On The Beach At Night Alone mixes the painfully personal with the thrillingly unexplained

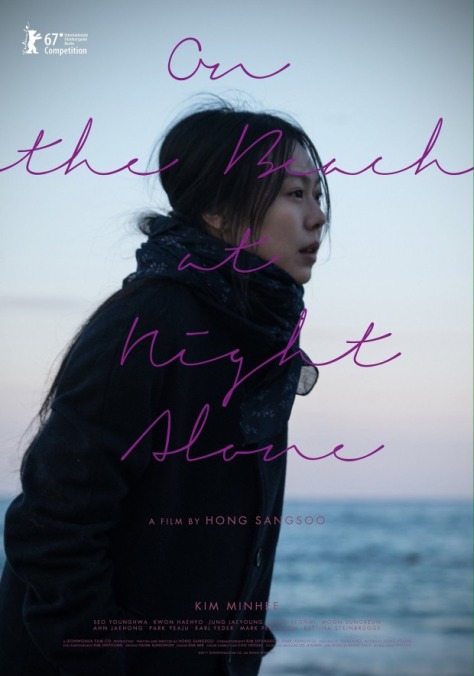

Because most of his films involve characters who are renowned or aspiring film directors, Hong Sang-soo has long been assumed to be working in a largely autobiographical mode. Lately, however, there’s really no way to avoid reading Hong’s personal life into his work, provided that one knows about the scandal—a major media story in South Korea—surrounding Hong’s extramarital affair with Kim Min-hee, who played the female lead in his superb 2015 feature Right Now, Wrong Then (though she’s better known in the U.S. as the Japanese heiress in Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden). Always remarkably prolific, Hong has premiered no fewer than three separate, unrelated features just over the course of 2017; all of them star Kim, and all of them seem to comment on the scandal, either directly or obliquely. On The Beach At Night Alone, which appeared first (at Berlin last February), comes closest to functioning as a sort of apology, albeit to Hong’s lover rather than his wife. It’s also somehow simultaneously one of his most straightforward, emotionally direct movies and the weirdest damn thing he’s ever made.

Ignore a handful of odd intrusions (more on those below), and the story is so simple as to verge on nonexistent. First seen visiting a happily single expatriate friend (Seo Young-hwa) in Germany, Young-hee (Kim) is clearly in a troubled state of mind, and it’s soon revealed that she left Korea in an attempt to get away from a turbulent affair with a married film director (Moon Sung-keun, very pointedly a dead ringer for Hong). She can’t stop thinking about this man, however, and soon—how should one phrase this, given the nature of the transition?—let’s just say for now that she’s back in Korea, meeting with other old friends and reflecting aloud upon her ongoing predicament. Feelings of guilt and anger occasionally burst out at inopportune moments, inspiring reactions from others ranging from comfort to blame. Eventually, by chance, Young-hee is recognized on the beach by crew members who are working on the married director’s current project, leading to a very public, soju-fueled showdown between the two ex-lovers.

That confrontation qualifies as almost blisteringly high drama for Hong, whose characters more typically talk laboriously around whatever it is they’re struggling to express. On The Beach At Night Alone (which presumably borrows its English-language title from Walt Whitman’s poem) operates in a different register from his other films, at once more melancholy—his signature wry humor is almost entirely absent—and more agonizing. It’s a raw, open wound of a movie, in its hunkered-down way, and Hong doesn’t always seem to be wholly comfortable handling emotions that aren’t strictly mediated by social niceties. An early scene in Germany sees Young-hee and her friend speaking stilted English while dining with a couple (Mark Peranson and Bettina Steinbrügge), and the movie as a whole feels similarly stilted. There’s a sober self-consciousness at work here that’s less invigorating than Hong’s usual playful gamesmanship.

He’s still playing games, though, in an unprecedently surreal way. For there’s another “character” in On The Beach At Night Alone: an unnamed man, wearing a dark coat and a knit cap, who has no narrative function yet keeps showing up in bizarre contexts. The first time he appears, in Germany, he simply asks Young-hee and her friend for the time, taking mild umbrage when they can’t help him. (“You don’t have a phone or anything?”) A bit later, they notice him walking toward them and quickly leave the area, though they’re giggling rather than concerned or alarmed. The figure shows up in Korea at a seaside hotel rented by Young-hee and her friends, frantically cleaning the glass doors that lead to the balcony; none of the other characters ever acknowledge his presence, even when he’s opening the door for them. And the leap from Germany to Korea occurs following a remarkable shot in which the camera pans away from Young-hee, alone on the shore, then pans back to find her gone… and then pans in the opposite direction to reveal that she’s being carried over the shoulder of the mystery man. This apparent abduction isn’t mentioned again—the movie actually restarts in Korea, with new credits, as if that had never happened.

These brief, unexplained ruptures—there are a couple of others, possibly including the final scene—are so disconnected from everything else that some reviews of On The Beach At Night Alone don’t even bother to mention them. But Hong clearly threw them into the mix for a reason, even if said reason isn’t remotely clear. One possibility is that this anonymous, vaguely threatening (but perhaps helpful) man represents the married film director, who’s much spoken of but unseen for most of the movie; that hypothesis pretty much collapses, though, once the director himself finally shows up toward the end. Some see the man as Death, but there’s not much to support that idea, unless the scenes in Korea, which constitute most of the film, are meant to be some sort of extremely mundane dying fantasy. Maybe he’s the patriarchy; maybe he’s the public (who won’t stop talking about Hong and Kim’s real-life affair); maybe he’s just Hong’s frustration made manifest. Whatever the explanation, he’s the most arresting component of this exhibitionistic exercise in laundry-airing, which feels as much like personal therapy as it does art.