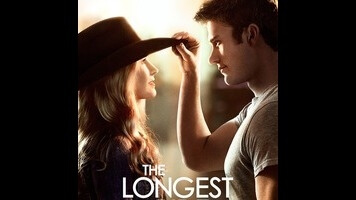

Nicholas Sparks takes one step forward, one step back with The Longest Ride

It rains four times during The Longest Ride’s two-plus hours. Rain is not an unusual occurrence for a movie based on a book by wealthy sentiment-peddler Nicholas Sparks, but while Ride does use the weather to heighten both melodrama and romance, the downpour never serves as a direct backdrop for a passionate clinch or a tearful reunion. The movie contains other items from the Sparks checklist—handwritten letters, soldiers, paeans to the romantic majesty of coastal North Carolina, death—but doesn’t milk all of those for maximum shamelessness, either. In this restraint, it shows the mildest hints of maturity in what has become a de facto franchise.

For example, the movie doesn’t insist on giving Luke (gristle-free Clint Eastwood substitute Scott Eastwood), its contemporary romantic hero, a particularly honorable or heroic profession. Instead, he’s just a bull rider, albeit one of the best damn bull riders in the world, and one so honorably “old school” that he doesn’t believe in women buying him a drink or calling him first. The woman in question is Sophia (Britt Robertson), a smart and sensible college senior who makes a suspiciously quick transformation from utter disinterest in sorority-cowgirl affectation to paying keen attention to the sexy, high-stakes world of bull riding. She also loves art, as she explains: “I love art. I love everything about it.”

Luke and Sophia may have mismatched backgrounds and unequal levels of art love, but they don’t have any reason to handwrite romantic letters to each other, which is probably why they happen upon a car crash and rescue Ira Levinson (Alan Alda), box of love letters in tow. As Sophia runs into relationship trouble with Luke, she visits Ira in the hospital and reads the letters with him, leading to flashbacks that follow a younger Ira (Jack Huston) and his beloved wife Ruth (Oona Chaplin) as they navigate their own troubles in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s.

Director George Tillman Jr. doesn’t integrate the two stories particularly well. The flashbacks always leave off at a crucial narrative juncture, but the movie rarely shows present-day Ira halting his story—few of the scenes between Alda and Robertson have endings at all. Their entire relationship exists primarily to deliver those flashbacks and draw tenuous parallels between the two couples. (“Ruth also loved art,” Ira excitedly notes, not mentioning if she also enjoyed other equally obscure concepts, such as food or sunny days.) Inelegant transitions abound even when the movie sticks to the present, where the fated Luke and Sophia have awkward, faux-flirty conversations. The movie manages to generate some heat between its young leads in exactly one effective sequence that cuts together Luke’s professional bull-riding, Sophia’s attempt to ride a practice rig, and the couple having sex constantly. Even then, they seem to like each other because they both look good semi-naked.

Back in the past, though, Huston and Chaplin show hints of timeless charm, enlivening the material not unlike the way Rachel McAdams and Ryan Gosling almost sold the hokum of The Notebook. The movie draws Ira and Ruth’s story out too long, but in its broad way it actually addresses the bumpiness of a long-term relationship, rather than tearing its lovers apart via war, disapproving parents, or bad luck (though it does touch upon two of those three). Even the sketchily developed art business that supposedly connects Ruth and Sophia is a welcome respite from Sparks’ usual vague churchiness.

The relative decency of the flashback material only makes Sophia and Luke’s big conflict—he wants to keep riding bulls even though an old head injury threatens his life—look sillier. Bull riding comes across as such a comically stupid endeavor that attempts to equate it with anything in Ira’s narrative feel muddled at best, especially when the movie tries to wring suspense from Luke’s confrontation with his greatest enemy: the villainous bull that threw him off and gave him his head injury in the first place.

In other romances, this would be crazy ridiculous, but it’s only low-level nutty for Sparks. (Despite the varying screenplay and directing credits, the author—who has begun producing the adaptations of his work—is the true auteur at work in this unofficial series). Despite undermining its own better qualities, The Longest Ride still qualifies as one of the best Sparks films by virtue of not including any love-ghosts or destructive misinformation about how Alzheimer’s works. It doesn’t jumble all that rain, letter-writing, and North Carolina scenery into something new or even very good, but it has its fleeting moments of low-key likability.