No-budget African action studio Wakaliwood is ready to take over the mainstream

Isaac Godfrey Geoffrey Nabwana (Nabwana IGG) isn’t sure exactly how many movies he’s made. He thinks it must be at least 50, but many of them are lost now, some ruined by power outages that crashed his computer and others deleted on purpose to make room on his hard drive for more footage. “Sometimes I remember the titles, like, ‘Oh hey, I lost this movie,’” he tells The A.V. Club over Skype. “It’s a sad moment, like losing somebody. Like losing a baby.” But he does know how many times he’s been in a movie theater: exactly once, on Saturday, September 12, 2019, closing out the Midnight Madness program at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival. And he got a five-minute standing ovation that moved him to tears. Nabwana, who also goes by “Isaac,” is the visionary behind Ramon Film Productions, a.k.a. Wakaliwood, a compound of tin-roofed buildings that also serves as a DIY action-movie studio prolific enough to impress even a Bollywood producer.

The Wakaliwood story has been slowly trickling out into the wider world for a few years now, and has been featured in everything from Vice to The Economist. The basic outlines are these: Wakaliwood is located in Wakaliga, an impoverished area of Uganda’s capital city of Kampala where, until recently, internet access was expensive and spotty—a problem for Isaac, who, along with electricity issues, has had uploads spoiled by internet outages more times than he can count. (“My first internet [connection] was a land line, and it was so slow,” he tells The A.V. Club with a rueful shake of his head.) Isaac is a self-taught filmmaker who bought his first camera with money he made making bricks and who’s been obsessed with action movies and martial arts since he was a kid. “[It] was around 1986 when me and my brother Robert found a magazine from China that was showing demonstrations of martial-arts movements, and we started teaching ourselves from these magazines,” he says. And his films—which typically run about an hour long, take about a month to make, and cost around $200 U.S. dollars—reflect not only his desire to bring people together, but also his boundless ingenuity, enthusiasm, and persistence.

It’s a philosophy that can be summed up as, “We couldn’t get a helicopter, so we just made a helicopter”—which sounds like a figure of speech, but is entirely literal in this case, as the helicopter made of scrap metal sitting in Isaac’s yard can attest. This self-starting attitude was atypical—and, to an extent, still is—in a country still struggling to recover from the violence and ethnic cleansing of the Idi Amin regime. As Isaac explains:

No one was willing to make a movie in Uganda. I told my brother that one day I would make a movie and he said, “No, you need millions of dollars to make a movie.” But I don’t see where they’re putting the money. These guys are talking, and there’s a camera set up somewhere, and then someone punches like we do when we’re sparring… We used to do exactly the [choreography] we saw in the movies. So I told him, what I see in a movie is art. It’s not money. That was the major thing driving me towards my dream. Yes, money is needed somewhere—you need a camera, you need blood. But the major thing is art.

Nowadays, Wakaliwood has wifi, and the upstart studio has become a phenomenon in Uganda, if not an entirely respectable one. Isaac says his actors get recognized on the streets of Kampala, and while most of the time, no one knows who he is, his local TV appearances have raised his profile. “At first the media here never paid much attention to us. When they saw international media coming here, that’s when they started taking an interest,” Isaac says. Wakaliwood is not exactly popular among the Ugandan upper classes, who don’t like the idea of no-budget action movies with more gunplay than a John Woo epic representing the country abroad.

It’s a problem Wakaliwood’s official ambassador to the West, ex-film festival programmer Alan Ssali Hofmanis, is very familiar with. (Hofmanis sold everything he owned and moved to Uganda to serve as Isaac’s international sales rep/producer/marketing department/white-guy bit player in 2011. He plans to stay as long as Isaac, whose talent he calls “the real deal,” will have him.) Hofmanis says he’s started to see hardcore fans showing up at screenings dressed up like the characters and quoting along, but that production companies and government officials, both in Africa and the U.S., still don’t seem to know what to do with Wakaliwood. “It’s going to take time,” he says. “It’s never really happened before that someone from that part of the world, a culture that seems so far from Hollywood, becomes pop.”

And it is true that much of the African cinema that makes its way abroad is of the serious, “issue movie” drama variety, which is—well, which isn’t what Wakaliwood is about at all, even if the film that brought Isaac to Toronto, Crazy World, ends with a title card proclaiming, “Let us join children to fight child kidnapping!” Life in Uganda is very different from the U.S. or Canada: In one especially dramatic example, Isaac says Crazy World, an action-comedy about a kung-fu fighting gang of pint-size “commandos” who defend themselves against the criminals who plan to use them as human sacrifices, was made partially to discourage the kidnapping of his own children. But the power of a shared cultural language born out of Hollywood (and Hong Kong) exporting their movies to every corner of the world can’t be underestimated. Jet Li, Bruce Lee, and Chuck Norris (Isaac’s favorite) all get shout-outs in Crazy World, which opens with a hilarious anti-piracy ad where “Piracy Patrol” agents drag a villager off to downloading jail, chiding the man as he screams he did nothing wrong, “You watched Rambo without permission!”

