Neither Charlton Heston’s “cold, dead hands” nor his films get their due in a new biography

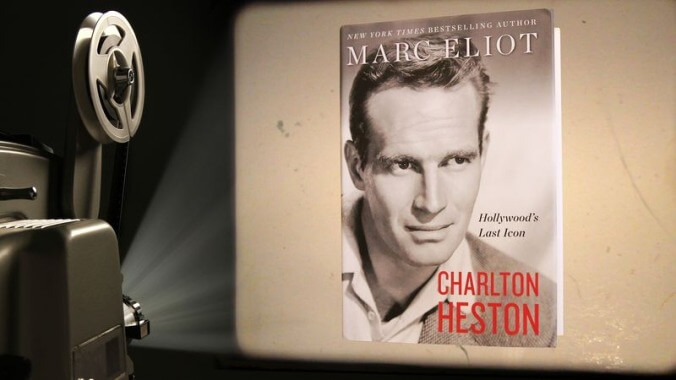

In the opening lines of Charlton Heston: Hollywood’s Last Icon, the biographer Marc Eliot references the notorious moment when Heston, the movie-star-turned-NRA president, thundered that the government could take his rifle “from my cold, dead hands.” Starting here is a plea on Eliot’s part. “There was so much more to Heston’s life than a single exclamation,” he writes. The episode “does not, by any stretch of the imagination, define who Charlton Heston was, all that he had accomplished in his extraordinary life, what made him tick as an artist and drove him as a man.”

Eliot is right that no life can be fairly reduced to a single moment (though surely anyone reading a Heston biography is aware the man was more than just those five words). But Icon fails to deliver the kind of complex portrait that intro promises. The book’s subject is a hugely important figure, but Eliot mostly avoids the things that make Heston historically notable. And what he does cover, he offers a surface-level look, brushing past contradictions and offering irrelevant tidbits instead of meaningful insights.

Despite the book’s subtitle, the thesis of which isn’t really explored or argued for, have any of Hollywood’s biggest stars retained less of a fan base than Heston? He’s hardly obscure, but now he’s mostly known for biblical epics, a genre that’s fallen out of favor; Planet Of The Apes and Soylent Green, still watched but decidedly camp; and Touch Of Evil, a masterpiece where his casting (as a Mexican man) is widely seen as the film’s biggest flaw. Unique among screen icons, he’s more interesting for his politics than his work or “story,” which presents obvious hurdles for a biography. His personal life seemed blissfully devoid of drama; he married young and happily (and was surprisingly shy growing up, faking a girlfriend by wearing a bracelet with a made-up girl’s initials on it), and he played it safe with the movies he made. Knowing that audiences liked him in heroic roles and historical epics, he gravitated toward those until he aged out of them, with a few excursions to the stage to play the same roles on multiple occasions. While undeniably charismatic, and able to command attention on huge canvases (something you can’t say of more nuanced actors), he lacked the kind of big personality that typified such collaborators as DeMille and Welles. He was such a square, Eliot quotes someone as saying, that he could’ve fallen out of a cubic womb.

This lack of conflict would be tricky for any writer, but Eliot too obviously stretches for drama, trying to make points land in the moment at the expense of a more cohesive take. At one point, noting a tapering of Heston’s popularity, he writes that, “A descending career line after relatively early success is not unusual in Hollywood… diminishing returns is the norm in an industry where youth is its most sellable commodity.” Ten pages later, the hit Midway “helped reaffirm [Heston’s] place in Hollywood’s hierarchy of stars with staying power.” He argues that Heston lost parts because of his right-wing beliefs, while at the same time noting he was too old to play them, while also mentioning the lifetime achievement awards he was being honored with.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.