Beats, Rhymes & Life: Michael Rapaport’s riveting hip-hop documentary Beats, Rhymes & Life gets uncomfortably close to A Tribe Called Quest, one of the most important and influential groups of the past 25 years. It’s at once a loving, magnetic and gloriously alive tribute to a golden age when a group of brilliant black men and women barely out of their teens joined forces to reinvent hip-hop in their own funky, Afrocentric image under the banner of Native Tongues, but it’s also the most penetrating psychological study of a creative partnership in perpetual peril since Metallica: Some Kind Of Monster. Why is it that the sunniest groups often have the darkest, most fucked up intra-group dynamics? Listening to A Tribe Called Quest or the Ramones or Beach Boys, you’d never imagine that the principals in each group were locked in decades-long psychodramas.

Rapaport smartly focuses on the yin-and-yang duo of Q-Tip and Phife Dawg. The group’s lead rappers are a study in contrasts. Phife Dawg is heartbreakingly vulnerable, a mild-mannered, sweet-natured little man with an excitable, girly voice and a debilitating case of diabetes.

Everything about Phife is sweet and messily human, even the addiction to sugar that put his health and the group’s future in peril at the height of its powers. Q-Tip, who has understandably ambivalent feelings about the film, emerges as Phife’s polar opposite, a quietly authoritarian bohemian control freak and musical genius. He’s cold and calculating where Phife is sincere and earnest, ridiculously dapper and well-preserved (when did Q-Tip start looking and dressing like a GQ model?), where Phife looks like what he is: a very sick and vulnerable middle-aged man. Phife is also winningly self-deprecating where Q-Tip radiates frosty arrogance; it’s hard not to love a long-suffering sidekick who compares his plight in his more illustrious and successful former partner’s long shadow to those of Florence Ballard and Tito Jackson.

Beats, Rhymes & Life begins as an ecstatic celebration of a group that changed pop music forever while its members were still young enough not to be intimately familiar with their limitations. Q-Tip’s perfectionism and surgical focus helped elevate hip-hop to an art form, but as Phife got sicker and the vibe within the group got frostier, Q-Tip’s controlling ways began to take on a bullying, hectoring quality. In one of the most heartbreaking moments in the film, Phife, weak from intensive treatments for diabetes, leans on his best friend Jairobi for support, only to be bitched out onstage in front of thousands by Q-Tip for ostensibly slacking.

Beats doesn’t begin to pretend that the group’s periodic reunions are about anything other than making big-ass paydays; in a characteristically candid moment, Rapaport asks members of De La Soul if they want Tribe to get back together, and without much hesitation, they say not if it’s only for mercenary reasons, which the occasional reunions very clearly are.

Poignant and powerful, complex and melancholy, Rhymes ends with rehearsals for yet another money-grubbing comeback tour. For one shining moment these complicated men are moving and grooving in unison once again, united by the music that is their lasting legacy, even if by that point we’re all too intimately acquainted with the abundant darkness just out of the frame. (A-)

Cedar Rapids: Ed Helms once again channels his inner Steve Carell as a guileless Wisconsin insurance agent whose gee-whiz exterior masks an even sunnier, more innocent and optimistic interior in Miguel Arteta’s Alexander Payne-produced comedy Cedar Rapids. Helms’ overgrown boy scout bears a close enough resemblance to Carell’s middle-aged abstainer in The 40 Year Old Virgin to suffer by comparison. The film follows suit.

Cedar Rapids boasts a game lead and a terrific supporting cast led by John C. Reilly, The Wire’s Isiah Whitlock Jr., Anne Heche, Stephen Root, Rob Corddry, Thomas Lennon, Alia Shawkat, and Kurtwood Smith (Christ, that epic cast list makes the film sound like the new Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, not a small-scale comedy), but all too often settles for a sort of Midwest minstrelsy as it documents one extraordinarily eventful conference where Helms’ innocence is corrupted and his character tested at every turn. Cedar Rapids improves as it progresses and becomes more goofily kinetic. Reilly is predictably fun as a rampaging id running roughshod over the squares in his midst, and Heche is poignant as a mother and wife with a history full of regret and one-night stands, but Cedar Rapids banks far too heavily on the audience’s superior distance from its characters. It is nice, however, to finally see a film at Sundance about an unlikely gang of misfits who come together to form an unconventional but loving makeshift family. (C+)

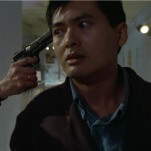

Kaboom: At the time of its release, it was unclear whether Mysterious Skin represented a bold evolutionary leap forward for writer-director Gregg Araki or an aberration. On the basis of first the flimsy but ingratiating Smiley Face and now the lighter-than-air trifle Kaboom, it seems safe to assume Araki won’t be scaling the creative heights or embracing the restraint and maturity of Mysterious Skin again any time soon. With Kaboom, Araki returns to his comfort zone of campy comedies about oversexed, impossibly attractive and curiously affectless teenagers who embrace life as a never-ending, omnisexual fuckfest. It’s a feature-length exercise in maddening artistic regression. The plot, such as it is, involves Thomas Dekker, an impossibly handsome pretty boy who looks like the lost love child of Jonathon Schaech and Adam Scott, fucking everything that moves while stumbling deeper and deeper into a bizarre secret world beyond his understanding.

Kaboom features all the nudity, non-stop fornication and bitchy one-liners that have made Araki a widely tolerated fixture in independent film circles before going all Southland Tales with Phillip K. Dick-meets-Gossip Girls subplots involving a mysterious cult, teen hedonists with superhuman powers, and various conspiracies, but these elements don’t raise the stakes so much as underline just how Araki seems to have invested in his overactive little sex freaks. And when Gregg fucking Araki seems to have tired of thinking up novel couplings for glorified American Apparel models to fuck each other’s brains out, something has gone seriously awry. (C-)

The Redemption Of General Butt Naked: How do you say you’re sorry to someone whose legs you shot, then sequestered in a bathroom for a week? How do you make amends to a fragile young woman whose brother you killed? How do you redeem yourself when you’re on record as being responsible for the brutal deaths of 20,000 people? Those are some of the hopefully unique problems faced by Joshua Milton Blahyi, the subject of The Redemption Of General Butt Naked.

At the height of the Liberian Civil War, Bhahvi, who was more commonly known as General Butt Naked due to, well, his aversion to wearing clothes while fighting, terrorized the Liberian populace with his psychotically committed brigades of child soldiers, decimating its population and leaving an endless trail of death and destruction in his wake. After a religious epiphany, however, Blahyi turned his life around and reinvented himself as an evangelist spreading a gospel of forgiveness. But can a man who has committed such atrocities ever be forgiven? Should he ever be forgiven? The Redemption Of Butt Naked follows its charismatic subject on one of the strangest, darkest goodwill tours of all time, as he travels around the country he once menaced apologizing profusely for killing so many people and asking for forgiveness.

In his transformation from butcher to preacher, Blahvi simply traded in one form of extremism for another; like all evangelists, Blahvi’s banter has the disquieting feel of spin and propaganda; we never really seem to get to know the real Blahvi, just the paper saint and gothic monster. Late in the film, a clear-eyed soul says that like everyone, Blahvi in his current form is about 75 percent good and 25 percent bad—so is this compelling but oddly distant cinematic portrait of a man trying to shake a past he can never outrun. (B)