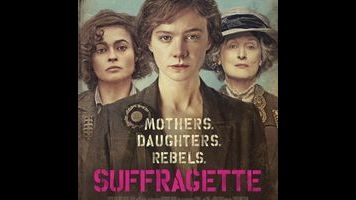

Many prestige pictures released by Focus Features look like they take place in overcast London, even if they don’t. So Suffragette, set in 1912 London during the women’s suffrage movement, has full license and reason to bathe itself in that drab Focus palette, full of pale blues and blackish browns. On its own, this decision makes sense; it’s an easy period shortcut to provide atmosphere for a very serious movie. And seriousness, it turns out, is the main card Suffragette has in its hand. It depicts an important movement that remains relevant today as a historical obligation of a movie, dutiful and often surprisingly dull.

Part of that surprise comes from watching Carey Mulligan muddle her way through the dullness. She’s played characters chafing against society’s expectation that they do just that (especially in An Education), and tends to anchor movies with a restless, sometimes sad-eyed intelligence. Here, the material never really brings Maud Watts, a young wife, mother, and factory worker who awakens to the suffrage movement, fully to life as a character. This leaves Mulligan depending on her watchful, half-lidded gaze; the movie has lots of scenes of her noticing stuff as she goes through familiar steps of radicalization. As she cycles through skepticism, growing interest, conflicts with a family that won’t support her, and a full commitment to the cause, Maud makes an empathetic set of eyes through which to observe the action. But the movie’s story doesn’t really take her anywhere further than the cause. Rather than deepening, she becomes more of a stand-in as the movie progresses.

This flatness doesn’t smooth out all of the film’s emotion. The estrangement of Maud from her flummoxed husband (Ben Whishaw, swallowing his charisma) and her loving young son (Adam Michael Dodd) is heartbreaking and unsparing, and supporting characters like movement leader Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham Carter) and weary peacekeeper Inspector Steed (Brendan Gleeson) draw passing interest that could easily turn into real engagement. The problem is that director Sarah Gavron and screenwriter Abi Morgan (a practiced hand at English history after The Iron Lady) haven’t shaped these characters and situations into a working movie. There are beginnings of one in the antagonism between Maud and Steed, who strategizes with other law-enforcement men, seen developing surveillance photos like they’re tracking a crime syndicate. The campaign against these women—the workaday mechanics of societal oppression—is interesting, especially as the relatively green Maud becomes more involved, and Steed pleads with her to be reasonable (which is to say, more docile and passive in her activism).

Eventually, the filmmakers locate the story of a woman improvising her way through revolution, set against a man who preaches law and nonviolence but enforces the status quo—but only after an hour-plus of table-setting, and without much payoff. (The movie’s big climax again features Maud more or less watching as important stuff happens.) As early as its opening sequence, Suffragette pauses to explain in on-screen text what’s going on: Women in England are beginning to use civil disobedience to agitate for the right to vote. Scant minutes in, the film is already calling its shots, telling the audience what’s so important about itself, rather than trusting them to understand it. The relationships between these women should do that work instead, and generally don’t. Their common ground includes feeling mutually starstruck by Meryl Streep—er, Emmeline Pankhurst, the legendary activist whose embodiment by the legendary Streep is so brief (under five minutes of screen time) that the movie seems to be either playing an unnecessary metatextual game (making Pankhurst into a de facto movie star) or performing an experiment to determine just how little Streep has to do in a movie to receive an Oscar nomination.

It’s easy to see why the movie might expect awards, even if they don’t pan out. Suffragette is utterly respectful, even borderline gritty in its street-level depictions of activism. At times, it does a concise job of conveying specific frustrations, as in the scenes where the women are “allowed” to speak their piece to lawmakers, only to be roundly ignored—a condescending bit of token attention that stings almost as sharply as more direct oppressions. But the ideas behind these moments remain more memorable than the staging of the scenes themselves, and the dreary look and handheld camera intended to stress its realism only register as generic movie-ness. Mulligan isn’t the only stand-in; the whole movie comes across as a placeholder, the best that could be done at the moment. Despite a top-shelf cast and strong subject matter, Suffragette feels like the product of limitations.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.