It is said that the grand metaphor to describe the United States is a melting pot, where cultures from all over the world that have gathered in a shared space form a gumbo where their flavors merge, the whole supplanting the constituent parts. In Canada we habitually—perhaps with more smugness than the stereotypical politeness usually ascribed—refer to our nation as a “mosaic,” for a mosaic is made out of obviously disparate elements, each individual piece identifiable on its own. In this context our hyphenated backgrounds (Italian-Canadian, French-Canadian, Pakistani-Canadian) are worn proudly, the differences identified and celebrated. The idea is that our national connection as Canadians is one of cooperation and understanding, keeping the particularities in place while still finding a way to collectively identify.

While this dreamy, mostly self-congratulatory metaphor falls apart after even cursory examination, it does speak to a way we as a country habitually contrast ourselves with our neighbours (with a “u”) to the south, and how our personal pasts consistently inform how we see ourselves within our communities. It’s in this context that an American draft-dodger who abandons his homeland to become Canadian would be a very enticing thing for our cultural institutions, an outsider embraced as an insider, his desertion to be lauded but never forgotten. It’s in this broader context of the mosaic, and the fetishization of former Americans who now see themselves at least outwardly as Canucks, that I see the best parts of Paul Schrader’s fragmented Oh, Canada.

Decoupled from its mélange of aspect ratios, timelines and narrative inconsistencies, the latest from the scribe of Taxi Driver and The Last Temptation of Christ, and director of magnificent films from Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters to First Reformed, returns with a relatively banal tale of a cancer-ridden man at the end of his life, setting the record straight and attempting to recontextualize his past fabulations.

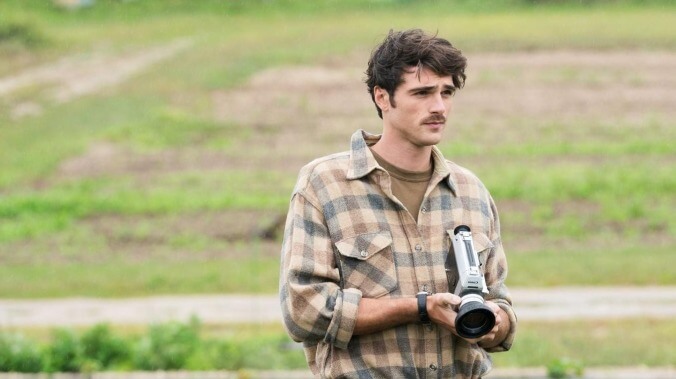

Based on the novel Foregone by the late Russell Banks (to whom Oh, Canada is dedicated), the story revolves around Leonard Fife, played over multiple timelines by both Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi. Uma Thurman plays Emma, Fife’s former student, now wife and collaborator, and the ostensive recipient of Fife’s cinematic confessional that rewrites the established history that helped bring him fame. Fife is described as the inventor of a type of subjectivist way of shooting documentary, with Schrader’s script wisely points to the shtick being borrowed from Errol Morris’ Interrotron.

Two other former students and classmates of Emma’s, Diana (Victoria Hill) and Malcolm (Michael Imperioli in imperious eyewear), have been tasked with capturing the final words of their former teacher for a television program. Along with their assistant and a patient nurse (in the novel she was Haitian-Canadian, which added to Banks’ regular racial critiques, but here such subtleties are avoided), they are all gathered to hear the final testament of this person we have been told, but not exactly shown, is a great man.

Fife’s progressive documentaries are indeed the stuff of National Film Board of Canada dreams: There’s an anti-seal clubbing tale, a courtroom drama involving a pedophile priest, and Fife’s first breakthrough, footage of crop dusters spraying chemicals over New Brunswick fields, inadvertently capturing the testing of the Agent Orange compound that would be used to deforest the jungles of Southeast Asia and wreak havoc for generations on the health of both those on the ground and those doing the spraying.

