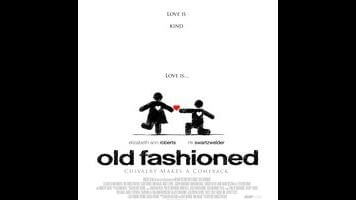

Swartzwelder stars as Clay Walsh, the owner of an antiques store in an Ohio college town, whose whispery voice, blond highlights, shaggy haircut, and assortment of XL sweatshirts, frayed baggy jeans, and Converse high tops suggests either a middle-aged man disguised as a teenager from the early 2000s or an afterschool-special sexual predator. This is a nice way of saying that Clay is innately creepy, which makes Old Fashioned seem creepy, because, unlike the doubting protagonists common to so-called “faith-based entertainment,” Clay is the absolute moral center of Old Fashioned’s universe. Sure, Clay struggles, but what he struggles with is—bless his heart—being loved so much for who he is, which keeps him from settling down with a new-in-town dream girl (Elizabeth Ann Roberts) named Amber Hewson. (What’s a youth-pastor type without a little U2 fandom?)

It must be pretty neat to make a movie that mostly consists of people telling you how chivalrous and morally right you are and how much everybody loves you, but that’s no excuse for making it this boring. Old Fashioned dawdles along from scene to scene, as Clay and Amber go on dates in a variety of engagement-photo-ready settings, drive around in Clay’s old Ford pickup, and interact with assorted largely extraneous characters. Admittedly, the movie’s pokey pacing and heavy-handed moralizing occasionally produce moments of inadvertent comedy, like the sequence where Clay expresses his frustration by angrily playing basketball, or just about any scene related to his past as a Girls Gone Wild-style amateur pornographer.

Despite having all the hallmarks of an over-stuffed, under-directed, one-man-band project—filled with the sort of mouthpiece speeches and go-nowhere subplots that make movies like The Room compelling—Old Fashioned lacks the type of personality that would turn its awkwardness into an endearing quirk. Like so many movies made for the increasingly lucrative Evangelical market—and unlike the scrappy, oddball Evangelical productions of yesteryear—Old Fashioned only aims to look and sound as impersonally professional as possible, which in this case means doubling down on burnished warm tones and setting every scene to soundalike rock and folk-pop. The lifeless result feels makes Clay and Amber’s chastity seem like a tedious slog toward a foregone conclusion.