On Narcos, an old enemy matches Pablo’s darkness

The world view expressed in “Cambalache,” the song that gave last episode its name, is hard to escape the longer Narcos goes on. As viewers—probably simply as people—we search for right and wrong, good and evil. It’s easier to process that way. In “Our Man In Madrid,” Pablo Escobar has a 10-year-old boy brought to him. The boy, David, is the survivor of a run-in with newly returned Search Bloc commander Carrillo who, recalled from exile in Spain by President Gaviria, has decided even more drastic measures are needed. So he rounds up David and a handful of Pablo’s other child spies in an alley and shoots one in the head, handing the terrified David a bullet as a message to Pablo.

If there’s a sure way to humanize your criminal protagonist, it’s to have him interact with a little kid. (Pablo has another such encounter in the episode, sprawled on the grass with his children and pointing out cloud-shapes with a bunny puppet on his hand.) Here, the deadpan, businesslike way he introduces himself to David (“My name’s Pablo. Nice to meet you.”) is adorable, and when he commiserates with his child employee for having had to witness the cold-blooded murder of another child (albeit an older one), it’s sincere and affecting. So much of Pablo Escobar’s personal interactions—the ones that don’t end in him murdering someone at least—are like this. Human in a vacuum. So when he explains to the brave little guy that there are bad people in the world, he’s putting the world in black-and-white terms the boy can process. The complexities of the fact that David’s friend was murdered as a message to Pablo, that Pablo put the boy (and continues to put David) in danger for his own ends, that Carrillo’s brutal methods are the government’s desperation tactics to stop Pablo’s reign of terror—all these things are elided for the sake of the message Pablo wants to deliver to a child.

Narcos isn’t dumbing down its message for us to that extent (nominal protagonist Murphy’s laconic narration notwithstanding). In this episode, Carrillo’s return prompts the starkest evidence yet of Narcos’ affirmation of Nietzsche’s dulled-with-overuse “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.” However, the series has always suffered from a lack of sophistication in following through on the ethical issues its story brings forth.

Part of the problem is Murphy. Season two has filtered the action less through his perspective (and has thankfully left his oversimplified narration to mostly historical exposition) but Steve Murphy as a character is simply not a strong enough pole to counter Wagner Moura’s magnetic Pablo Escobar. In the muddled morality play of Narcos, the fact that those chasing Pablo employ questionable methods is a nod toward complexity, but the show is still trafficking in a “good guys vs. bad guys” narrative that never cuts too deeply. That the show’s version of the real-life Murphy is such a naively gung-ho nonentity may be intended as commentary on American foreign policy in Colombia, but that doesn’t make Boyd Holbrook’s Murphy any more interesting to watch.

In this episode, Murphy’s constant complaining that he’s being kept on the outside when it comes to the real down-and-dirty police work finally sees him witness what that means. Maurice Compte’s Carrillo, after his execution of the child spy, takes two captured Escobar men up in a helicopter and summarily pushes them out the door when they won’t talk. Holbrook registers Murphy’s shock with his customary heavenward eye-roll and slouched shoulders, then calls absent wife Connie, confessing “I just needed to hear your voice.” Murphy’s arc has always been leading up to this moment, when he realizes just what he has to become in order to defeat his nemesis, but Holbrook’s Murphy remains discouragingly limp, and Narcos can think of nothing more to do with the moment than have him, wet-eyed, drink and smoke at his desk. (Partner Peña—already familiar with the dark side of police work—registers his ongoing angst by having emotional sex with his favorite prostitute.)

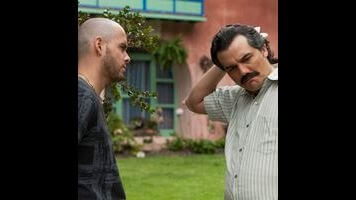

Carrillo’s return signals a change for Pablo Escobar as well, as his resumption of the chase makes Pablo’s hope of returning to La Catedral dim further. “Does that sound like the government is trying to negotiate?,” asks the increasingly frightened but sensible Tata, and she’s right, it doesn’t. Season two will be the story of how the Colombian government—after 15 years living in fear of Pablo Escobar—finally decides that no methods are out of bounds in ending him once and for all. For Wagner Moura, that means introducing notes of uncertainty we haven’t seen before in Pablo’s implacable will. When one of his men tells him of Carrillo’s return, Pablo, as usual, says little, but Moura gives Pablo a tiny hitch in his throat, and draws up his shoulders in a series of weak little jerks. It’s as if he’s attempting to summon the old rage but can barely find the strength to pull it off. And when told of Carrillo ostentatiously pissing on the mural of Pablo that graces the town square, he murmurs an unreadable “mm-hmm” before walking back to where his children await him, making his way across the wide lawn with hunched little steps.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)