The younger Kelly accounts for an all-too-rare moment of humanity within a genre-bending project that’s nominally about humanity’s present and future. Based on the book How We’ll Live On Mars by Stephen Petranek, the miniseries takes a dual approach to answering the book’s theoretical. In documentary footage, Petranek, Elon Musk, Ann Druyan, and others detail the preparations being made for an eventual one-way trip to Mars. Those preparations are then borne out in scripted scenes set in 2033, where an international band of colonists embarks on the seven-month journey to our nearest planetary neighbor.

But one half of the equation is always diminishing the other: Charlotte and Scott Kelly exhibit the type of relationship that can’t be ginned up for the fictional astronauts. Likewise, special-effects-laden, Nick Cave-and-Warren Ellis-scored scenes of space travel contain levels of drama and action that can only be implied in a Neil DeGrasse Tyson talking head. Sometimes, Mars splits the difference, like when it cuts between the failed landing of a Falcon 9 rocket and the dejected SpaceX engineers watching a simulcast of the fiery wreck.

More often than not, Mars makes the case that it should’ve been one thing or the other, and it probably shouldn’t have been the voyages of the starship Daedalus. While the documentary portion of Mars is brimming with personality, intrepid commander Ben Sawyer (Ben Cotton) and team feel like mere puppets of the predictions made by mad-scientist types (Musk, Mars Society President Robert Zubrin) and seasoned science communicators (Druyan, DeGrasse Tyson). They’re given their own interview segments to flesh out backstories and biographies, but the overriding sense is that the fake astronauts can’t become fully fledged characters when they’re jockeying for airtime with their real-world co-stars. That hurts Mars in matters of life and death—nobody wants to see a fellow human hurt (or worse) in this type of scenario, but with little reason to connect to these characters, any casualties incurred along the way feel meaningless. Or, like the “Buckminster Fuller designs an Apple Store” look of the series’ Mission Control, those moments feel like retreads of The Martian. (To be fair, Martian author Andy Weir is one of the miniseries’ interview subjects.)

Mars’ primary mode of distinguishing itself from similarly themed cinematic efforts is the scientific backing it puts on the screen. The Daedalus’ mission remains in the realm of science fiction, but the series derives a great deal of excitement from showcasing the people working to make it a reality. In the first episode, this comes across a bit too much like an advertisement for SpaceX, but the Kelly-focused passages of episode two offer a course correction. There’s a clever sequencing at play in the opening chapters of Mars: The first episode is about the equipment we’ll need to get to Mars; the second episode is about equipping ourselves for the ride.

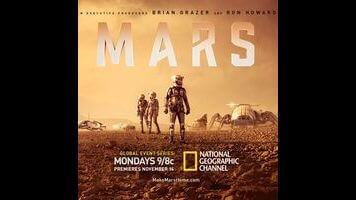

But Mars itself is a ride that’s only worth taking part of the time. It might be too scientific to achieve its ambitious aims, any feelings evoked on either side of the format divide needing to square with a rational, analytical case for going to Mars. And unlike previous, fictionalized space-exploration tales told by executive producers Ron Howard and Brian Grazer—Apollo 13, the HBO miniseries From The Earth To The Moon—Mars isn’t shedding light on the lives of people we only know from the news. (It’s no wonder the Kelly family steals the show in episode two.) As the miniseries tells it, the tools necessary for settling Mars will need to be multipurpose: rocket boosters that can be deployed for multiple launches, interchangeable circuitry for mid-mission emergencies. Unfortunately, Mars itself isn’t as versatile.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.