These films are presented with Spinal Tap-like verisimilitude, in contrast to many of the other aspects of Canadiana that feel weirdly false in this New York-shot setting. Fife’s Canada in this telling is indeed more metaphor than actuality, the irony of an anthem referring to his “home on native land” being a place he was not native to. The decision to stay in place or to go elsewhere is central to his youthful choices, with the overt crossroads made visually manifest by a sign that shows the state of Massachusetts to the left, and Canada (not Ontario, not Quebec, but a country—an idea) to the right.

Thus as settled as Fife is, he’s seemingly never escaped this liminality, shaped by a past he tried to invent, tortured by a present that’s literally killing him. His recollections are fragmented and often contradictory, and it’s here that Schrader’s style frustrates more than it succeeds. The idea is to put unreliable narration in visual form, but the promises of grander revelations are undercut by some of the frankly trivial, even stereotypical ways that is accomplished.

This, in turns, makes this grand CBC production feel even more false: There’s the incompetent if not neutered director, his supposedly superior collaborator rendered practically mute, his young assistant (and, based on Fife’s intimation, latest lover) obviously acting in a way that would have her fired off set, and his wife whose pleas to stop the project over and over again are, for reasons that are clearly narratively driven rather than believable in context, consistently ignored.

It’s churlish to point out, of course, but I couldn’t help but spend the latter half of the film wondering what exactly happened to those sandwiches that Emma went off to make, one of the more dramatic moments where her character finally acts with a bit of authority only to be undercut soon after, the food as forgotten as the final words of this man we’re told over and over again is going to reveal some grand truths.

And what are Fife’s truths that are finally revealed? Is there some shocking secret that truly does transform all that came before? My country has recently seen many artists and filmmakers outed of late for falsifying their pasts, not in terms of the supposed glory of being a draft dodger, but for passing themselves off as members of Indigenous communities, and thus speaking as authority for these long under-represented peoples. The baggage from that kind of lie being uncovered has been traumatizing, and speaks to much deeper pains within our community—a true scandal where the suffering of others is exploited by people enwrapping themselves in someone else’s history for the benefit of their personal and professional reputations.

Despite the relatively toothless confession and his mostly morose and argumentative demeanor, Gere’s portrayal of the ailing Fife is an engaging and welcome reunion with his American Gigolo director. Yet, there’s little to connect the more spry, at times fey, take on the role that Elordi is providing with the more stentorian one from Gere, making the portrait of the man even more sketchy than intended. Obviously, these are the differences between youth and age, but rather than facets of the same man, it felt like each performance was in its own unique film. The other characters are given little to do, as they are seen reflected entirely through Fife’s eyes, including one of the more meager handjob scenes in cinematic history that feels less tawdry than simply boring.

There are some gloriously camp lines (“We can’t cancel, we have a contract with the CBC!” is but one), but there’s one line that’s foundational to what’s going on in Oh, Canada. Fife proudly points out that he has a Genie and a Gemini, awards for both film and television under the previous organizations in Canada that gave out such trophies. In fact, they’re among the first things we see in Fife’s office, the set decoration showing off the triumphs of his decision to leave for Canada. Malcolm witheringly responds, “But I have an Oscar.” American success is the true marker that Canadians value.

As a Hendrix-like version of the anthem that gives the film its title fades into a twee, gentle acoustic rendition, tied to the Rosebud-like final gasp of a dying man, the declaration of what Canada means to Fife remains mostly oblique. This is clearly Schrader’s way of celebrating not only the novel but the writer himself (1997’s Affliction was also based on a Banks book), who also succumbed to the ravages of cancer. Just as cancer corrupts normal cells, Fife’s remembrances are themselves contradictory half-truths. Yet despite attempts to elevate the source material, Schrader’s telling falls flat, floundering in its attempts to translate literary looseness into a coherent, or even engaging, work of cinema. Oh, Canada feels less a deep rumination at the last moments of an artist’s life, and more the confused ramblings of an irascible, self-important character surrounded by sycophants unable to stand up to his unreasonable demands.

(This review originally ran on May 21, 2024 alongside the film’s Cannes premiere.)

Director: Paul Schrader

Writer: Paul Schrader

Starring: Richard Gere, Uma Thurman, Jacob Elordi, Kristine Froseth, Michael Imperioli, Caroline Dhavernas

Release Date: December 6, 2024