Nick Cave returns with a reason to keep on living: 5 new releases we love

There’s a lot of music out there. To help you cut through all the noise, every week The A.V. Club is rounding up A-Sides, five recent releases we think are worth your time. You can listen to these and more on our Spotify playlist, and if you like what you hear, we encourage you to purchase featured artists’ music directly at the links provided below. Unless otherwise noted, all releases are now available.

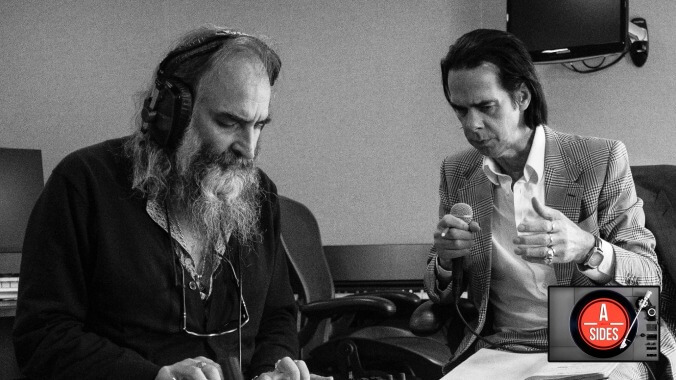

Nick Cave And Warren Ellis, Carnage

[Goliath Records]

It’s no surprise to discover just how heavy and somber Carnage is. Nick Cave and Warren Ellis have written together many times at this point—as bandmates in The Bad Seeds and Grinderman, and also as composers on more than a dozen soundtracks. But in their first official release as a duo, the pair find an awe-filled beauty in the both the minutiae of the everyday and the immensity of existence, with Cave’s lyrical attention roaming from the distance of the fading night sky to the inevitable dissolution of our bodies, an “ice sculpture melting in the sun.” Musically, this feels like the logical next step on their artistic journey: Fans of Ghosteen, Cave’s 2019 magnum opus of lamentation and hope, will find Carnage in part a continuation of that classically arranged (and surprisingly accessible) work. Atmospheric swells surrounding Cave’s piano (synths, strings, and more envelop his stately chords) and lyrics both singularly cracked (“With my elephant gun and tears, I’ll shoot you all for free,” the narrator of “White Elephant” proclaims) and almost fey in their simplistic purity (album closer “Balcony Man” repeats, “This morning is amazing, and so are you” with steadily increasing fervor). But there are also pulsing synth rhythms that at times conjure a spare, almost ambient version of Grinderman music, reminiscent of some of Mark Lanegan’s solo work. And the aforementioned “White Elephant” nearly seethes with spoken-word intensity and a Massive Attack-like beat, before erupting into an uplifting choir, transforming that rage-filled grief into revivalist redemption. This eight-song collection is a moving, transportive meditation on what comes after—after grief, after life, after love—and finds reasons to keep going. [Alex McLevy]

Julien Baker, Little Oblivions

[Matador Records]

“In many ways, Little Oblivions is a re-introduction to Baker’s music. Both of her previous records focused on a soft, minimalist sound that highlighted Baker’s powerful voice and words. It’s the kind of music that is best listened to alone. Even her live shows replicate those records’ intimacy; a cough from an audience member is enough to distract from Baker’s performance. But Little Oblivions takes on a heavier sound reminiscent of her time in Forrister and The Star Killers. It’s a version of Baker—one that carries emo and pop-punk roots—that many are not familiar with. The introduction of drums and synths feels appropriate for this record, as they intensify the emotion of the lyrics. Lead single ‘Faith Healer’ gives the sensation of being on a carnival ride; the tempo change is thrilling, with the synths unexpectedly dominating the song. It matches the intensity of Baker’s lyrics, as she notes that she knows relapsing will be harmful, but she misses the high substances give her.”

Read our featured review of Little Oblivions here.

Lydia Luce, Dark River

[Self-released]

Lydia Luce explores and expands the boundaries of the Nashville sound on her latest, Dark River. Using celebrated game-changers like Dusty Springfield, Emmylou Harris, and Neko Case as jumping-off points, Luce’s self-released second album makes exhilarating use of layered instrumentation for a genre-bending sound that flits between chamber pop, country-rock, and singer-songwriter balladry. Pillowy postwar strings are especially prominent, which should come as no surprise: Along with leading her own band, Luce is also a well-known violin session player. But although the album is stuffed full of sound, there’s still a lonesome quality to Luce’s melodies that roots Dark River in the world of country and western. No matter the genre, however, two things remain constant: the soft edges of Luce’s voice, and the swelling dynamics that give the title track its wings. [Katie Rife]

McKinley Dixon, “Make A Poet Black”

[Spacebomb Records]

Wordsmith McKinley Dixon established himself as a lyricist to watch with his set of 2018 LPs The Importance Of Self Belief and Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?, infusing performance with wit and stark vulnerability. In preparation for his upcoming album For My Mama And Anyone Who Look Like Her, Dixon returns this month with “Make A Poet Black,” a theatrical culmination of grief and existential pondering. You won’t find snares or any of the percussion that often goes hand-in-hand with hip-hop; instead, tightly knitted verses ride on swelling strings and the forceful, looping pluck of the koto. Dixon takes his time exploring not only his own relationship with mourning—the song tracks his experience with the loss of a friend—but how Black people tend to process their own trauma, which often involves a sense of labor. In his own words, Dixon questions, “What about trauma forces a Black person to feel the need to create?” It’s a query worth both thoughtful reflection and this seriously artful rhapsody. [Shannon Miller]

Blanck Mass, In Ferneaux

[Sacred Bones]

There are exactly two tracks on In Ferneaux, the searching and complex new album from Blanck Mass, a.k.a. electronic music provocateur Benjamin John Power. “Phase I” and “Phase II” are vague, simple names that hide multitudes—a fitting assemblage for an album that literally moves from our innermost thoughts to the distant stars. Thematically meant to evoke the nigh-inexplicable connections we make with others—other people, other places, other times—these twin movements are littered with the incidental sounds of voices and nature compiled from years’ worth of Power’s field recordings archives. Synths pull back to reveal boats creaking against a dock; the pummeling noise that opens “Phase II” drops out to spend minutes listening in on various men opening up about deeply intimate thoughts. Sonically, it’s a less assaultive journey than 2019’s Animated Violence Mild, though the shift in tone actually makes the harder-hitting moments that much fiercer, as in the aggressive drums that erupt almost five minutes into “Phase I,” or the white-noise sheen that irradiates the first half of “Phase II.” But through it all, Power’s restless, experimental muse finds beauty in the connection of the organic and inorganic, the painstakingly composed and the accidentally captured. If there’s such a thing as the opposite of easy listening, this is it. [Alex McLevy]