Mort goes to the opposite extreme, focusing on the final years of Simone’s life—a period so uneventful that her fairly extensive Wikipedia bio completely ignores it. (Apart from a few flashbacks, Nina takes place entirely after 1995. She died in 2003 at 70.) Specifically, Nina dramatizes the relationship between Simone and Clifton Henderson (David Oyelowo), a nurse who first becomes her personal assistant and then her manager. Henderson was gay (though the film treats him more as asexual), so no romance developed between the two. Instead, Nina plays something like a non-comedic remake of Arthur, with Simone striving to stay as drunk as possible and generally misbehaving while poor beleaguered Hobson—sorry, Henderson—follows her around accepting her abuse with quiet dignity and making sure she doesn’t get herself into too much trouble. Eventually, he manages to organize a big comeback concert for her, and the world acknowledges her greatness.

On the one hand, this approach does avoid the musical biopic’s usual clichés, since it omits almost everything that a Nina Simone movie would ordinarily include. (A few scattered flashbacks to earlier points in her life appear at random intervals.) On the other hand, though, it seems almost willfully perverse to take one of the great African-American artists of the 20th century—the woman who wrote “Mississippi Goddam” in response to the murder of Medgar Evers—and depict her exclusively as a crazy drunken rich lady who needs to be looked after by a patient mannequin. Oyelowo is one of the most dynamic actors around (see his Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma), but the role of Henderson gives him virtually nothing to do apart from look slightly pained every time he tries to help out and gets insulted. Mort has neither discovered nor invented anything remotely compelling about this relationship, which makes her choice to skip past most of Simone’s life and career seem less creative than just plain absurd.

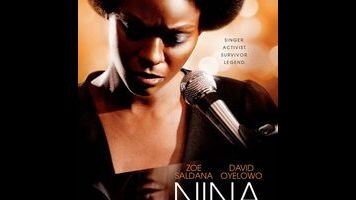

Ironically, given all of the fuss surrounding her casting, Saldana is easily the best thing in the movie. No, she doesn’t look anything like Simone—especially since Saldana is 37, whereas Simone was in her 60s at the time that most of Nina takes place. (Weirdly, no attempt whatsoever is made to age her, even though the film begins with a childhood prologue set in 1946, clearly establishing the timeline.) Nor does Saldana sound at all like Simone during the performance sequences, though she has a lovely singing voice of her own. But she does at least intermittently succeed in capturing Simone’s imperious manner, thereby providing this non-story with what little vitality it possesses. Alas, there’s not much she can do with Mort’s blunt dialogue; this is a movie that introduces Richard Pryor (Mike Epps), who once opened for Simone, by having him say something along the lines of, “Man, first I set myself on fire freebasing coke, and now this multiple sclerosis shit.” It’s always something, isn’t it, Richard? Except in Nina, where, somehow, despite the endless possibilities, it’s never anything.