One last time, Twin Peaks takes your hand and walks you into the dark

“Once we cross, it could all be different.”

“What is this?” asks Dark Coop, transported to Twin Peaks. “What the hell?” asks Hawk, running into Truman’s office after hearing gunshots. “Dougie is Cooper? How the hell is this?” Gordon Cole yells in his makeshift command center. “What’s going on?” asks James Hurley as he listens to Naido chirping in her nearby cell. “What the fuck just happened?” asks the good ol’ boy who drew a gun on the wrong man in an Odessa diner. “What’s going on?” Carrie Page (Sheryl Lee) wonders when the FBI agent at her door keeps calling her Laura Palmer. “What’s going on around here?” Bobby Briggs asks, striding into Truman’s office after the excitement has passed.

When Bradley Mitchum says, “Took the fuckin’ words right out of my mouth!” he’s talking to Bobby Briggs, but he could be replying to any of those questions, or speaking for viewers. “The Return: Part 17”sets itself up as the answer to the questions Twin Peaks poses. Then “The Return: Part 18”smashes all those answers to pieces and poses more staggering questions. “Who killed Laura Palmer?” was a mystery that captivated a generation, but it was a question with an answer. “How’s Annie?” was a question that didn’t ask for an answer; it was a phrase parroted by a spirit masquerading as a man. “What year is it?” reveals how that man, finally returned to this world, has lost grasp of it in his quest to do good.

Much of Twin Peaks’ mythology revolves around a gold ring with a carved green stone. That ring is a closed circle, and the figure 8 that Phillip Jeffries conjures from its carving might as well turn sideways to form an infinity symbol. David Lynch loves a time loop, and Twin Peaks: The Return’s finale creates a time loop that manages to break the repetition that phrase implies. As Dale Cooper warns Diane—the true Diane, now that they’ve found each other—“Once we cross, it could all be different.” It is, and it isn’t.

David Lynch and Mark Frost have done it to us again. “Part 17” and “Part 18” make the events of the series, stretching over more than 25 years, into a circle that loops around to create a mystery bigger than the one that started the whole thing. They’ve told a story with no end; they’ve posed a question that couldn’t satisfy us even if they offered an answer—which they do not.

“Part 17”and “Part 18” are full of hints that the two-part finale will eschew traditional narrative and the expectation of a clear conclusion even more than most Twin Peaks episodes. In the opening of “Part 17,” Gordon Cole apologizes to his colleagues for keeping from them the crucial plan at the center of their investigation, finally ’fessing up, “And I don’t know at all if this plan is unfolding properly.” On the phone, Agent Headley (Jay R. Ferguson) reassures Gordon, “Director Cole, we got it all. The whole story.” By that, he means they know where Douglas Jones was, but not where he is, how he got there, how he recovered so quickly, why he’s been doing what he’s doing, or even who he is.

The battle in the Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department highlights the futility of relying on traditional story structure in telling a tale as abstract and enigmatic as this. Events have conspired to bring an unlikely group together in the cells just so that Freddie and his pile-driver fist can save Deputy Andy from dirty cop Chad. That means Andy can lead Freddie, James, and Naido (who is the disguised embodiment of the real Diane Evans) upstairs just in time for the real Dale Cooper to arrive—and just in time to battle Bob.

Like the keys Chad’s stashed away in his heel or the Great Northern room key Dale Cooper retrieves from Frank Truman, this spectacular collision of powers seems for a moment like it will be the key to everything. There’s a tidy plan in place, and its very tidiness makes it anticlimactic. It has to be an anticlimax, and not only because it occurs less than 30 minutes into the two-hour, two-episode finale broadcast.

The tension between good and evil that has inhabited Twin Peaks can’t be reduced to a fistfight, even if it’s a fight between a man of supernatural power and a malignant mass of evil. And it can’t handed off to a minor character, no matter how colorful his origin story. In “Part 17,” Freddie meets his destiny, but his destiny isn’t the key to Twin Peaks or the answer to its mysteries. It’s a respite from terror, a breathing space that gives Dale Cooper time to consider his next step.

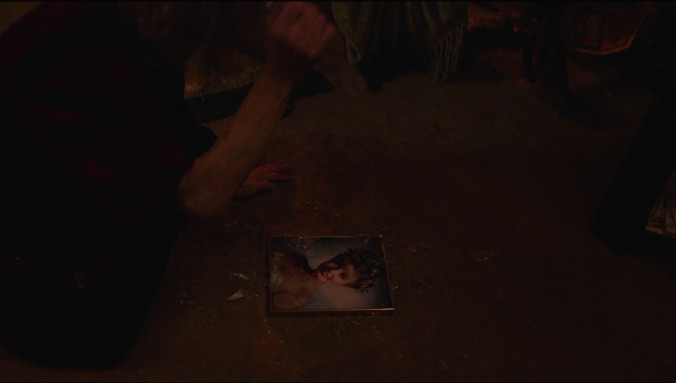

Maybe the most vivid example of Twin Peaks throwing off its history and the expectations that come with it isn’t spoken in words. It’s the image of Sarah Palmer picking up the portrait of Laura and smashing it in a frenzy. Laura’s portrait haunts Twin Peaks: in her parents’ living room, in the trophy case at the high school, in the evidence boxes holding the cold hard facts of her murder. Sarah’s assault on that sweet, smiling photograph feels like a rebuke of the nostalgia haunting Twin Peaks, and of the expectations that nostalgia demands.

