Now and then, a studio grossly misjudges a movie by opting not to screen it for critics. But most of the time, they are sadly right; the film sucks, the studio knows it, and the last thing they want is a second opinion to rip into their already modest box office projections. Such is the case with The House, a creaky and crappy comedy that stars Will Ferrell and Amy Poehler as a suburban couple who set up an illegal casino and become small-time, Scorsese-inspired mobsters to pay their daughter’s college tuition. Whatever satirical intent the script might have (and it clearly has some) immediately surrenders to the lackadaisical, incoherent direction of Andrew Jay Cohen, a screenwriter (Neighbors, Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising) making his feature directing debut. The pace is hectic, but the jokes just aren’t there.

Ferrell and Poehler’s characters, Scott and Kate Johansen, are clingy squares who’ve pinned all their hopes on their only child, Alex (Ryan Simpkins), and can’t bring themselves to tell her that they won’t be able to afford to send her to Bucknell University after her full-ride scholarship is canceled because of a municipal budget shortfall. (In a scene that could be funny in theory, the residents of their white-bread, upper-middle-class suburb are asked to vote on either paying for Alex’s promised full ride or building the biggest public pool in the tri-state area.) A brief, incongruous night out in Las Vegas inspires the Johansens’ gambling-addicted neighbor Frank (Jason Mantzoukas) to hatch a plan to put their savings together and turn his foreclosed, empty McMansion (his soon-to-be-ex-wife left with the furniture) into a lavish gambling den so that he can pay off the bank and they can save face with their daughter.

As it happens, the missing funds are the result of some embezzlement by the sleazy town councilman (Nick Kroll), and the same locals who voted to cancel Alex’s scholarship immediately show up to blow thousands at the roulette and blackjack tables set up in Frank’s vaulted living room and then slug out disputes about potlucks and missing leaf blowers in an improvised boxing ring, their lost bets piling up in a row of safes hidden behind a large Thomas Kinkade print. There is some version of this story that satirizes the selfishness and resentment of mortgaged America—one that makes use of Ferrell’s Chevy Chase-like every-WASP qualities and the pricklier side of Poehler’s screen persona—but this is definitely not it.

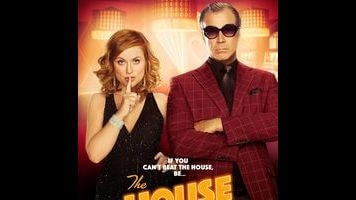

Like so many of today’s comedy journeymen, Cohen stages almost every scene by gluing characters into place and just having them talk at each other. But while he shows an almost admirable dedication to unexpected bursts of off-putting, grotesque violence (somehow, a man burning to death is the funniest thing in this film), Cohen blows through every other potentially subversive twist of the busy—yet still somehow very dull—plot. This includes almost everything that involves the running of the criminal enterprise (the casino just springs forth in a clumsy montage) and the Johansens’ transformation into crooks. The fact that Ferrell, dressed in single-color shirt-and-tie combos à la Robert De Niro in Casino, also parodies De Niro’s artful way of handling a cigarette is a nice but unwarranted touch; it’s a gag only in concept, as is so much in this eerily laugh-free movie. Its cast includes a lot of talented sketch players and comic improvisers (plus a perversely professional Jeremy Renner, who cameos as a local mob boss), but, as they say, everybody has their off days; if the torturously long reel of outtakes that plays before the end credits of The House is any indication, every day of filming was an off day.