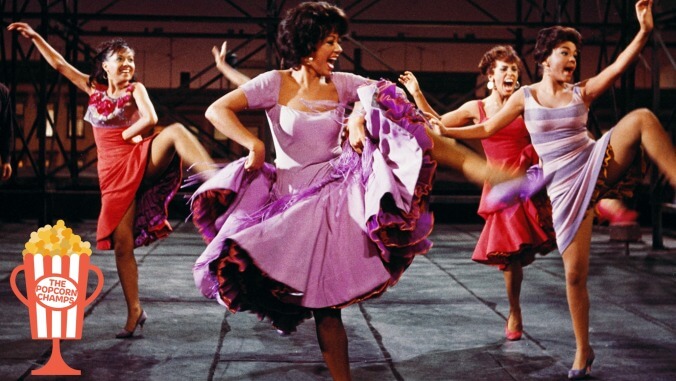

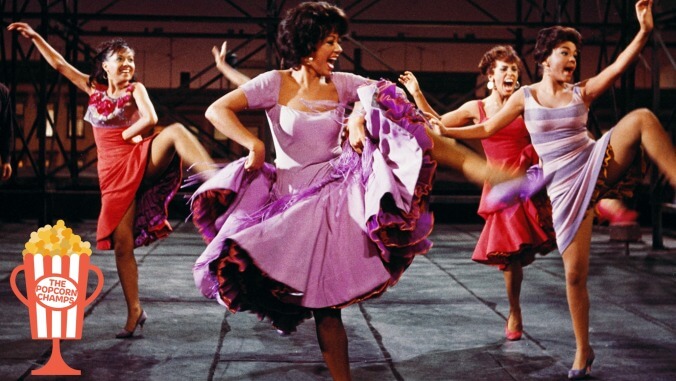

Not all of West Side Story has aged gracefully, but its spectacular dancing sure has

Image: Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

There’s a moment in West Side Story, the tragic and melodramatic musical that was 1961’s biggest box-office hit, where whirling bodies drift out of focus. It’s a simple transition between scenes, a way to get from a cluttered Upper West Side tenement apartment to a crowded dancehall. But it also speaks to what really works about West Side Story—the aspects of the movie that transcend historical eras, even as so much of it is hopelessly mired in its own time. In that moment, those bodies transform into shapes made out of light, into pure abstractions. They shows us, in a way, what’s thrilling about West Side Story: The power of bodies in motion, the way that watching them can play tricks on our brain. It’s what the movie gets right.

There is a lot that West Side Story does not get right. Consider this: One of the best things about West Side Story is the presence of Rita Moreno, who plays the tough but caring girlfriend of Bernardo, the leader of the Puerto Rican gang the Sharks. Moreno was a Puerto Rican woman who was playing a Puerto Rican woman, something that didn’t happen often in early-’60s Hollywood. And yet Rita Moreno had to wear brownface. All the white actors who played Puerto Ricans in West Side Story wore dark brown makeup, so Moreno had to wear dark brown makeup, too, so that she could match their skin tone. “It was like mud,” Moreno remembered, decades later. And when she tried to complain to the makeup artist, the makeup artist asked if she was racist.

Now, Moreno had been acting in Hollywood movies for more than a decade by the time she was in West Side Story, and she’d barely ever gotten anything bigger than a bit part. She won an Oscar for her work in West Side Story, and she went on to have a great career, though much of it has been onstage or on TV rather than in movies. Right now, Moreno is an 87-year-old EGOT winner, and she’ll return in the (possibly ill-advised) West Side Story remake that Steven Spielberg has in pre-production. She is a legend. But for her to be in this hugely popular and well-intentioned movie about why we shouldn’t let racism divide us, she had to be slathered in dark-brown makeup. That’s pretty fucked up!

West Side Story is an antiquated movie in all sorts of ways, not all of them problematic. Rewatching it recently, I had to spend the opening scene wrapping my mind around the idea that the movie’s teenage gang toughs—the ones who snap their fingers in unison, and who leap into florid and balletic dance moves even when they’re supposed to be fighting—don’t look even remotely intimidating. But they probably didn’t look intimidating in 1961, either. Instead, the movie presents a heightened Broadway reality, a world where colors pop right out and where characters will break into elaborate singing routines in even the most tense situations. Authenticity was never the point. That probably goes double for the endearingly silly hepcat dialect, everyone calling everyone else “daddy-o.” Those gang kids aren’t there to look hard. They’re there to dance.

