No actor escapes unscathed in the abysmal ensemble Mother’s Day

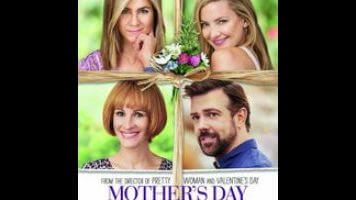

Garry Marshall is, at least nominally, an actor’s director. His early career in sitcoms made him a specialist in helping stars find a persona. He directed Julia Roberts to her most famous performance in Pretty Woman. He’s worked as a character actor himself. He’s also engendered enough comfort and loyalty to recruit all-star casts for three separate holiday-themed interconnected-ensemble comedies, of which Mother’s Day is the latest, following Valentine’s Day and New Year’s Eve. It’s grimly fascinating, then, to see how this actor-friendly filmmaker manages to direct so many recognizable stars to such terrible performances. Mother’s Day, in contention for Marshall’s worst holiday parade, becomes an unintentional meditation on the hollowness of stardom, as name actors ghost their way through imitations of their past triumphs.

Collectively, Jennifer Aniston, Julia Roberts, and Kate Hudson, the three biggest stars in Mother’s Day, represent decades and dozens of romantic comedies and domestic dramedies. Yet this movie never feels like the work of old pros, or young pros, or anyone of any age with much acting experience. Because the characters are played by movie stars, they do feel familiar, especially Sandy (Aniston), whose easygoing ex-husband (Timothy Olyphant) has remarried a younger woman who gets access to Sandy’s kids without putting in any of the hard work. Aniston’s self-pitying persona emerges in full force and is stripped of any meager comic potential. Her entire shtick consists of disdainfully repeating words as if they’re the keys to her unceasing misery, whether it’s the name of her would-be rival (“Tina!”), vexing young-person technology used by her would-be rival (“tweet!”), or the subject of a supposed joke (when she’s talking to a birthday party clown, she says “clown” over and over).

Aniston is bad here, but she’s not alone. Marshall allows everyone in the movie to either play to their worst instincts or avert their eyes while skipping through the wreckage. As a home-shopping celebrity hiding a secret, Roberts mugs unbearably for her show within the film, then goes stiff for her big emotional scenes later in the picture. Jason Sudeikis, playing a widower raising two daughters, looks narcotized not with grief but with indifference. Kate Hudson, as Aniston’s friend Jesse, comes off the best simply by not appearing in much of her storyline, wherein her bigoted parents (Margo Martindale and Robert Pine) learn that she’s married to an Indian man (Aasif Mandavi) and that her sister (Sarah Chalke) is married to a woman.

That faint sense of inclusiveness is one of the few things Mother’s Day has going for it. But then, most of the movie’s writing is so terrible that a lack of outright hate speech starts to feel like a major positive. Lots of bad movies use bad spoken exposition, but it takes a special kind of screenplay, one written by a klatch of Marshall hangers-on, to make it sound not just awkward but repetitive and almost confusingly descriptive, as if written for blind children. Some of the information-imparting gems include “I’m your sister and I live next door to you,” “I have abandonment issues,” “There’s a reason we moved here to Georgia” (the movie goes on to name-check its tax-credit location repeatedly, but never more specifically than saying Atlanta, Georgia), and “Mom loved karaoke” (which leads to a later moment where a character helpfully explains, “It’s a karaoke machine” twice in about two minutes).

At least these lines have the clear (if insulting) purpose of explaining every detail to the dummies in the audience. In other scenes, the actors seem to be talking around the situations at hand, like they didn’t have time to memorize the screenplay’s reams of exposition and just had to wing it. Maybe this accounts for the mismatched grammar in exchanges like this: “Who is giving this young lady away?” “I do.” As many grammatical mistakes as the movie makes, it’s possible even more were fixed, because it also seems to contain an unusual amount of ADR. Or does Marshall just not like showing his actors’ mouths moving? His cutting makes it hard to tell.

His cutting, along with his framing and timing, also makes it hard to tell even the simplest jokes. At one point, Olyphant engages in a bit of slapstick so mild that the gag is 20 percent soft, cushioned pratfall and 80 percent reaction shots (including one of a llama). Sometimes, Marshall and his writers’ room give up on the hard work of forging their own hacky gags and settle for references to other films from the Marshall dynasty, like a Pretty Woman “salad fork” non sequitur between Roberts and Marshall’s smug mascot Hector Elizondo, or a scene where Sudeikis must wanly refer to A League Of Their Own (directed by Marshall’s sister Penny) by announcing that “There’s no texting in soccer.”

It’s hard for a comedy to be so bad it’s funny, but Mother’s Day gets there more than once through a combination of sheer incompetence and desperate emotion; the only thing it’s worse at than setting up and delivering jokes is yanking on the heartstrings. The film starts out with an advantage over its predecessors in that it’s free to explore a variety of familial relationships, rather than single-mindedly fancying itself some kind of ultimate, all-encompassing romantic comedy. But in Marshall’s hands, this distinction doesn’t matter one bit. This whole world is one big romantic comedy, which in his hands means a sappy greeting card that isn’t particularly funny. The mother-child bonds don’t even register, because most of them are actually about the absence and/or symbolic value of a mother, not actual relationships.

All those actors must find some degree of well-paid comfort in this numbing stupidity, though by the end of Mother’s Day, it’s worth asking whether Marshall and his cronies constitute some kind of hostage-taking Hollywood mafia, forever calling in favors to get another vanity project running. Maybe it’s time for some of them to start planning exit strategies. Jennifer Garner, a Valentine’s Day veteran, has a cameo here as Sudeikis’ departed wife—a U.S. Marine, of course, because all three of Marshall’s holiday epics pay mawkish tribute to the troops. (Here, a shot of Garner’s gravestone is tastefully adorned with stirring military drumbeats.) In other words, the sweet release of her character’s death spares Garner the humiliation of appearing in more than one scene of Mother’s Day (though not the humiliation of sentimental onscreen karaoke). Roberts, Aniston, Hudson, Sudeikis, and everyone else should start plotting their characters’ gruesome demises before they get the call for Memorial Day.