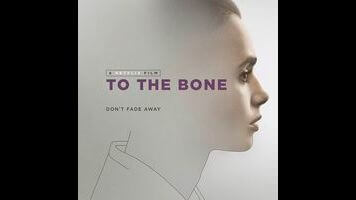

Anorexia is one of those subjects that seem tailor-made for a medium as darkly fascinated by bodies and self-destructive obsessions as film, and yet it always comes across as phony, simply because actors can never really look anorexic; thin and baggy-eyed is a long way from the sight of skin sucked so tightly over bones that it appears that a person’s body might crumple in on itself at any moment. That doesn’t mean that movies can’t tackle the psychology, but with only a few exceptions (e.g., the English writer-director Mike Leigh’s 1990 film Life Is Sweet, which depicts a young, working-class bulimic woman), films about eating disorders take the form of hokey, know-the-symptoms public service pamphlets aimed at teens. There’s a reason why the topic is popularly associated with cheesy TV movies. The Netflix-produced To The Bone, which was written and directed by TV veteran Marti Noxon (UnREAL, Girlfriends’ Guide To Divorce), isn’t going to change that perception. It’s snarkier and a little more self-conscious than the rest, but just as cornball.

Lily Collins stars as Ellen, a 20-year-old, internet-famous anorexic artist from a well-to-do Los Angeles family who agrees to move into a group-home-style treatment center for young people with eating disorders run by the no-bullshit Dr. Beckham (Keanu Reeves). We know Ellen has an attitude problem, because she smokes cigarettes and is introduced bailing on the latest in a string of in-patient clinics by informing her therapy group to “suck my skinny balls”; and we know she doesn’t like her prissy, Southern-accented stepmom, Susan (Carrie Preston), because she rolls her eyes when the family’s plastic-surgery-addicted maid refers to Susan as her mother. (To The Bone takes place in one of those alternate universes where no one seems to grasp the concept of step-parenthood.) With the exception of her beloved stepsister, Kelly (Liana Liberato), Ellen is surrounded by grotesques: the maid; Susan; the other patients at her last treatment facility; her unseen father; even her hippie-dippie lesbian mom (Lili Taylor), who came out when Ellen was 13.

So perhaps Dr. Beckham, who speaks in Reeves’ usual relaxation-tape cadence, just seems like a breath of fresh air, even if moving into the group home means sharing the dinner table with a new cast of broadly defined single-issue characters: the pregnant one; the bulimic one who stashes her vomit; the English, anorexic, ballet-dancing love interest (Broadway actor Alex Sharp, making his film debut), whose adorable retro sensibilities are represented by a bedroom decorated with a picture of Frank Sinatra and a poster that just says “Jazz Festival.” Noxon is an unremarkable, at times clumsy director with no sense of staging, but she has decent taste in attractive young actors—which, however, only adds to the bogusness of the movie’s conception of illness, treatment, and family, and spoils whatever point To The Bone might have to make. It’s only in retrospect that one starts to notice how little the movie actually addresses Ellen’s condition; somewhere in trying to externalize a character’s problems through corny and ham-fisted subplots, it loses her altogether. All that’s left is a body hung in chic, loose clothes and a pretty face framed by dark caterpillar brows.