The Broadway version of West Side Story, with music from Leonard Bernstein and lyrics from a 25-year-old Stephen Sondheim, opened four years before the movie, and it was an instant sensation. The idea of attempting to tackle social issues via big-scale musical was still pretty novel, and West Side Story was a hugely elaborate show, with more dancing than anyone had ever seen on Broadway. For the movie version, United Artists hired the director Robert Wise, who had edited Citizen Kane and who had helmed a bunch of smart, well-made movies that fit into a number of different genres. But Wise didn’t direct it himself. Instead, he co-directed with Jerome Robbins, the director of the original Broadway play. Wise didn’t have any experience with musicals, and Robbins didn’t have any experience with movies. The idea was that Robbins would direct the musical numbers, while Wise would direct everything else.

It didn’t quite work out that way. Robbins put his cast through hell, shooting tons of takes, to the point where dancers were working through injuries. All those takes cost money, and Robbins got fired midway through shooting. For the rest of the shoot, his assistants took over his duties, though all the choreography was still his. Robbins still got co-directing credit for the movie, and he still won the Best Director Oscar with Wise. (West Side Story won 10 different Oscars that year, just one shy of the record set by Ben-Hur two years earlier.)

Robbins got results. The dance sequences in West Side Story are just stunning—all these bodies flying around in every direction, defying gravity, landing with absolute precision in their right place. The whole movie looks artificial, but much of it was shot on location in New York, which means those dancers were landing on cement. Even when they’re fighting, they’re graceful and expressive and acrobatic. The rumble scenes remind me a bit of Hong Kong martial-arts movies—dreamlike battles with their own internal logic.

When West Side Story wants to communicate things, like the characters of Tony and Maria falling in love at first sight, it does it without words. In that instant, Wise and Robbins tell us what they need to tell us with focus tricks and spotlights—stage techniques and film techniques, working together. And it doesn’t hurt that the songs are all bangers: Big and heavily-orchestrated numbers like “Jet Song” and “Maria” and “Tonight” and “I Feel Pretty,” all still standards decades later. The West Side Story soundtrack was America’s biggest-selling album of the year in both 1962 and 1963, which should tell you something.

Musicals, of course, had been big business long before West Side Story. They’d been big business ever since movies had sound. For most of their history, musicals had been about lightness and froth, about the pure joy in seeing what Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers and Gene Kelly could do with their bodies. But they’d also entered into an era when they tried to tell serious stories. The Rodgers & Hammerstein adaptation South Pacific, the highest-grossing movie of 1958, had told a story about love and war and racism. Otto Preminger’s Porgy And Bess, from 1959, was a message movie with a predominantly black cast. But West Side Story went bigger with its ideas, using the power of myth to tell a contemporary story.

West Side Story is, of course, a Shakespearean adaptation, a contemporary retelling of Romeo And Juliet. (It’s an inexact retelling, with a less tragic ending and a radically reshaped arc.) But Shakespeare didn’t invent the idea of doomed teenage lovers. He was adapting the medieval legend of Tristan and Iseult, and maybe that had come from something older, too. It’s one of those stories that’s woven into our DNA: the depth and purity of young infatuation, set against the heartless societal forces that are endlessly conspiring to tear kids apart and to end their happiness.

West Side Story used that framework to talk about racism, which was a problem then and which remains a problem now. The Jets, the white kids in the neighborhood, don’t like the idea of Puerto Ricans coming into their space. They react with pure, unblinkered racism: “Every Puerto Rican’s a lousy chicken!” They worry that the Puerto Rican gang is nothing like the others that they’ve encountered, that the newcomers will fight more savagely. The Sharks, meanwhile, have come to New York and realized that this promised land will always be hostile to anyone who isn’t white.

We’re supposed to believe that all of them are teenagers, and there are precious few adults in the story: a kindly shopkeeper, a clueless social worker, a few embittered cops. The most prominent cop hates all of them. He taunts the Puerto Ricans: “It’s a free country, and I ain’t got the right. But I got a badge. What do you got?” But when the white kids won’t help him out, he explodes at them, too, calling them and their families “tinhorn immigrant scum.” (The Jets, we learn, were the invaders not too long ago.) Everyone is struggling for land and for pride, and nobody has any ideas on how they could all just share the city peacefully. And the movie never makes this seem like their fault. Instead, they’re all victims of larger societal forces at work. They’re desperate to hold onto what little they have, even though that fight might doom all of them. When things turn tragic, that kindly shopkeeper tells a Jet, “You make this world lousy.” He responds, “We didn’t make it, Doc.” They’re both right.

Against this unforgiving backdrop, Tony, a former Jet who’s left the gang life behind, falls in love with Maria, the younger sister of the Sharks’ leader. They’re happy for a few brief, shining moments before it all turns to shit. The movie ends with Tony dead in the street, and it’s a mythic conclusion, the only one that could’ve ever happened. The whole story plays out with a grim inevitability.

