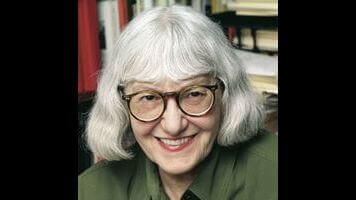

Cynthia Ozick doesn’t write sentences so much as she unleashes fireworks of prose into existence. Her writing—especially her nonfiction work, of which this new book is merely the most recent collection—manages the rare feat of being both lyric and intellectually stupendous, possessed of logophilic beauty and rigorous structure in equal measure. Reading her essays, it’s easy to be taken with the smooth elegance of her arguments, but there is a razor-sharp wit behind the delicately crafted curlicues of insight and analysis. At 88 years old, she’s lost none of her edge, and woe indeed to those who find themselves in the crosshairs of a negative Ozick judgment.

The critic’s job is to relate the work to other work, to situate it among the history and bedfellows of its genre and ideas, to “read the medium through the medium,” so to speak. (Hence, a book review such as this one falls into the purview of writing she testily accepts as a banal necessity of literary culture: Brief and reductive assessments of an isolated work, as though each book reviewed were “a wolf-child reared beyond the commonality of a civilization.” Forgive us our trespasses, Ms. Ozick.) Taking aim at the internecine squabbling of contemporary hand-wringers like Jonathan Franzen and Ben Marcus, who bemoan the status quo of serious literature’s place in our society, Ozick convincingly argues that the concern of critics should not be who still reads, or what they read, but why:

And why really? To catch hold of the tincture and pitch of the hour, the why of the moment, the why of what led to the moment, the why of what may come o the moment, the frights and the fads, the hue and the cry, they why of what is honorable and what is not, the why of what is true and what is lie. It is the why that implicates and judges readers, and reviewers, and bestseller lists; and novelists. No novel is an island, entire of itself. And it is again the why that tells us how superior criticism—the novel’s ghostly twin—not only unifies and interprets a literary culture, but has the power to imagine it into being.

With such declamations are the manifestos of future generations of literary scholars born.

From there, Ozick delves into the world of fellow critics and era-transcending artists—“figures” is the preferred term she takes from Lionel Trilling, one of her most enlightening subjects here—before expanding her scope outward, to perform examples of the kind of critical essaying she calls for in that opening salvo. Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and W.H. Auden all get penetrating expositions of why their work outstrips their own limited concerns. Not all of them are equally illuminating (if you’re unfamiliar with Malamud’s writing, nothing here will give you much evidence to support her claim for his greatness), but they all ring with the force of a brilliant mind who has made her evaluations and is ready to defend them in the most commanding language possible.

She considers various biographies, critical histories, and novels, all while simultaneously compiling her own syllabi and indexes in a manner suggesting Ozick’s take on the material would doubtless supersede that of the fellow critics upon whom she turns her critical eye. This suspicion endures even when—as in the case of Reiner Stach’s three-volume biography of Kafka—she finds the results to her liking. In sections respectively organized as “Fanatics” (Kafka and Jewish-American poets who wrote in Hebrew), “Monsters” (Rilke, Rabbi Baeck, Harold Bloom), and “Souls” (William Gass, Martin Amis, H.G. Adler), Ozick locates the vital pulse of these authors’ respective relationships to literature, inlaid against such larger themes as the nature of writers’ socialized being, or in the case of her hardy “souls,” the Holocaust. (This last section begins with one of the most succinct and insightful considerations of Adorno’s famous “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” dictum this reader has ever seen.) Each section fairly seethes with the turbulent rumbling of her mind, the mere promise of which should send curious readers straight to the bookstore. Rarely a page goes by that doesn’t contain at least one sentence so elegantly conceived, it forces a pause of admiration and reflection. And that is a writer’s true measure, critic or no.