But while Wakaliwood movies are without a doubt inspired by American and Chinese action movies, they also reinvent the form in a way that’s specific to their African roots. Films are generally watched at home or at impromptu “video halls” in Uganda, and at public screenings, a performer called a “VJ” or “Video Joker” will comment live on what’s happening on screen. This serves two purposes: One, it helps viewers who speak one of Uganda’s many dialects and indigenous languages understand what’s happening in an English-language movie. (The official language of Uganda is English, but Isaac estimates that about 60% of Ugandan villagers aren’t fluent.) And two, it makes the slow parts in between the fight scenes a lot more fun to watch. Wakaliwood continues this tradition, adding VJ tracks to all its movies that proclaim as the film starts, “Welcome to Wakaliwood! Home of the best of the best action movies!”

Isaac has his own personal VJ, Emmie, who accompanied him to TIFF to VJ Crazy World live—the first time he’s done such a performance outside of Uganda. Emmie’s main role is to serve as a hype man for the action that’s unfolding on screen, sometimes shouting simply, “Movie!” during an especially exciting fight. But as he’s honed his craft over dozens of films, Emmie’s style has evolved into something more akin to a comedian hired to do punch-up on a script. And his jokes are both very silly and very meta, in dialogue with the movie and the audience watching at home.

The VJ tracks are also full of in-jokes: In Isaac’s 2016 movie Bad Black, for example, a character breaks a window with a hammer, prompting a crack about “Ugandan keys.” That’s something that’s important to Wakaliwood, Hofmanis says, pointing out that Isaac always includes raw sewage in his films in one way or another as a signifier for Ugandan viewers of where these films are coming from. “If you live in the village, you know what [raw sewage] is, and you’re not afraid of it. It’s part of life. So I think these are visual signifiers that Isaac uses to separate his films from everything else being made in Uganda… [It’s] basically a fuck-you from Isaac. It’s a strong wording, but it’s definitely placing it, like, ‘This is who we are and where we’re from.’”

Isaac also shares Emmie’s propensity for breaking the fourth wall: Midway through Crazy World, the Piracy Patrol interrupts the movie to threaten to send TIFF Midnight Madness programmer Peter Kuplowsky to Somalia because he’s watching the movie for free. That’s typical of a Wakaliwood screening, many of which come with a personalized video introduction made especially for that audience. And, until TIFF 2019, those video introductions were necessary because Hofmanis is the one member of the Wakaliwood crew whose American passport has allowed him freedom of travel. Even after Isaac won the Audience Award at Fantastic Fest in 2016—a prize that usually comes with a festival pass for the following year—American officials refused to grant him a visa because he didn’t have enough money in the bank (about $35,000, by Hofmanis’ estimation) to “guarantee he wouldn’t stay” in the U.S., as Hofmanis puts it. (The fact that he has a family and a business back home was considered irrelevant.) Isaac and Emmie also reportedly faced extra scrutiny from skeptical border-patrol agents that delayed their arrival at TIFF, one of the most prestigious film festivals in the world, at which their film was an official selection.

Although a title card in Crazy World reads, “produced, written, directed, shot, and edited by Nabwana IGG,” Isaac’s Wakaliwood crew has continued to grow as the fledgling DIY studio enters its second decade. The whole family gets involved: Isaac’s wife helps out with directing, editing, writing, and makeup; his oldest daughter is a musician; his son helps edit; and another son co-stars as a kung-fu kid in Crazy World. Beyond Isaac’s immediate family, there are also his many apprentices, to whom he’s passed down hard-earned lessons in film production and editing. (There aren’t a lot of film jobs to go around in Uganda, but some of Isaac’s editing students have gone on to work in TV or on music videos.) And all of Wakaliga gets involved in shoots, with shopkeepers and various neighborhood characters playing themselves. Asked what he would do if he did get a multimillion-dollar budget for one of his movies, Isaac’s love of his community shines through:

I’d set up a film village. That way I would make more than a hundred movies. And with the studio I could teach, you know? There are so many young people here—something like 70% of Ugandans are youth—and we don’t have the ability to employ all of them. So I like the idea of a place where I can teach them, and I can employ them, and then they can start working, making more movies. That’s what I would do with that money.