But for West Side Story to work as something other than beautiful spectacle, we have to buy the idea that Tony and Maria really are in love. That’s a problem. Natalie Wood, who plays Maria, had already been nominated for an Oscar for Rebel Without A Cause, and earlier in 1961, she’d been grandly sympathetic in Elia Kazan’s Splendor In The Grass, the movie that won her the West Side Story role. She’s the closest thing to a movie star in a cast that’s full of unknowns, many of them from the stage. Wood projects warmth and sweetness. But her character has no real depth, and she often seems to make decisions because of plot requirements rather than human feelings. I can’t get past, for instance, how she takes mere seconds to forgive Tony, a man she’s known for a couple of days, for straight-up murdering her brother. And it doesn’t help that Wood, who was Russian-American, does the entire role in an exaggerated and ridiculous Puerto Rican accent. Wood didn’t do her own singing in the movie, either, and neither did most of the principal cast.

(A morbid aside: Wood drowned in 1981, when she was 43. She’s the only major member of the young West Side Story cast who isn’t still alive. Wood’s death, initially ruled an accident, was always suspicious, and it’s remained a subject of some fascination. Last year, her husband—the actor Robert Wagner, who was in the movie that’ll be the subject of this column’s next edition—was named a person of interest in Wood’s death.)

Wood reportedly didn’t get along with Richard Beymer, the actor who played Tony. And the two really don’t have much chemistry in the movie. Beymer just isn’t up to the task of carrying the movie. He’s a blandly appealing ’50s-style leading man, and he can’t summon the passion or the intensity necessary for the role. Wise originally wanted Elvis Presley to play Tony, and even though Elvis was never anyone’s idea of a great actor, he was a world-historically charismatic and magnetic figure. The movie would’ve been immeasurably better with him in the lead. (Col. Tom Parker, Elvis’ manager and one of the great villains in pop-culture history, shot down that idea.)

A mind-boggling array of future stars were also up for the role: Warren Beatty, Robert Redford, Burt Reynolds. Later on, Beymer admitted that he hadn’t really known what he was doing, and he remade himself as a character actor. Decades later, Beymer and Russ Tamblyn, who plays Jets leader Riff, would turn up in Twin Peaks. Beymer was Ben Horne, while Tamblyn was Dr. Lawrence Jacoby. Presumably, David Lynch loves West Side Story.

So the love story at the movie’s heart is a big blank. And since it’s a product of 1961, the movie’s anti-racism message is deeply clumsy, as broad and hamhanded as anything that Hollywood has cranked out since. It’s not just the accents and the brownface (which were everywhere in early-’60s movies, even in something as beloved as 1962’s Lawrence Of Arabia). It’s little things like Anita saying that she hopes Puerto Rico sinks beneath the ocean—something that I can’t imagine any Puerto Rican New Yorker saying, even in jest. Stuff like that has not aged well. And there are other time-capsule moments that are just fascinating: a threat of gang rape implied through a dance sequence, a tough young woman who absolutely glows with pride when a gang leader calls her “buddy boy.” Moments like those would be a bigger deal if they happened in movies today. Maybe it’s better that they just fly past, unexamined, letting us puzzle them out as we will.

But nobody rewatches West Side Story for the political message. Instead, the movie is still worth remembering today for its overwhelming physical power—for the way those bodies blur into light.

The contender: I don’t expect to write about a whole lot of foreign-language art-house classics in this column, but Federico Fellini’s lush and episodic La Dolce Vita was the #6 highest-grossing movie in America that year. The movie tells a few loosely interconnected stories about a suave and permanently horny gossip columnist who seems aspirationally glamorous at the beginning and tragically pathetic at the end.

It’s probably safe to assume that La Dolce Vita owed a ton of its U.S. success to prurient interest. Because of the Motion Picture Production Code, American movies could only barely imply sex, while Fellini could show Marcello Mastroianni hopelessly lusting after the Swedish pinup Anita Ekberg. But La Dolce Vita is also a hell of an achievement. You could take practically any frame of Fellini’s crisp, shadowy black-and-white imagery and hang it on a museum wall. And in its three-hour expanse, La Dolce Vita is just as much a spectacle as Hollywood epics like The Guns Of Navarone or El Cid, to name two other big 1961 hits. For that matter, La Dolce Vita is as much a spectacle as West Side Story.

Next time: John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Richard Burton, Robert Mitchum, and a whole lot of other famous people show their faces in the vast World War II epic The Longest Day.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.