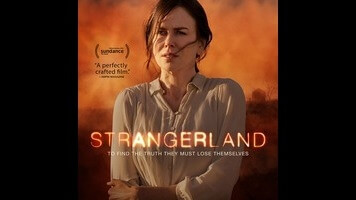

Nicole Kidman wants her kids back in the muddled mystery Strangerland

Once Hollywood actresses start to age out of love-interest roles (that is to say, when they turn 35), one particular option looms in their unfairly diminished choices: play a mother, especially one fighting tooth and nail for her child. This has worked out well enough for the steely determination of someone like Jodie Foster, but it’s proved less viable for the offbeat tastes of Nicole Kidman, whose few attempts to approximate a parental avenger (The Invasion) have been less convincing than her sadder or scarier versions of on-screen mothering (The Others; Stoker; Rabbit Hole). Kidman again approaches a parent role from a fresh angle in Strangerland, playing Catherine Parker, a woman whose teenage daughter Lily (Maddison Brown) and younger son Tommy (Nicholas Hamilton) have gone missing, possibly in the Australian desert.

Even without the trappings of a high-octane child-retrieval thriller, this could be a familiar part (the story has faint echoes of Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners, among other projects), but as ever, Kidman finds a wealth of complexity in her character. Catherine’s family has recently relocated to a small town in Australia; the reasons remain unspecified for a while, but it’s clear that Catherine and the kids don’t particularly like it, while Catherine’s irritable husband Matthew (Joseph Fiennes) considers the move a necessary inconvenience. Lily passes the time by cutting school and making eyes at locals, with Tommy forced to tag along as their dad admonishes him to watch over his older sister. It doesn’t do much good; early in the film, Lily proves easy enough to lure away from her brother with a simple “come with me,” issued by a garden-variety teenage dirtbag at a skate park. A few tense family arguments later, both children have disappeared into the night, and local cop David Rae (Hugo Weaving) is on the case.

In its first half, Strangerland works as a character-based procedural, even before a possible crime enters into the narrative. Kidman—appearing in her first Australia-set movie since, well, Australia—remains fearless, willing to both trade on her beauty and interrogate it ruthlessly, as she looks at her daughter with a mix of affection, helplessness, and even jealousy. When Lily disappears, Catherine performs a frantic re-evaluation of her life, and Kidman unravels with raw emotion. Fiennes has less room to maneuver, mostly playing up his character’s paranoia about his daughter’s sexuality and intimations that said sexuality is all Catherine’s fault: “She’s almost as out of control as you were,” he barks at one point. Even when the supporting characters falter, director Kim Farrant, making her fiction feature debut, offers a vibrant sense of place with the film’s rural setting. There’s plenty of the usual scorching sun and natural outback filth, including a heavy dust storm that coincides with Catherine’s initial panic over her children, but Farrant also includes interiors shot with heated-up colors. The green, pink, and blue hues that fill various rooms contrast with both the dusty browns of daylight and the shadows that fall over the town and desert at night.

After establishing its relationships, though, too much of Strangerland turns on characters withholding information, with little drama accompanying the corresponding revelations. Rae, for example, has a personal connection to the case that initially seems like an intriguing social wrinkle, but winds up only making the story feel insular and the small-town setting feel even smaller. Other background information hinges on Catherine’s discovery of Lily’s sort-of diary, the kind of impeccably detailed art-project journal that allows movie teenagers to express their innermost thoughts, secrets, and desires to design elaborate coffee table books. Strangerland makes a few ill-advised jumps into the fever-dream intensity of Lily’s book via some poetry-reading voice-over and dream visions, as it struggles to conceptualize a character who leaves the screen too early to receive much direct characterization.

Intentionally or not, Farrant and her screenwriters leave a hole at the center of their film. Its ambiguity, about character motivations and past secrets as well as the central question of where Lily and Tommy went, is both welcome (in the context of other missing-child dramas) and more than a little self-conscious (in the context of expertly detailed ambiguities like gold-standard Zodiac). Kidman clarifies as much as she can, and for a while the movie seems to be on her wavelength. Eventually, though, its mysteries get lost in the shadows.