Nico, 1988 unflinchingly portrays the death of an icon

Nico largely endures in the popular imagination for her work with the Velvet Underground, an unhappy marriage arranged by Andy Warhol in part for the model’s aesthetic virtues, the contrast she cut against the scuzzy band. On 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico and the same year’s solo debut Chelsea Girl, she plays the part perfectly—icy and impassive and darkly enigmatic, her hollowed-out alto bringing to life songs by Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne, and others. They’re classic LPs, and Nico hated them; she wept upon hearing Chelsea Girl the first time. The next year, she began elucidating her own artistic vision with The Marble Index, the first in a trilogy of immaculately gloomy, glowing, and abrasive albums, full of dissonant drones and funereal dirges, that’d go on to inspire waves of goth, punk, and experimental musicians. In the ’80s, she dabbled in post-punk on the serpentine Drama Of Exile, and then embraced synthesizers on 1985’s Camera Obscura, her final album.

Nico, 1988 is obsessed with this divide in her work, both artistically and from the public’s perspective. “My life started after my experience with them,” Nico (Trine Dyrholm) chastises one eager interviewer early on. The film, despite its name, mostly takes place in 1986, a year after her final album, as an aging and deeply dissatisfied Nico—going by her birth name, Christa—makes her way through Europe on a late-career tour. There is no glamour here: She plays to half-empty rooms, sharing sleeping quarters with a band for which she has little professional respect. We see one bandmate dozing off mid-set, high on heroin; Nico, shooting up in bathrooms and dressing rooms, has the air of a professional user, soldiering on cogently enough afterward. She varies between curt and outright cold to the people around her, particularly her long-suffering lawyer (John Gordon Sinclair). The happiest we see her in the early stretch is slamming a bowl of spaghetti in the dead of night, stopping only to down a glass of limoncello. Later, after shooting up before a gig, she requests that her assistant (Karina Fernandez) fetch her another bottle of the after-dinner drink, then walks out to perform a glassy rendition of Nat King Cole’s “Nature Boy” to a politely disinterested dining room. The tour is a simulacrum for Nico’s career at that point: disordered, depraved, and unfairly overshadowed by her career-starting stint as Warhol’s designated femme fatale.

Writer and director Susanna Nicchiarelli seems interested in creating some sort of resolution for Nico before her death in 1988, an event which hangs over the entire film by dint of its title. Nicchiarelli intersperses the bleak travelogue with moments from the day of Nico’s fatal bicycle accident, grainy flashes of her swinging Factory heyday, and memories from her childhood wandering through bombed-out Berlin. It handles delicately the trauma the war instilled in her, mostly informing her suffocating pessimism. “I’ve been on the top, I’ve been on the bottom,” she says at one point. “Both are empty.” Music is no salve. She talks openly about quitting, and seems haunted by her failures as a mother. The desire to reunite with her estranged son, who is undergoing his own battle with addiction, provides the film’s central drive, but we move toward it slowly. The film, brief as it is, dwells in this unhappy space, drawing much of its power from it. This is a portrait of an unlikable woman producing difficult art to miserable ends, finding most of her happiness in the ways she no longer conforms to the image that made her famous.

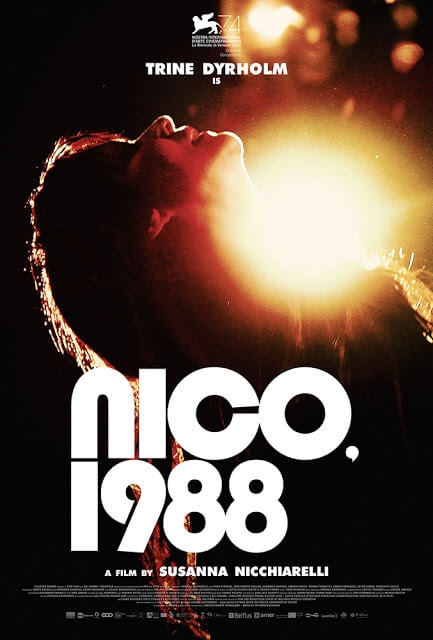

Like Gus Van Sant’s Last Days, Nico, 1988 is at its best in these liminal moments, its creation of a cognitive space to ponder an artist’s legacy, as well as literal spaces that reflect it: faded ballrooms, twilit monuments, bleary countrysides. Unlike that movie, though, Nico, 1988 occasionally succumbs to hoary biopic clichés, awkwardly imposing narrative beats. (There are a lot of contentious, didactic interviews.) Dyrholm captures Nico’s gradual reawakening, from fuck-everything nihilism to hard-won sentimentalism, with a raw and brave performance; she also, for what it’s worth, fucking nails Nico’s unearthly singing voice. But for a concert travelogue, the film has little interest in the actual concerts, settling repeatedly for a camera whirling counterclockwise around Dyrholm’s stomping, incantatory performances. It’s a strange but effective music biopic, delighting in the far end of fame and making a studious critical case for the artist’s later work that nevertheless lionizes the early stuff. “I think her music is hideous,” Nico’s much-abused assistant says at one point, watching a gig, and to the film’s credit, it doesn’t demand you agree or disagree. In that spirit, it’s as uncompromising as Nico herself.