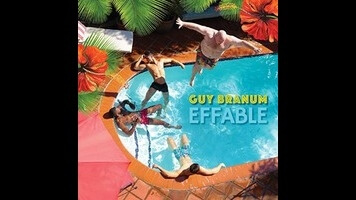

On Effable, Guy Branum imbues observational humor with personal pain

In a recent New York Times editorial addressing the outrage (and counter-outrage) over fellow comic and Daily Show heir apparent Trevor Noah’s unearthed Twitter jokes, Guy Branum struck a welcome note of equanimity, expressing his solidarity with Noah on his very public spanking over some questionable material. While never bestowing a blanket blessing to Noah, Branum (best known from his stints as writer/performer on Chelsea Lately and Totally Biased) acknowledges both how difficult the process of writing comedy is, and how the ubiquity and indelibility of social media turns the necessarily messy and disaster-fraught creative process into a permanent record. In his first album, Effable, Branum engages a Los Angeles comedy club audience in a lively, challenging discussion of their shared experience of being flawed, hypocritical people. As Branum puts it in the midst of some stellar late-set crowd work with an insufficiently honest audience member, “Nobody here is a great person. Let’s Truth and Reconciliation this shit.”

Branum is, as he puts it, “an angry, shouty, political gay guy,” but his set resists even the labels he continually puts on himself. He starts out with a number of zingers about himself and his sexuality (“In college they called me The Futon—because I was so good at making sex awkward and uncomfortable”). Then Branum quickly shifts direction, greeting the crowd’s laughter at his funny—if hammy—introductory material with a knowing, “That was nice, straightforward, one-liner jokes, you guys… I gave you jokes to greet you.” It’s not that the opening material’s not funny—it’s that Branum has bigger fish to fry.

Both the political and personal material that follows sees Branum playing the role of the exasperated truth-teller, a stance that his often-theatrical delivery should make tedious. Instead, Branum’s comic voice becomes a constant undercurrent in the material that follows, existing parallel with his trenchant insights into more traditional comic material (pets, New York vs. L.A., reality TV). As Branum puts it in a bit defending his use of internet apps for dating: “I am a unique, boutique product—like a left-handed oyster-shucking glove. Not everybody needs me, but those who do will really appreciate that they found me.”

In his observational material, Branum achieves the difficult goal of finding new angles on tired topics, his unique perspective as multiple-level outsider imbuing jokes with a manic—yet controlled—sensibility. Nothing’s less promising than railing against people who post pictures of their apartment-bound pets on Facebook, but Branum’s take draws on both his duality as a farm-raised fan of “real animals with genitals and a job” and a self-created cultural entity:

Your dog’s not staring out the window because she’s stupid. She’s staring out the window because she’s a housewife in 1963 with a journalism degree from Wellesley and two crying kids in the next room, wondering where it all went wrong. She’s the Betty Friedan of the animal kingdom.

This combination of observational comedy and biography is never more potent than his takedown of Brooklyn hipster culture (perhaps an even less-auspicious, more-threadbare conceit). Branum finds the faux-workingman posing of the entitled offensive less for its trendiness than for how it hearkens back to something from which he worked very hard to escape. Making his case against the “mixed-media artist” in work boots who can “afford rich people beer but drink[s] poor people beer,” Branum’s ire is directed at those whose affectations are born of a privilege untouched by what those affectations represent. This infusion of pained, heartfelt biography infuses even Branum’s seemingly impersonal material with surprising comic immediacy.

When brought to bear on his audience, Branum’s intensity ramps up even further, especially when his subjects are too timid to provide honest setups for his jokes. Throughout, Branum targets people in the audience for participation, his constant refrain—“a pretty name for a pretty face”—coming off as challenging as it is flirty. When attempting to set up a bit about the country’s changing stance of gay culture, he can’t get two straight guys to admit that they have ever used a stereotypical “gay guy” voice or called someone a cocksucker. Branum’s resulting tantrum is hilariously controlled, aggressively teasing out the truth that, as he puts it, “You’re allowed to be a little bit of a bad person.” As he expressed in his Trevor Noah piece, being human involves making a lot of choices that look really bad in retrospect. In getting his heterosexual audience member to finally admit to having that mocking gay-guy impression in his pocket, Branum makes the point that it’s a good thing that what used to be commonplace is now, culturally, not: “Now when you do that selfsame impression of the gay guy, you are one of the evil people in The Help who doesn’t think that Viola Davis should be able to poop on the inside like a normal person.”

Throughout Effable, Branum’s forceful, authoritative comic persona carries within it a core of vulnerability, even loneliness. It’s never maudlin or over-emphasized, but the ever-present knowledge that Branum’s polished and impressive stage presence comes at the cost of a lot of personal unhappiness and pain lends his set a lot of weight. In a concluding bit about his admitted bad taste in pop songs, Branum drops a biographical detail by way of explaining his love for the likes of Iggy Azalea and Katy Perry over The Decemberists that lands like an unexpected gut punch. Effable shows Branum scoring consistent comic points through personal pain.