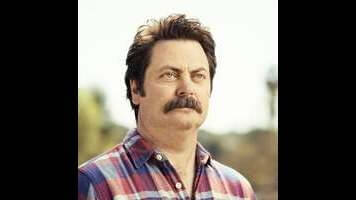

Nick Offerman is at his best detailing modern-day Gumption

In chapter 11 of Gumption, Nick Offerman handily refutes the idea that Yoko Ono was responsible for the breakup of The Beatles. He also espouses her creativity as an artist, recounts the gallery exhibition at which John Lennon connected with her work, and delves into the cleverness of their peace efforts. The chapter is not only indicative of what Offerman tries to accomplish throughout Gumption—dispel long-held myths, muse on anecdotes about the “gutsiest troublemakers” who have died, and exchange philosophies with many troublemakers still alive—but is also the point where he hits his stride.

Gumption, Offerman’s second literary offering, declares its intention in the subtitle to “relight the torch of freedom” with the help of 21 people, from Freemasons to idealists to makers. The first seven chapters—featuring the likes of Benjamin Franklin, Frederick Douglass, and Eleanor Roosevelt—read like Offerman consumed countless books about these historical figures, recalled the highlights in his singular voice, then took a step back to examine what they mean to him personally and what lessons they may impart to the modern audience.

Those historical figures also serve to add a level of prestige to the already impressive cast of characters that follows, including actor Carol Burnett, musician Jeff Tweedy, and toolmaker Thomas Lie-Nielsen. Famous as they may be in their respective fields, including them among the likes of James Madison and Frederick Law Olmsted furthers the notion that there are people in our midst who, one day, may be remembered the same way we remember forebearers.

Gumption takes off when Offerman gets into those latter chapters, in large part because he has the chance to meet many of his heroes. The fascination does not simply end, however, at celebrity meeting celebrity—the readers are privy to the conversations. Gumption offers something more. Offerman refrains from simply recounting his encounters chapter to chapter. Rather, he uses these figures and accounts to help build his message.

Though the book is officially classified as humor, it is much less an exercise in cracking jokes than examining the socio-political landscape (both historical and contemporary) of the United States, from racial and gender inequality to technology and lifestyle to religion. Though it does provide some chuckles, it’s preachy at times. While Offerman takes TV personalities from both side of the aisle—Fox News to Jon Stewart—to task for oversimplifying and essentially toeing party lines, Gumption itself has its own self-righteous streak. Offerman presents his thoughts as common sense more than that of any political party, but he leaves little room for debate, and at times the book can read as though he found a bunch of like-minded individuals to have his back.

That said, the points Gumption tries to drive home are not without merit. And even while singing the praises of George Washington and Theodore Roosevelt, Offerman does not shy away from acknowledging shortcomings, especially when it comes to those of old white dudes (and younger ones, like himself). He repeatedly champions the tenets of feminism, extols the virtues of being a nonconformist, and makes pleas for less disposable consumerist culture. He’s not wrong. He’s just using a blunt instrument when a precision tool might be more effective.

The cover of Gumption—a remodeled Mount Rushmore—is a good image by which readers can judge what’s inside. The stated purpose of the book is to feature 21 American troublemakers, but in making himself part of their stories—in using his humor to lure readers into a book much more about social commentary, driven by an apparent desire to shake up the status quo—Offerman himself makes gutsy troublemaker number 22.