Getting hit by a car will ruin your day in any country, but it may be considerably more dangerous in China. Last year, an article on Slate asserted that accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists there frequently prove fatal—not because the initial impact kills the victim, but because the motorist deliberately runs over the person again, sometimes more than once. The reason, the writer claims, is simple and practical, albeit horrific: Chinese law requires only a single payment to the family in the case of wrongful death, whereas injuring someone severely could mean paying their medical bills for many years to come. It’s just plain cheaper to kill, so some drivers make sure they get the job done.

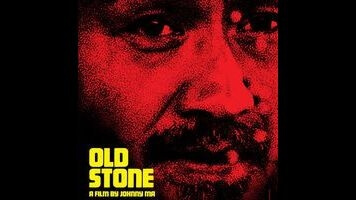

Snopes.com judges this phenomenon to be “unproven,” though some Chinese citizens clearly believe it, and Old Stone, the feature debut of director Johnny Ma, tries to build a narrative around it, with limited success. Because opening with an accident that becomes murder would leave the film with nowhere to go, Ma instead explores the predicament of someone who does the right thing, demonstrating what a mess personal integrity makes of the driver’s life. Middle-aged cab driver Lao Shi (Chen Gang)—the name apparently translates as Old Stone and is also a pun on “honest”—hits a young man on a motorcycle, then rushes him to the hospital (ignoring warnings from bystanders), where he gets roped into paying for the surgery. Expecting to be reimbursed by the family, he instead finds himself held responsible for months’ worth of hospital bills. It becomes such a problem that his disgusted wife (Nai An) withdraws all the money from their joint bank account, to prevent him from spending it on his victim.

That’s a fairly passive situation, and Ma seems to recognize that watching a poor schlub pay a comatose patient’s bills isn’t the stuff of high drama. Unfortunately, his efforts to give Lao Shi something active to do only serve to undermine the movie’s critique of Chinese compensation law. As it turns out, the accident wasn’t even Lao Shi’s fault—he hit the motorcyclist because a passenger, who was drunk, grabbed his arm. Conveniently, this passenger left his cellphone in the cab; instead of turning it over to the police and letting them question the guy, however, Lao Shi tracks him down himself and attempts to persuade him to make a self-incriminating statement. When that plan predictably fails, Old Stone gets downright absurd. It’s one thing to deliberately run over the person you hit just 30 seconds ago. It’s quite another to… well, not to give anything away, but let’s just say that Lao Shi decides that “get the job done” has no expiration date.

It’s too bad that the movie shifts from having too little juice to having too much, because there are hints of a more compelling middle ground. Lao Shi’s interactions with the police are fascinating—casual, nonmonetary bribes appear to be commonplace, to the point where the cops seem annoyed by constantly being handed cigarettes and watermelons. And Chen, though he has almost no prior career as an actor (one previous film appearance in 2008), registers empathetic befuddlement at the cost-benefit calculation everyone expects him to have made on the fly at the scene of an accident. That can only carry the film for so long, though. By the end, an examination of literal overkill winds up demonstrating the figurative kind.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.