Before the epic clash in Frank Truman’s office, Chad holds Andy Brennan at gunpoint, taunting him, “If it isn’t the great good cop, Deputy Andy, come to save the day!” Chad’s a criminal and a fool and a lout, but his mockery has some weight, and it isn’t just Andy who’s the butt of it. It’s thrilling to see Special Agent Dale Cooper finally waking up to himself, to see him regain command of himself, to see him traverse time itself to take young Laura Palmer by the hand and lead her through the darkness, away from her destiny. But Dale Cooper’s grasp on himself (and on the mysteries of the universe) is as uncertain as his grasp on Laura’s hand. They all slip away with terrible speed. As Phillip Jeffries says, “It’s slippery in here.”

By the time Special Agent Dale Cooper is showing Carrie Page to his car, he’s already failing to ask the right questions. It’s Carrie, not Cooper, who spots a car driving close behind them; after she asks if they’re being followed, his worried eyes flicker to the rearview mirror until the car passes harmlessly. At the door of the house we know as the Palmers’ home, Carrie looks at Cooper with increasing apprehension as he fumbles his way through uncertain questions, barely seeming to register the answers. (Twin Peaks completists will recall that the original Mrs. Tremond was also known as Mrs. Chalfont.)

This was never the story of The Great Good Cop Come To Save The Day. The day can’t be saved, not now, maybe never. How’s Annie? Where’s Laura? What year is it?

Dale Cooper tries, and fails, to save Laura Palmer from the death she’s already suffered; he tries, and fails, to revisit a moment that has passed. Margaret Lanterman knew better. The Secret History of Twin Peaks tells us she opened her eulogy of Robert Jacoby (Lawrence’s brother) with the words, “This is now. And now will never be again.” She exhorts the collected mourners to live in the moment, to breathe in the full physical experience of it as they breathe in the air around them, and to have faith that the next moment will follow this one just as they have faith that their next breath will follow this one.

“What do we do now?” Diane asks Dale (or Linda asks Richard) at the hotel where they rest after they’ve crossed over at a designated point, a spot rich in electricity, a place and a process that has the power to change everything. “You come over here to me,” he responds. And maybe that’s the most important answer to the question, asked over and over in various forms through these last two episodes: What happens now? What happens now is that we try to connect, we try to overcome trauma and tragedy to trust each other and to trust that life will go on, or that its ending is beyond our control.

That’s a hard lesson for humans to accept. We try to tell make a coherent story of something that can’t be reduced to a simple through-line. We try to make tidy endings where none exist. Life is a mess. It’s a thrilling, disturbing, tedious, hilarious mess. It’s a glorious tangle of sense and nonsense, of coherence and incongruity. So is Twin Peaks. Maybe that’s why we see the newly created Dougie reunited with his family, but there’s no closure for Audrey Horne. It’s a bitter, brutal truth that closure is a luxury, not a guarantee.

Margaret’s eulogy for Robert offers a hint of hope that even Dale Cooper and Laura Palmer—or Carrie Page—can cling to in this confusing world in which at least one of them is misplaced. “There is change,” the Log Lady told Robert’s friends and family years ago, “but nothing is lost.”

Stray observations

- “Listen to me,” Gordon Cole tells his colleagues before a long, long pause. “Now, listen,” Dale Cooper instructs Gordon and Diane at that mysterious door at the Great Northern. “I am the arm and I sound like this,” the bulbous head of a flailing, flickering tree-or-limbic-system repeats to Dale Cooper in the Red Room. The sound of Twin Peaks is as crucial as the visuals. If you haven’t read Clayton Purdom’s examination of that sound, now is a perfect time to do it.

- Naido being reduced to a placeholder for Diane is another example of Lynch’s clumsy sidelining of non-white characters. In this case, she’s not even a character, but a symbol of a character.

- The real Dale Cooper: “We’re just entering Twin Peaks’ city limits. Is the coffee on?” Evil Dale Cooper, offered a cup of coffee: “No, thanks, I’m all right.” Harry Truman would have known that wasn’t his friend Coop in an instant.

- Sheryl Lee’s bravura performance in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me demonstrates, among other things, that she possesses one of the most terrifying screams in show business. That scream is deployed to dreadful effect here, as Laura slips from Dale Cooper’s grasp in the forest, again as she’s lifted from the Red Room, and finally as she hears Sarah calling “Laura?” at the end.

- Very few characters in television history could wear a pink chenille robe as if it were a mink stole. Laura Dern’s Diane is one of them. Dern brings subtle layers to Diane as effectively as MacLachlan does to the many Coopers. The real Diane is just as strong, as capable, and as flamboyantly stylish, but her warmth and vulnerability show how brittle and mannered the doppelgänger is.

- That’s the end of this long-awaited, unexpected, unfathomable, intuitively elegant season. It’s been a joy and a challenge to cover Twin Peaks: The Return. Thank you for reading.