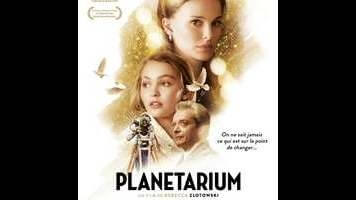

Natalie Portman helps commune with the dead (or does she?) in the muddled Planetarium

Numerous potentially interesting ideas orbit one another in Planetarium, but none boasts sufficient gravity to merit a landing, it seems. Set in 1930s France, the film begins intriguingly enough, introducing Laura (Natalie Portman) and her much younger sister, Kate (Lily-Rose Depp), as they perform a public séance for a large paying audience. Kate makes contact with the spirits, while Laura orchestrates the human drama (accompanied by a bongo drummer, for some reason); initially, it’s unclear whether they’re con artists or we’re meant to accept Kate’s gift at face value. Certainly, wealthy film producer André Korben (Emmanuel Salinger, the star of Arnaud Desplechin’s early films) believes them, as he first arranges a private séance, then invites the two women to live with him, then arranges to have them star in one of his movies, more or less as themselves, hoping to actually capture a ghostly image on camera. Which all sounds very promising, except that none of this ever develops into anything concrete, with the exception of some ungainly historical subtext. Planetarium proves to be spectral in more ways than one.

A big part of the problem is how determinedly vague everything is. Portman (who performs much of the film in what sounds like pretty fluent French) is 36 years old; Depp (daughter of Johnny, with whom she was previously seen in Kevin Smith’s Yoga Hosers) is 18. It’s not strictly necessary for the film to explain the age difference, but Laura and Kate often seem more like mother and daughter than sisters, adding an unintended note of ambiguity that distracts from the intentional variety. Depp’s performance as the medium can only be described as noncommittal—even after nearly two hours, it’s hard to say whether Kate feels blessed or cursed by the path her life has taken, or whether she feels much of anything at all. Planetarium seems invested primarily in drawing blunt parallels between cinema, spiritualism, and certain characters’ studied indifference to the threat of war in Europe, especially for Jews and foreigners. But this theme, while potent, remains strangely detached from the events that are designed to illustrate it.

Both the film’s writer-director, Rebecca Zlotowski, and its co-screenwriter, Robin Campillo, have wrestled with this issue before. Fans of the French TV series The Returned would likely be bewildered by its direct inspiration, Campillo’s 2004 film They Came Back, which has exactly the same premise (the dead in a small town return to life, not exactly as zombies) but remains frustratingly blasé about it. (On the other hand, Campillo’s Eastern Boys could scarcely be more direct, and his latest film as director, 120 Beats Per Minute, won the Grand Prix at Cannes last May.) And there’s a reason why Zlotowski’s two previous features, the woolly Dear Prudence (2010) and Grand Central (2013), never got U.S. releases. Her formal approach here, which combines a wide-screen aspect ratio with suffocating close-ups, seems equally confused, as if she’s just trying things at random without thinking them through. The result is a maddening jumble of impulses forever in search of a satisfying whole.