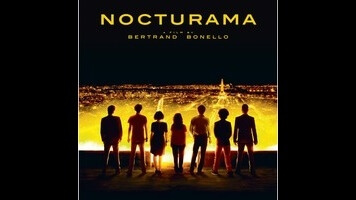

Nocturama is a mesmerizing, disturbing tour de force—and one of the best films of the year

A nocturama is the part of the zoo where they keep the small animals that only come out at night. The term is obscure, but evocative—so, an apt title for the audacious and disturbing new film by the French writer-director Bertrand Bonello (House Of Pleasures, Saint Laurent), the longer second part of which finds a group of mostly teenage terrorists hiding out in a windowless Paris department store after a spree of bombings and assassinations. We’ve seen them carry out these attacks over the movie’s mesmerizing first 50 minutes, sometimes replayed from multiple angles, though we are never exactly sure of their goal. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Bonello is a decadent movie poet of literal and emotional interiors with a uniquely cubist approach to both time and realism; his style is druggy and dreamlike because it’s so cornered, self-confined, self-refracting. In Nocturama, his radicalized night critters run free in the evacuated department store as he busts out one killer camera move after another to the best and most eclectic movie soundtrack in recent memory. If this is artistic self-indulgence, then please, please, let us have more.

On the twisting grand staircase, a young man does a sublime lip sync to the Shirley Bassey rendition of “My Way”—a scene that might qualify as the most punk needle drop of the year, if it weren’t for the use of Willow Smith’s “Whip My Hair” earlier in the film. Outside, the street is eerily empty and quiet. Though Bonello isn’t a marquee name, he has matured into a singular talent of modern film. His characters live within themselves; his editing and use of music and fantasy is really unlike anyone else’s. He’s an aesthete who puts a lot of stock in clothes, furniture, and cool music, which makes it all the more perversely perfect that he should make a movie that’s all ugly backstairs, track pants, and conspicuous consumer goods. The mise-en-scène is pointedly empty at first. It’s a lot of concrete, bare walls, vacant office spaces, and pedestrian tunnels, stretching a blank canvas around the characters that is later painted in the multi-level panoramas of clashing patterns, glitzy display cases, corporate logos, and sight gags of the department store. It’s stylish and heightened and it refuses to compromise.

The filming location is La Samaritaine, the shuttered Art Nouveau complex seen in the Leos Carax films Lovers On The Bridge and Holy Motors. But Nocturama—which is set over the course of about 12 hours with some flashbacks to earlier events—doesn’t get there right away. No, it begins in mysterious, elliptical, coordinated movements around the city, drawing parallels, puzzling together a terrorist plot as it paces its own timeframe, retracing itself minutes into the past to see what every character is doing at every step. We first glimpse Paris from a helicopter and then from a back of a Métro train as it escapes down a subway tunnel: the bird’s eye view and the secret below. We first get to know the characters as bodies in motion and don’t learn most of their names until well into its ample running time. Perhaps a lesser movie might take pains to show that the people behind it understand that terrorism is, in fact, bad. Of course, if this is something a viewer needs explained to them, then they have problems that no French art film, however awesome, is going to solve.

In the early going, the movie’s focus is monkish and hypnotic. Steadicams closely stalk the characters as they skulk down hallways, slip through service doors, text, change clothes, plant sticks of orange Semtex putty, execute people they may or may not know with point-blank gunshots. It should be noted here that Nocturama, which has taken some time to make it to American theaters, was filmed before the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, from a script that was written years earlier, before Saint Laurent—and anyway, it isn’t morally ambiguous. For all the varieties of filmic pleasure it mainlines and all the tried-and-true genre thrills it twists to its own ends, it draws the line at violence, which is always abrupt and sobering in the film. But that isn’t to say that Bonello isn’t above sadistically toying with viewer sympathies and anxieties or mounting a climax that is as formally ingenious as it is crushing. There’s something to be said for putting terror in the hands of a bunch of moody young people who don’t look like they would show up at the same party, let alone form an extremist cell. It filters out everything but the true common denominators: frustration, alienation, futility.

Any good film nerd can rattle off Nocturama’s likely inspirations: Alan Clarke’s experimental TV film Elephant; Jean-Luc Godard’s movies about hip young Maoists; cramped American genre classics like Dawn Of The Dead and Assault On Precinct 13, which echo through the consumer dream-space and hopeless barricade mentality of the department store and in the synthy burbling of Bonello’s electronic score. Perhaps there is some of J.G. Ballard’s postmodern fiction in there, too. But the film is a masterstroke of synthesis; whatever it borrows, it makes its own. It’s a dramatic principle: Bonello’s characters lose and discover themselves in art and hedonism and his angsty every-terrorists are no different. It’s the fireworks finale to the writer-director’s informal trilogy about the modern world, preceded by the opiated period piece House Of Pleasures and the anti-biopic Saint Laurent. All three films are very nocturnal, interiorized, abstracted, and sensual, and they all deal with inner spaces, dreams, and characters who are cut off from reality. Space is psychic in Bonello’s movies, and there’s a lot of it in Nocturama.

Cutting through streets or hustling up and down escalators in the tunnel-vision first section, the characters appear possessed by terror, as though under the mind control of some Dr. Mabuse-esque supervillain. Their targets are banks, office buildings, government officials, monuments, public space—the staples of terrorism, regardless of affiliation. But as they hole up in the store, they open themselves up and become lost in space. Yacine (Hamza Meziani), a busboy, wallows in luxury, changing clothes, guzzling expensive cognac, and racing a go-kart around the aisles; he’s the one who pretends to belt out “My Way.” Sabrina (Manal Issa), who might be Yacine’s sister, obsesses over the events of the day, which all seem like premonitions of bad things to come. Mika (Jamil McCraven), the youngest, only a kid, gets locked in the service stairs and later is visited by a ghost. The members of the terror group—the ones who’ve made it to the rendezvous, anyway—live out fantasy lives, playing dress-up; donning masks, wigs, and makeup; slipping wedding rings on each other’s fingers; filling claw-foot tubs with champagne buckets of hot tap water.

Music blasts from the stereo aisle and they get caught up in it. David (Finnegan Oldfield), who appears to be some kind of college student role-playing as a ’70s left-wing militant , roils with guilt and self-doubt. He sneaks a few times out into the street and invites a homeless couple to have dinner with the group. This subplot is probably the weakest aspect of Nocturama, but great films don’t have to be perfect. Instead of casting the movie into a moral void, its totally abstract treatment of terrorism cuts through the bullshit. It doesn’t matter if these characters make sense as a terror cell, it says, because they are credible as different kinds of terrorists. Nocturama embraces abstractions and contradictions and locates meaning in them: the terrorists’ need for attention and fear of being caught; the symbolism and meaninglessness of the plan; their status as sworn enemies of the status quo and creatures of the modern world; the contrast between the scale of the attack and the claustrophobia of the group’s blinkered point-of-view.

Wandering the city, David encounters a young woman about his age, and pretends not to know what’s been going on all day. Shrugging, she gives the closest the movie offers in the way of a motive: “It had to happen, right?” The truly subversive and transgressive thing about Bonello’s dark vision is that it acknowledges that this is all horrifying and even psychopathic, yet still recognizes the purely human foibles of its characters. And of course, there’s the inevitable question: If this is the nocturama, then what’s the zoo? As he returns to the department store, David passes a car engulfed in flames. We don’t know who set it on fire.