Once Upon A Time...In Hollywood is Quentin Tarantino’s wistful midlife crisis movie

The first hint that Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood is a more wistful film than it may appear is in its title. Starting with the magic words that mark the opening of a fairy tale, followed by the bridge of a pensive ellipsis, the title evokes the empty, bone-deep ache that underlies all nostalgia, a longing for a half-remembered moment in time that may never have really existed at all. If any contemporary film director’s work stands up to such a granular reading, it’s Quentin Tarantino’s; in this film, as in all his others, he breaks down a place and time—in this case, Hollywood, 1969— and rebuilds it in his own movie-obsessed image, each deliberately placed poster and casually dropped reference one piece of a cryptic puzzle. Here, however, the writer-director’s own yearnings and anxieties are closer to the surface than usual.

This is Tarantino’s most personal film in decades, and the longings expressed in it flow from who he is as a person: an established middle-aged white guy confronting his own impending irrelevance. That exact prospect eats away at the film’s protagonist, Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), a fading Western TV star whose diminishing celebrity has forced him to contemplate the unthinkable for an actor of his caliber: going to Rome to star in “Eye-talian” Westerns. Rick still lives the lifestyle of a man in his 20s, but now those blotto nights alone in his Hollywood bachelor pad leave him hungover, melancholy, and unable to remember his lines on the set of whatever B-grade TV show he’s guest starring on that week.

Rick’s most lasting relationship has been with his stuntman/driver/chief enabler, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), whose reckless driving betrays a dangerous violent streak underneath his bright Hawaiian shirts and cocky comebacks. Rick and Cliff are openly contemptuous of hippies—DiCaprio, puffy and red-faced, screams at a car full of them wearing a half-open bathrobe and clutching a pitcher of margaritas at one point—and of Mexican people. Their conservative crankiness is a clear reflection of their insecurity about their place in a rapidly changing film industry (and world); it’s an unflattering aspect of their personalities that’s reflected in DiCaprio’s vulnerable, admirably pathetic performance as the past-his-prime Rick.

The relationship between Rick and Cliff is at the emotional heart of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood, which openly pines for the carefree irresponsibility of youth. Rick doesn’t want to leave behind the good times with his best buddy, and the camera zeroes in on closeups of drinks being poured, shaken, cracked open, and drunk with the focused yearning of a newly sober alcoholic trying to keep their cool at an open bar. The tension between the rose-colored perspective of an older man reminiscing about the good old days and the explosive restlessness of actual adolescence come together in the film’s sharp right turn of a final act, as Mick Jagger rasping, “Baby, baby, baby, you’re out of time,” over footage of classic Hollywood neon lulls the viewer into a melancholy reverie that’s abruptly disrupted by a Molotov cocktail of a climax.

Ironically, even as it contains this seemingly personal streak of sadness and sentimentality, Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood is relatively short on Tarantino’s regular filmmaking tics. One signature accounted for here is his handpicked casting choices, some—Kate Berlant working the box office at a movie theater, Kurt Russell and Zoë Bell as married stuntpeople—more successful than others. (Lena Dunham’s presence as a maternal Mansonite is as discordant as feared.) Historical villains Roman Polanski (Rafal Zawierucha) and Charles Manson (Damon Herriman) make only brief appearances, which seems to point toward a desire on Tarantino’s part to put a sunnier polish on the ’60s in his personal rewrite of history. With this in mind, however, the film’s choice to turn Bruce Lee (Mike Moh) into a comedic punchline is baffling, especially considering Tarantino’s visual tribute to the late martial-arts master in Kill Bill: Vol. 1.

Tarantino’s approach to dialogue, meanwhile, is noticeably different in this film. The filmmaker, who was born in 1963, often writes characters obsessed with the pop culture of his youth. Here, that pop culture is just part of the oxygen everyone breathes, living as they do in the Hollywood of 1969. So instead of the characters having a long conversation about the 1970 Joe Namath/Ann-Margret biker flick C.C. And Company, the trailer plays before the matinee of The Wrecking Crew that Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) impulsively attends so she can watch herself on screen. Movie posters and marquees, advertising projects both real and fictional, linger in the background throughout. Cliff literally lives in the shadow of the Van Nuys Drive-In. This is Tarantino’s Eden, the unspoiled garden when the things he loves don’t have to be sought out or championed because they permeate every aspect of life. The sense of blissful immersion extends to the film’s costuming and production design, both of which are as meticulous as one might expect.