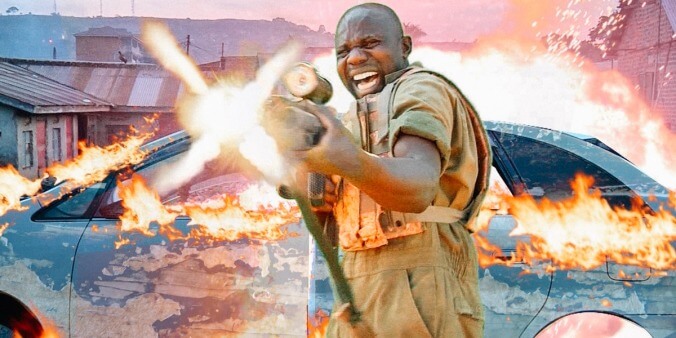

These locals have coalesced over the years into a stock company of characters one might call the Wakaliwood Cinematic Universe, made up of good guys (Commandos), bad guys (Mr. Big and his Tiger Mafia), and lone wolves like Bruce U, a recurring character in several Wakaliwood movies Emmie describes as “Uganda’s best kung fu cop and action star!” In action-comedy after action-comedy, these Wakaliwood superstars go on adventures in the brick buildings and garbage dumps of Wakaliga, throwing themselves off of roofs and staging kung-fu fights that Isaac films with shaky mobile camerawork and quick cuts reminiscent of a Michael Bay movie. Wakaliwood action movies frequently start and end with a gunfight, punctuated with CGI blood and explosions. But in between pretty much anything can happen, from black magic to an autobiographical vignette where a movie director buys one of his own films from a bootlegger on the street.

The pacing is wild and manic, and the films, for all their no-budget goofiness, are compulsively watchable thanks to Isaac and Emmie’s joint sense of irreverent humor. In Crazy World, a Reservoir Dogs-style shot of the Tiger Mafia gang walking toward the camera is ruined when one henchman keeps going as the rest of the crew stops and poses. His boss, a childlike man no more than 5 feet tall, gestures for him to bend over so he can slap him, and Emmie exclaims, “Ugandan Hulk!” Asked about comedy in his films, Isaac says, “there are certain things that are universal. Comedy is universal. When I make a movie that’s supposed to be violent, you also have to keep people laughing… I call them stress-free movies.”

And Hofmanis believes that the desire to put your problems aside and just have fun for an hour isn’t the only universal thing about Wakaliwood. Asked if he’s worried if audiences abroad are receiving the films in the spirit they’re intended, he reiterates that it’ll take time, and that when he started presenting these movies abroad in 2014, “it was definitely, ‘This is so bad it’s good. You’ve got to see it.’ And it was like that for about a year. But I distinctly remember the day when I saw someone else defending it—it was in some chat room—and they’re like, ‘No dude, you don’t get it. It’s not like that.’” He adds, “I always thought it was going to take five movies. After five movies there would be a reckoning, and people would get it. Now I think it may only take three. We’re in a transition period here… there’s going to be a gear shifting in the collective cinema head, like, ‘Holy crap.’”

And once that happens, Hofmanis says, there are Wakaliwood-style auteurs around the world just waiting to be discovered. “The technology to make films for nothing is 10 years ahead of the technology to distribute for nothing,” he says. “I think [Isaac’s 2010 film] Who Killed Captain Alex? and Wakaliwood are the first of something. It’s the first, maybe through a combination of luck and hard work, but it’s not alone.” Other Ugandan villages have started making genre films, he says, and cites a Ghanian company called Ninja Productions that makes action/sci-fi films that “have millions of views, but just for, like, 30 seconds [of the film].”

And it’s not just Africa that’s experiencing a homegrown genre-film renaissance: Northern India has its own no-budget filmmakers remaking American movies in their villages, as does Afghanistan, where real rocket launchers and grenades are easier to access than prop ones. If and when he is able to help bring the Afghan movies to the U.S., Hofmanis jokes, he’s going to call the tour “Talibanned.” “It’s always action, and it’s always horror,” he says. “And if you ask [the filmmakers], they’re like, ‘It’s fun. Action is fun.’” It’s also relatable across cultures; as Hofmanis points out, a love story set in Afghanistan would be totally different from a love story set in Russia or Uganda or the U.S., but “everyone understands revenge, man.” He adds, “So with Wakaliwood and with Isaac coming [to TIFF], I think it’s going to put kerosene on this whole thing. It’s going to light the bonfire of a movement that doesn’t have a name yet.”

A Blu-ray double feature of Who Killed Captain Alex? and Bad Black, both directed by Nabwana IGG, is out now through the American Genre Film Archive. The Wakaliwood Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube accounts are also well worth the follow, and you can support Wakaliwood’s filmmaking efforts by buying merch from its official store.