So I’m listening to this episode, essentially, and every time I go to bed it’s seeping into my unconscious. It becomes part of my vernacular. I quote it to my friends. I make my friends watch it. The rhythm of it, I loved it. I thought it was such a great episode. I thought the riffs were fantastic. I thought it was nicely paced. I like the length of it—I know it’s a little shorter. The sketches are fun and feel bigger. It was what I wanted from a Mystery Science Theater 3000 movie.

Michael J. Nelson: It grew on me over the years. I had a lot of anxiety about it because, as a head writer, I was so concerned about the comedy. I was so concerned about the sacrifices that we had to make and just the undercutting of our own comedy, then the cutting of the actual length of the film, and the re-shooting and everything. It just was so disorienting. And so when the final product came out, I don’t know that I could view it in a way. All I looked at was the hard work and the pain of it. I was like, “It’s okay.”

Jonah Ray: With something that was hard to make, the experience of making it supersedes anything you made. So when someone goes, “Oh, that thing you did is great,” you just immediately go, “Well, it rained that day and I stubbed my toe and then someone rear-ended me on the way home.” It’s almost this painful memory for them, the making of it. It’s not as joyous as it being a huge fan and getting to see it in the theater.

Joel Hodgson: But here’s the thing that I think is really important about the movie: The riffing is very strong. I don’t think the sketches are that great, but the riffing is really strong. It’s especially good. And I think that it just shows that instead of us just taking a week to write it, they took two weeks. It just shows you what’s possible. When I brought the show back for Netflix, I looked at [the movie] and said, “That’s right.” That was an indicator to me. It was widescreen, with a great print, and it’s nice-looking. When you look at the show now, that’s where we are at. We use widescreen movies whenever we can and they’re all really nice prints now. We kind of upped our game.

Kevin Murphy: I’ve heard [people say it’s their favorite] a few times. I’ve worked with Jonah Ray a couple of times subsequently, and he says it’s one of his favorite MST3K things. And I’m like, “Really?” I think it’s because, again, it was really fun to make and I think that shows up on the screen. But there was also just a lot of pain working with a big studio.

Jonah Ray: There’s a line from This Island Earth, I love the little couplet of it: “You know what the kids would say?” “You’re not my real father!” “This is crazy mixed-up plumbing.” I started saying that. And then my friend Donald—we got into the show together—I said to him when we were still in high school, “If I ever do stand-up comedy, my first album is going to be called This Is Crazy Mixed-up Plumbing.” This is a conversation I had when I was, like, 17 and I was like, “And my second one is going to be called Hello, Mr. Magic Plane Person, Hello,” which was another line from the movie. I would say it every time I was coming over to my friend’s house or getting into his car. And then I did. I put out those two records with those titles. That’s just how much the show means to me. It means the world to me.