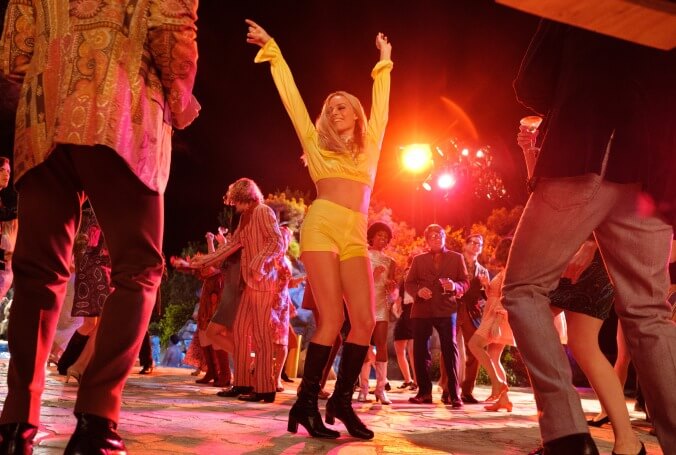

Of a piece with the film’s more organic approach to blaring, kitschy-cool pop music and deep movie geekdom is its freewheeling plotting, which stays loose and languid until hitting the fast-forward button in the last half hour of this two-and-a-half hour film. Most of Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood’s runtime follows Rick, Cliff, and Sharon on separate adventures on the fringes of the movie industry, with “It girl” Sharon vaguely posited as the counterpoint to Rick’s fading clout. Much was made of Robbie’s lack of dialogue after the film’s Cannes screening, and it’s true that although she has a good amount of screen time, she doesn’t say all that much. That doesn’t necessarily equate to a flimsy role, but there’s really only one scene where Sharon’s internal light truly shines: the sequence where she sneaks into a theater to watch one of her films incognito, beaming with pride and satisfaction behind huge glasses as she soaks in the audience’s laughter and applause. The rest of the time, she’s as ephemeral of a character as the dead-eyed Manson followers who hang menacingly around the fringes of the film.

Tarantino’s longtime editor, Sally Menke, died in 2010, and her absence is still palpable. But though Menke’s assistant, Fred Raskin, stumbled with Django Unchained, he comes into his own with Once Upon A Time, indulging in high-wire experiments that further unmoor the film from conventional plotting. Entire sequences are cut in as flashbacks mid-scene, as when Cliff’s idle remembrance of Rick’s comment about him knowing better than to ask stunt coordinator Randy (Russell) for work leads to an extended scene of Cliff picking a fight with Bruce Lee—and, quite improbably, winning. (If, indeed, that’s what really happened; in a movie obsessed with image and memory, Cliff may not be the most reliable of narrators.) But the Arrested Development of it all is most acutely felt in the conversations about Rick Dalton and his filmography, scenes heavily seasoned with quippy cutaways to footage of DiCaprio in fictional movies like The 14 Fists Of McLusky and Operazione Dy-no-mite!, alongside actual ’60s classics like The Great Escape.

The moment that gives us perhaps the clearest view of Once Upon A Time’s complicated relationship with fame and a life lived through pop culture comes midway through the film, as Rick struggles through a scene opposite a younger cowboy star (Timothy Olyphant) on the latter’s Western series. We know that we’re watching the TV show within the film because DiCaprio’s repeating dialogue we watched him practice earlier. But the scene is shot in the same aspect ratio and cut with the same rhythm as the larger film itself. We see neither crew nor cameras, and the only indication that this isn’t “really” happening are voices offscreen feeding Rick/DiCaprio his lines—that is, until Rick nails the scene. Suddenly, the spell is broken, the camera pulls back, and the director, crew, and equipment all appear on the sidelines. For Rick—and, one assumes, for Tarantino—movies (or, in this case, TV) and life have become interchangeable, and failing at one essentially obliterates the other. What will both of them do, Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood wonders, when their moments of triumph are gone?

For thoughts on, and a place to discuss, plot details we can’t reveal in this review, visit Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood’s Spoiler Space.