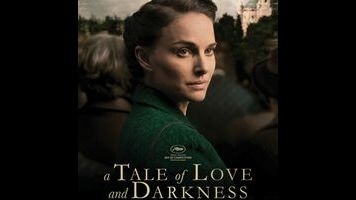

Whether it’s called a memoir or a “nonfiction novel,” autobiographical writing generally belongs to one of two categories. In the first, a person who’s lived a remarkable life, or has briefly experienced some extraordinary events, narrates a series of personal adventures: “This is what happened to me.” More common, though, is the second variety, in which nothing especially earth-shattering takes place, but tremors arise from the writer’s perception and processing of events: “This is how what happened to me felt.” While both are totally valid approaches, narrative-driven memoirs tend to work better as movies—think 127 Hours, The Pianist, Catch Me If You Can. Translating the internal, mood-oriented type to the screen is tricky business, and that’s the challenge Natalie Portman took on when she chose to make her directorial debut with an adaptation of Amos Oz’s 2002 bestseller A Tale Of Love And Darkness. Portman’s emotional connection to the material couldn’t be more obvious, yet the film itself is still largely inert.

Born in 1939, Oz (played in the film primarily by young newcomer Amir Tessler) grew up in Jerusalem with his father, Arieh (Gilad Kahana), and his doting mother, Fania (Portman). The movie sticks mostly to his memories from 1945 to 1952, as he observes Israel come into being. Initially overjoyed to finally have a state of their own, following years of persecution, Amos’ parents are decidedly unprepared for the violence that follows; at one point, most of the tenants of their building wind up living in their basement apartment, in an effort to avoid being shot and/or bombed. Ultimately, though, what permeates A Tale Of Love And Darkness isn’t the First Arab-Israeli War itself, but its effect upon Fania, who’s afflicted by what would almost certainly be diagnosed today as clinical depression. (The word “depression” is never once spoken, which seems accurate for the era.) Even in the film’s early scenes, Fania tells Amos stories that are disturbingly grim; eventually, that grimness threatens to swallow her whole, and he can only watch.

Portman wrote the screenplay in addition to directing, and she includes occasional voice-over narration (presumably taken from Oz’s book) that floats intriguing ideas. Most notably, Oz suggests that Israel was more beneficial to the Jewish people as a hopeful dream than it could ever have possibly become as an actual country—that its formation was fundamentally destructive. That’s a provocative thesis, but it’s abandoned virtually the moment that it’s raised; there’s no credible way for Portman to explore it via the actors, the dialogue, or the imagery. At other times, she’s clearly restricted by a low budget. We see a few individuals get shot, and one scene features what looks like a whole lot of computer-generated black smoke, but a full-fledged war was beyond the film’s means; some quick archival footage has to suffice.

Given the eventual emphasis on Fania’s mental state, that’s not ruinous. Still, the basic problem here is simple: This is a movie, and there’s nothing much to look at apart from a woman staring disconsolately into space and a little boy staring at her sadly from a few feet away. Depression is a notoriously difficult subject to dramatize (for a valiantly expressionistic attempt, see Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia), and Love And Darkness traffics almost exclusively in visual clichés; its money shot has Fania sitting outside in the pouring rain, because filmmakers decided long ago that you know someone is upset when they don’t care that they’re getting wet. (The suburban version of this trope involves sitting in the path of a sprinkler or being fully dressed in the shower.) Portman’s commitment to making the film almost entirely in Hebrew, with no stars apart from herself, is admirable, and she demonstrates some talent behind the camera, particularly in realizing the stories Fania tells Amos. But it takes a genius to craft a movie from material that’s deeply rooted not just in words, but in feelings that are so complex as to be nearly indescribable. Even Stanley Kubrick didn’t start with Lolita.

Purchasing via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)