National Lampoon biopic A Futile And Stupid Gesture laughs at and with Doug Kenney

Doug Kenney’s life was practically made for a movie. As a Midwestern kid carrying a chip on his shoulder all the way to Harvard, Kenney and put-upon bestie Henry Beard channeled their abiding contempt for authority into the Harvard Lampoon and its nationally scaled big brother. Kenney went on to build the faux yearbook, radio program, and live show that would make up the Lampoon media empire, as well as co-write the scripts for anarchic anti-snob comedies Animal House and Caddyshack. Anyone who made teenagers laugh during the latter half of the ’70s was most likely pals with Kenney, if not directly reading his words. He played the sad clown all the while, masking a deep-seated inner pain with one-liners until he fell off of a Hawaiian cliff at 33. His eventful career, internal conflict, and love of cocaine mark him as a prime candidate for the silver-screen treatment, and that’s precisely the problem.

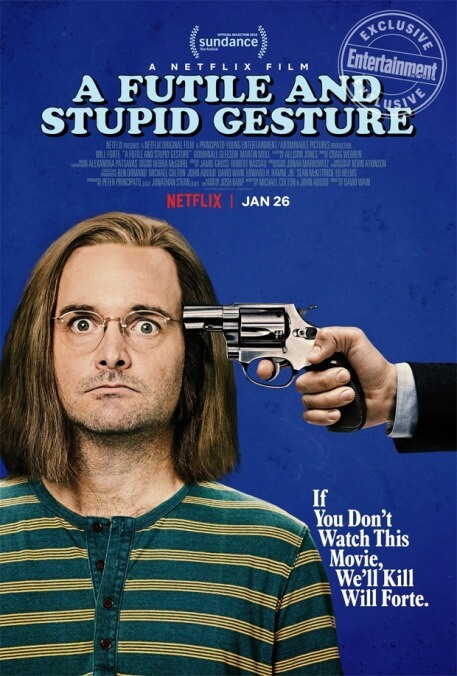

There’s a case to be made that the success of a biopic depends almost entirely on the director having studied Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story like a road map of cliché pitfalls to be avoided: Don’t lean so hard on formative childhood traumas, watch out for unnecessary framing devices, etc. To his credit, David Wain—of Wet Hot American Summer sainthood, and the director of the new Kenney tribute A Futile And Stupid Gesture—has most likely logged a few sit-downs with Dewey. An honest account of Kenney (Will Forte) building the National Lampoon brand and splitting from Beard (Domhnall Gleeson) must necessarily follow the well-worn “rapid rise, drug-fueled fall” template of the troubled-genius narrative, so Wain and his well-stocked cast do what they can to puncture the genre and let out some of its hot air. In a non-diegetic opening, an offscreen Wain feeds an imagined older Kenney (Martin Mull) corny lines about having changed comedy without being able to change… himself. Kenney, rightly, entreats his unseen director to blow him.

Wain shares in the savvy viewer’s exasperation with this particular strain of self-importance, peppering the film with similar implied eye-rolls at the unavoidable seriousness of Kenney’s story. He calibrates the hagiographic slobbering, conceding that National Lampoon was at least partially conceived as an opportunity to ogle models and that Kenney was an unreliable, unfaithful husband. The tone patterns itself after Kenney’s unstable internal state, with interludes of depression quickly giving way to the hectic fun of egomania. The script speeds by the premature death of Kenney’s golden-boy brother as fast as it can, point-blank apologizing for harshing the vibe, though not before one utterance of “The wrong kid died!” nearly verbatim. Like Forte’s Kenney, screaming from beyond the grave at the attendees of his own funeral to lighten up and laugh, Wain appears pathologically opposed to the maudlin. (Setting aside the final scene, which isn’t quite sure whether it’s needle-dropping “Beautiful Dreamer” ironically or not.)

But excising the goopy stuff is only half of the job. While Wain has developed an immunity to the biopic’s blustery pretension, he’s not so wary of the form’s more superficial shortcomings. While pretty consistently amusing, the film still suffers from a chronic case of Wikipediitis, recreating Kenney’s bullet-point moments as substitution for original wit or drama. Someone who knows nothing of the Lampooniverse may crack up at the bottomless cheerleader photoshoot and the classic gun-to-the-dog’s-head gag. More familiar viewers may wonder about the purpose of introducing Gilda Radner while giving her barely any lines, her very presence reduced to an Easter egg for entry-level comedy geeks.

Self-aware to the bitter end, Wain does evince a healthy discomfort with the artifice of the biopic. He will be the first one to admit that no one in the cast resembles their characters, but also that he doesn’t really care, and why should we? (If it worked for Todd Haynes in I’m Not There…) He also makes a pass at contextualizing the racism of the early Lampoon in one meta-bit featuring SNL player Chris Redd, a choice rendered somewhat ironic by Kenney’s abiding contempt for the show that stole his friends and material. In the most inspired joke not taken from Kenney’s playbook, a quick scroll across the screen lists all of the creative liberties taken with the material for the sake of organization and entertainment. But even while Wain chafes at some elements of fakery, others slip right by.

A sad story resistant to its own sadness, a meta-biopic gleefully subverting some overdrawn tropes and playing others completely straight, A Futile And Stupid Gesture is at odds with itself. Because Kenney and his deadpan cohort were so constantly messing with one another, they’re usually tripped up when one of them yields to a moment of sincerity. To echo the question asked on two such occasions, when one participant in an improv exercise can’t quite follow what the other wants: What’s the bit?