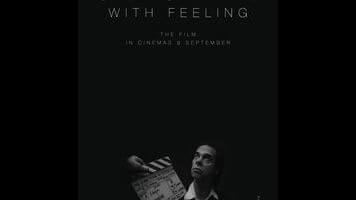

Nick Cave’s One More Time With Feeling is an intimate but not invasive portrait of grief

“I don’t believe in narrative anymore… I don’t think life is a story,” Nick Cave says early in Andrew Dominik’s documentary One More Time With Feeling. He’s explaining—haltingly yet articulately, as he does throughout—the reasons why the songs he’s written lately have taken a turn toward the abstractly expressive, away from the precisely realized murder ballads and apocalyptic love songs for which he’s known. His songs no longer follow any linear sense or strive for satisfying resolution, Cave says, because life doesn’t work that way. And even though the director interjects to disagree, his film doesn’t strive to tell a story either. Rather it’s a loose assemblage of studio vignettes, interviews, and poetic musings structured around the completion of The Bad Seeds’ 16th album, The Skeleton Tree, one that’s often deliberately ramshackle in its fumbling improvisations and inclusion of equipment malfunctions—not to mention Cave’s frequent commentary on the camera’s presence. As a documentary, One More Time hesitates to say anything too neatly or directly. In that way, it is a uniquely effective meditation on grief.

There is a story here, albeit one Cave is, quite understandably, not eager to tell. Cave’s 15-year-old son Arthur died midway through Skeleton Tree’s production, falling from a cliff near their family home in Brighton, England, after taking LSD. Cave’s efforts to move past such a devastating loss, along with his attempts to redouble his conviction that “the records go on and the work goes on,” forms the underlying tragedy of One More Time, even as Arthur’s name isn’t spoken aloud for more than an hour. Instead, Dominik, who previously collaborated with Cave on The Assassination Of Jesse James By The Coward Robert Ford, allows the musician to talk around his pain, the way any true friend would. (In fact, the film was conceived as a way for Cave to avoid the more direct inquiries of a press tour.) Nevertheless, Arthur is always there, haunting every interview, where Cave talks vaguely of the unspecified “trauma” that’s sapped him of his creativity, and felt deeply in every song, whose mournful ruminations Cave hesitatingly acknowledges could be seen to foretell “certain events.”

That could be applied to a lot of Nick Cave lyrics, honestly, and even he dismisses the idea that Skeleton Tree, which was written before Arthur’s accident, is directly about his death. Still, when the very next scene finds Cave singing “Jesus Alone,” pushing his way through its opening line, “You fell from the sky, crash-landed in a field near the River Adur,” it’s impossible not to make the connection. Likewise, when Cave groans in voice-over, “This is really fucking difficult,” he’s grousing about the need to overdub a vocal track, but its deeper meaning is obvious. Every song he sings from now on—everything he does—feels suffused with mourning.

But there’s another subtext as well, one that may have colored the film even without those horrible events: These days, Cave is also grappling with living up to the myth of himself. No one—not Cave, not his bandmate/bedrock Warren Ellis, not even Dominik—are comfortable talking about Cave’s personal life in any respect, because Nick Cave has never seemed like a person. On stage and on record, he’s always played the debonair devil, clad in natty black suits, boasting eyebrows like batwings, and growling portentously of biblical plagues, yet here he seems shockingly, fragilely human. “You decay and you diminish,” he declares. Looking at footage of his newly baggy eyes, he asks, “What the fuck happened to my face?” At one particularly unnerving point, Cave wears a tracksuit. Meanwhile, the sympathy being accorded to him, all that eggshell-stepping from even strangers on the street, has only made him feel weaker. “When did I become an object of pity?” he asks incredulously.

Fortunately, Dominik’s film never makes him one. Instead, it’s characterized by a sense of tiptoeing caution and respectful space—particularly in scenes where Cave interacts with his wife, Susie Bick, and Arthur’s surviving twin, Earl, and their tenderness toward one another shines through without ever feeling like it’s being exploited for sentiment. When Bick finally does say Arthur’s name aloud in the film’s most heart-wrenching scene, the camera doesn’t push in on her watering eyes but rather hangs back politely. The audience is kept at a distance that allows it to feel the family’s suffering without making it complicit in dredging it up.

It might be confusing, then, that One More Time is shot mostly in the in-your-face medium of 3-D. It’s especially questionable given the fact that so much of it takes place in studios, taxicabs, hotel rooms, and other claustrophobic spaces—all rendered in ashen black and white, save for one revelatory color sequence set to “Distant Sky.” But the effect creates a surprising intimacy, even as it holds the viewer at arm’s length. And the dreamlike bent it lends to Dominik’s occasional, unexpected camera swoops and cinematographer Benoît Debie’s starkly pretty compositions only reinforces that idea of the surreal, fragmented nature of a life, so unthinkably interrupted, struggling to go on.

As with life itself, there’s no tidy resolution to be found here—no climactic scene of Cave walking out before a sold-out theater to rip-roar through “From Her To Eternity,” healed at last by the power of music. The closest it comes is letting Cave finally stand up from the piano to conduct his band with just the barest hint of his gunslinger swagger. And like grief, the constant sadness starts to feel repetitive, the elusiveness of a happy denouement frustrating. But anything else wouldn’t have been the truth. One More Time is a complex portrait of a man climbing his way out from tragedy while coming to terms with his own vulnerability—a poignant image, especially in a year where we’ve felt the loss of so many of Cave’s fellow immortals. “They told us our dreams would outlive us / They told us our gods would outlive us, but they lied,” Cave sings near the film’s close, a tune that is as bleak yet beautiful, as heartbreaking yet hopeful as everything that preceded it. Life is not a story, the movie says, but in many ways it is a Nick Cave song.