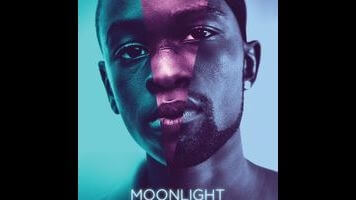

One of 2016’s best, Moonlight unfolds a coming-of-age story with poetic grace

Three actors, three ages, one soul: Barry Jenkins’ beautiful, sensitive Moonlight tells a coming-of-age story in passages, each possessed of enough stand-alone power to operate as a wonderful short film, even as the whole proves much greater than the sum of the parts. After the time-lapse miracle of Boyhood, any movie hoping to credibly depict someone growing up on screen has its work cut out for it. But watching Chiron, the main character of Moonlight, change from a bullied 9-year-old boy (Alex R. Hibbert) to a gawky teenager (Ashton Sanders) to a quiet, muscular man (Trevante Rhodes), it’s easy to believe we’re seeing the same person throughout—the same shy and taciturn kid, uncomfortable in his own skin, living in his own head. The actors don’t look much alike, but they create a continuity of performance: a whole person in spectrum.

Chiron is poor, black, and gay (though the last of those isn’t something he seems comfortable saying aloud), and one could mount a case for Moonlight on grounds of representation alone: Rarely does American cinema even address this kind of character, let alone with such poetic grace. Jenkins, returning to feature filmmaking some seven years after Medicine For Melancholy, adapted the script from a short, autobiographical stage play called In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, rearranging its nonlinear plot into three distinct chapters. Both he and the play’s author, Tarell Alvin McCraney, grew up in the Liberty City housing projects, where Moonlight is set. Their shared background seems crucial to the film’s specificity: It presents a very different Miami, a more hardscrabble one, than the neon nightlife usually put up on screen.

From its fantastic opening shot, in which the camera pivots around a parked car at a drug corner, Moonlight acknowledges the destructive cycles—of poverty, of crime, of toxic self-image—that too many kids get sucked into. At the same time, the film sidesteps stereotypes. Chiron’s single mother, Paula, shatteringly portrayed by Naomie Harris, may be a junkie, but she’s no one-dimensional monster; creating her own devastating arc across just a handful of scenes, Harris shows glimmers of the better parent she’s trying to be. And then there’s Juan (a fantastic Mahershala Ali), the drug dealer who discovers young Chiron (Hibert) hiding in a vacant building and starts looking after the boy. A viewer might doubt the man’s motives (is he grooming another kid for the corner?) were it not for the great paternal warmth Ali conveys—especially during the deeply moving scene where Juan and his girlfriend (Janelle Monáe) talk to Chiron, with honesty and without judgment, about his sexuality.

The question of what it really means to be a man hangs over Moonlight, and Jenkins gets into the expectations put on boys—and that boys put on each other—to act, talk, and feel a certain way, to always fight and to never cry. The film jumps, in its second chapter, into the social battleground of high school, where Chiron (now Sanders, playing a chronically self-conscious teen) weathers harassment from his peers, who can tell he’s different from them. But he also gets closer with Kevin (Jharrel Jerome), introduced as a young boy in the previous segment, and the film shows how their bond—a friendship teetering on the edge of something more—is both defined and threatened by what they’ve been taught about masculinity. These scenes ache with feeling, sometimes spoken, sometimes conveyed through nothing but the body language of the actors.

Moonlight reaches for big insights on identity, race, culture, and sexuality, but never at the expense of the small, heartrending character study at its center. In that way, it’s a natural evolution from Medicine For Melancholy, which nestled a dialogue about gentrification into a romantic two-hander. But Jenkins has made a momentous leap forward as a filmmaker. He does more than just expand and rearrange his source material; he also gives it an urgent cinematic rhythm, a heartbeat. Some of that comes from the soundtrack, which mixes choice cuts (like Boris Gardiner’s “Every Nigger Is A Star,” sampled on the opening track of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly) with the emotive whine of Nicholas Britell’s score. But it’s also in the nervous, circling movement of James Laxton’s cinematography as well as the vibrant shades of blue—the paint on a car, the dye on a shirt, the natural hue of the ocean—with which he colors Chiron’s world.

“You’ve got to decide who you want to be,” Juan tells Chiron. “You can’t let anyone make that decision for you.” But Moonlight floats the idea that we’re shaped most by the people in our lives—and by the last act, when Rhodes has taken over the lead, the resemblance between the hulking adult Chiron and the man handing him that advice has become unmistakable. This final passage, when he reconnects with someone from his past, is entirely Jenkins’ invention, and it’s one for the ages: Channeling the great Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai, Jenkins floods a bittersweet reunion in warm light, warm conversation, and glorious jukebox sentiment. “It seems so good to see you back again,” goes the song. Moonlight lets us see Chiron, to see his silent heartache written across three different faces, and that seems a hell of a lot better than good.