Netflix’s twisty sci-fi thriller I Am Mother has a lot on its mainframe

It takes guts to make a science-fiction/horror film that visually recalls Alien and name its repository of artificial intelligence “Mother.” (Technically, the Nostromo’s computer, voiced by Helen Horton, is the MU-TH-UR 6000.) In this particular case, however, that choice isn’t just a cute homage. I Am Mother’s title character may be a robot, but she’s also genuinely a parent—perhaps the last one on Earth. Opening text informs us that the cavernous, futuristically high-tech building in which most of the film will take place is a repopulation facility, and that it’s been just one day since some unspecified “extinction event;” the facility houses 63,000 human embryos, with which this single robot, Mother (who’s physically performed by Luke Hawker but speaks in the warm yet slightly mechanical voice of Rose Byrne), will ensure that Homo sapiens lives on despite whatever cataclysm happened outside its ultra-thick, reinforced walls.

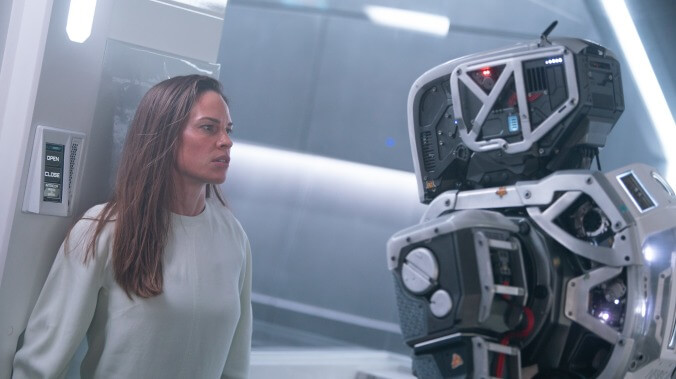

Initially, though, she grows only one infant, who she calls simply Daughter (briefly seen as a small child, but primarily embodied at roughly age 20 by Clara Rugaard). It’s not entirely clear why the repopulation effort is going so slowly—Mother explains at one point that she must learn how to care for one child before creating others, but that starts to seem less plausible once Daughter is nearly old enough to drink (were there still any bars). Another vaguely suspicious aspect of their life together involves Daughter’s education, which seems rather heavy on difficult ethical/philosophical questions and culminates in an ostensible exam that resembles the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. In any case, the true test comes when Daughter hears someone banging on one of the facility’s doors, and finds a woman (Hilary Swank) who’s been shot in the abdomen—by a robot exactly like Mother, she claims. Since Mother has always maintained that nobody outside the facility survived, the very existence of another human being is itself a shock, and Daughter decides not only to let the woman in but to keep her hidden.

That isn’t I Am Mother’s only secret, by a long shot. This impressively ambitious first feature, directed by Grant Sputore and written by Michael Lloyd Green (from a story that he and Sputore jointly conceived), has more than one agenda, and doesn’t quite succeed in making them cohere. On one level, it’s an allegory about everyday parenting, creating an extreme variation on the tumultuous moment when every child has to assert her independence and become an autonomous adult. On another level, though, it’s about the potential dangers of creating a fully conscious machine—even one that’s been carefully programmed to make saving human lives its utmost priority. Those two themes aren’t mutually exclusive, but Sputore and Green work hard to keep one of them murky for as long as possible (though anyone who pays attention to certain details and can do basic math will realize early on that something’s up); while that creates suspense, it also undermines what should be the ending’s cathartic power. So many truly disturbing revelations pile up in the final half hour or so that processing the relevant information leaves little time for raw emotion. Swank’s nameless character, in particular, remains a pencil sketch.

Still, there’s no question that Sputore can direct a movie. I Am Mother (which premiered at Sundance earlier this year and was snapped up by Netflix) can’t have had much of a budget, by sci-fi standards, and it does look a tad chintzy when it eventually moves outside. The repopulation facility, however, has been richly imagined by production designer Hugh Bateup, who’s worked extensively with the Wachowskis (going back to The Matrix, on which he served as art director—basically the production designer’s second-in-command) and here finds novel ways to make the immaculate look sinister. And Mother herself is a remarkable creation, both in appearance (she actually looks strangely like Emmet from the Lego Movies: a conglomeration of rounded rectangles capped with two beady round eyes, which swivel on tight arcs to fashion expressions) and in movement (a combination of graceful and lumbering that likely couldn’t be achieved via digital effects). Rugaard, a relative newcomer who previously played a supporting role in Teen Spirit, is the sole (visible) human onscreen for much of the film, and has strong natural presence, though Daughter never really seems as if she’s lived her entire life with just a humanoid robot for company (plus clips from the Carson-era Tonight Show, for some reason). The film just has too much other stuff going on to delve into what it’d be like growing up as the first and so far only member of Humanity 2.0. That’s a failing, but an eminently forgivable one. Far better to have too many heady ideas than too few.