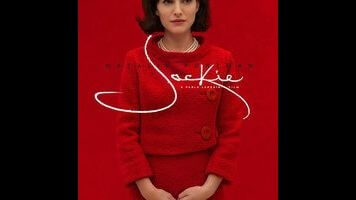

Natalie Portman reveals the artifice and the agony of Jackie in an arresting biopic

It’s tempting, at a glance and an early listen, to dismiss Natalie Portman’s performance in Jackie as a distracting impression—the usual collection of precisely replicated tics that movie stars often adopt to portray real people. Portman has been cast as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the former first lady of the United States, and when the actress first steps on screen—her hair cropped into that signature bouffant, her breathy voice a reasonable approximation of the Onassis purr—every line and mannerism comes across a little studied, a little practiced. Then again, wasn’t that also true of the real Jackie Kennedy? Wasn’t her life in the spotlight its own kind of performance, down to the imitable mid-Atlantic accent she willfully acquired in prep school, and which Portman—embracing the affectation—skillfully mimics here? Jackie, too, was playing a Kennedy. She was just doing it for a much larger audience.

Anyway, there’s nothing very mannered about subsequent scenes of Portman, clad in a blood-speckled pink suit, quaking with rage and grief. Watching one famous person play another may cause some cognitive dissonance, but the real contradiction of Jackie is the vast chasm separating its subject’s fairy-tale dream-life from the national-stage nightmare it curdled into after her husband, the president, was shot dead in the car seat next to her. Like many of the best biopics, Jackie doesn’t attempt to tell a life story, instead focusing on a single significant chapter—namely, the horrifying climax of Jackie’s time in the White House. But director Pablo Larraín (No) goes further than truncating the timeline; he also takes an arrestingly subjective vantage on historical events. “This will be your own version of what happened,” a reporter (Billy Crudup) reassures Jackie when she agrees to break her silence—and indeed, the movie often plays like some surreal dramatization of her first-person account.

The opening hour unfolds in a bubble of exhilarating disorientation, laying out the harrowing aftermath of Dallas in elliptical vignette: Jackie cradling JFK’s hemorrhaging head, trying to keep it intact, as the motorcade races down the highway to safety; Jackie, adamant about remaining in her drenched clothing, watching as Lyndon Johnson (John Carroll Lynch) is sworn in on Air Force One, just two hours after the shooting; Jackie, still plainly in shock, breaking the news to her children. Larraín provides no reliable sense of passing time, letting the sleepless hours bleed into sleepless days. His cinematographer, Stéphane Fontaine, who shot the intentionally banal-looking Elle, gets queasily close to Portman, his camera as invasive as the ones that rendered Jackie’s private agony public. Some of the pair’s juxtapositions have a cruel before-and-after irony, as when an early mirror shot of Mrs. Kennedy applying her makeup is itself mirrored by another shot of her wiping blood and tears off her face, later the same fateful day.

The most conventional aspect of the film is its framing device, in which a bitter, mourning Jackie sits down for a highly mediated interview with Crudup’s journalist at one of the family properties in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. We didn’t necessarily need flashback prompts to realize that these vivid visions of the week from hell, coupled with snapshots of the Kennedys’ life of luxury, represent a string of memories. At the same time, Jackie uses its conversational interludes—in which the widow provides candid answers, only to retroactively strike her comments from the record—to reinforce a conception of the first lady as her own savvy publicist. “I don’t smoke,” she tells the reporter, between drags on her cigarette, and the film contrasts the behind-closed-doors Jackie with the all-smiles version who appears in a reenacted 1962 documentary, leading the first televised tour of the White House. (Her renovations to the building, showcased during the TV program, demonstrate how Jackie helped shape not just her own public image, but also that of the whole Kennedy dynasty.)

For Portman, this isn’t so much the role of a lifetime as maybe the roles, plural: The notion of multiple Jackies affords her a range of personas, from the poised debutante to the knowing media manipulator (“I love crowds,” she tells John at the airport, sarcasm on her breath) to the shattering, bereaved spouse. For Larraín, the film is the latest in an ongoing line of stylistic pivots. The Chilean director has three films in American theaters this year—including last spring’s disgraced-priest drama The Club and another biopic opening in just two weeks, Neruda—and none of them resemble each other in the least. He shot Jackie, his first film in English, on grainy Super 16, which undercuts the glamour of 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. with a little gritty texture, while also allowing Larraín to match his own footage to archival snippets. The filmmaker’s shrewdest move, though, was securing the discordant contributions of English musician (and Under The Skin composer) Mica Levi, whose lonely horns and whining strings steer the film away from the emotional pitfalls of prestige cinema, providing a thick unease in the process. It might be the soundtrack of the year.

Jackie doesn’t completely sidestep its genre’s sentimental conventions. The film eventually abandons the experiential horror of the early scenes in favor of agonizing over funeral plans, references to the King Arthur stories (the Broadway hit “Camelot” gets not one, but two airings), and one too many speeches about legacy, as Jackie works out her fears and anxieties in conversation with a priest (John Hurt, exceptional), an anguished Bobby Kennedy (Peter Sarsgaard), and a loyal confidante (Greta Gerwig). But if the screenplay by Noah Oppenheim (The Maze Runner, Allegiant) gets a little too on-the-nose in spots, it also takes the Kennedys’ existential crisis seriously; like anyone else, they just wanted to know that they mattered, that they made some mark on the world. And if Larraín ultimately can’t resist treating his subject like an icon (albeit one complicit in her own lionization), at least he also acknowledges the intense pressure that status must have put on her—not to mention the furious, neurotic, devastated person beneath the facade. Jackie shows us the facade and the beneath, which is just one way this boldly off-kilter movie puts its biopic brethren to shame.