One of punk’s true originals, Germfree Adolescents is as fresh today as it was in 1978

In July of 1976, Marianne Joan Elliott-Said, a Scottish-Somali girl from London’s inner-city Brixton district, celebrated her 19th birthday by going to see the Sex Pistols. Marianne dropped out of school at age 15, and had spent the last few years drifting between music festivals, crash pads, and recording studios in an attempt to get her music career off of the ground. She had even released a single, a novelty reggae song called “Silly Billy,” with Donna Summer’s U.K. distributor, GTO Records. But she was frustrated—frustrated with not being taken seriously as a musician, and frustrated by the racism, sexism, and classism that seemed to make achieving her dreams impossible.

It was the perfect frame of mind in which to see what was, at the time, England’s most notorious band. Like the many future punk and post-punk figures—members of the Buzzcocks and Joy Division, Morrissey and Mark E. Smith—who’d seen the band at its legendary Manchester gig the month prior, Marianne was so inspired by the Pistols’ do-it-yourself spirit that she decided to finally form the band that she’d been thinking about. She immediately jettisoned her hippie style and took on the stage name Poly Styrene, a cheeky nod to the disposable society she would go on to satirize in her lyrics. She then placed ads in a pair of music papers looking for “YOUNG PUNX WHO WANT TO STICK IT TOGETHER.” That call was answered by saxophonist Lora Logic, bassist Paul Dean, drummer B.P. “Big Paul” Hurding, and guitarist Jak Airport, and X-Ray Spex—or at least, its initial incarnation—was born.

From the first track on X-Ray Spex’s debut album, Germfree Adolescents, it’s obvious the band had a well-rounded set of influences. Jak had come from the glam-rock scene, and played spunky power chords that straddled the (admittedly blurry) lines between power-pop, new wave, and punk. (His rock ’n’ roll roots are especially evident in the guitar solo that opens the arch ode to apathy “I Can’t Do Anything.”) Paul’s steady personality was reflected in his rock-solid, dub-influenced bass lines on “Warrior In Woolworths” and “Germ Free Adolescents,” ballads that broke up the monotony that afflicts so many punk records. B.P., who liked to drive Poly around London in his beat-up white van, kept things moving on stage, too, pushing Lora’s staccato saxophone and Poly’s howling vocals forward with rapid drum fills and lots of cymbal on more uptempo numbers like “I Am A Poseur.”

Before long, Lora left X-Ray Spex. The official line was that she needed to concentrate on her schooling, but she says she was kicked out for stealing too much of Poly’s spotlight. She went on to form her own band, Essential Logic, and play saxophone for artists as diverse as The Raincoats and Boy George. (She also joined the Hare Krishnas, and reunited with Poly at George Harrison’s Hare Krishna manor in the mid-’80s.) Lora was replaced by a former male model named Rudi Thomson, who had a bit of a complex about the session musician who was brought in to overdub his parts on several tracks of Germfree Adolescents. And in Rudi’s defense, although he and Lora shared a certain, let’s say, lack of concern for tuning, his sax solo on “I Live Off You” sounds quite professional. Those tracks, like every X-Ray Spex song featuring saxophone, were based on arrangements Lora had worked out before leaving the band.

X-Ray Spex weren’t revolutionary fellow travelers like the Sandinista fans in The Clash, nor were they indiscriminate nihilists like the Sex Pistols. X-Ray Spex were political in the way that Marshall McLuhan was political, less concerned with whoever’s in power at the moment than the capitalist system, and the insidious ways it controls ordinary peoples’ lives. This dystopian, almost sci-fi streak is most prevalent on “The Day The World Turned Dayglo”; opening with chugging power chords and a wailing sax riff, the song lives up to its B-movie title with Poly’s vision of a world where even the trees are artificial: “The X-rays were penetrating / Through the latex breeze / Synthetic fiber see-thru leaves / Fell from the rayon trees.”

Despite its bleak outlook, the song is a catchy, singalong number, typical of Poly’s “perverse” embrace of the soulless consumer culture she dismissed with one word: “Plastic.” As she told NME in a 1978 interview, “The weird thing about all the plastic is that people don’t actually like it, but in order to cope with it they develop a perverse kind of fondness for it, which is what I did. I said, ‘Oh, aren’t they beautiful because they’re so horrible.’” Poly embodied plastic as an aesthetic, reveling in the throwaway relics of consumer culture rather than rejecting them. She wore braces, loaded herself with cheap costume jewelry, dyed her eyebrows pink and green, and dressed in gaudy, mismatched neon outfits designed to make her look as asexual as possible.

She also sold jewelry made from discarded trash and tire chain at her Poly Styrene boutique on King’s Road in Chelsea, then ground zero for the punk movement. There, she amused herself and her friends selling her aggressively kitschy creations to fashion victims at a huge markup. The boutique didn’t last long, but it did lead to X-Ray Spex getting its first regular gig: a residency at Man In The Moon, a pub just down the street from Poly’s boutique where the band worked out much of its material on stage in the first few months of its existence. Clubs and labels were eager to fill their rosters with this new wave of punk bands in 1976, and so after only six rehearsals X-Ray Spex booked a gig at the Roxy, the London punk club famous for its fashionable clientele and seedy SoHo milieu. One year later, in September 1977, X-Ray Spex’s first 7-inch single was released on Virgin Records.

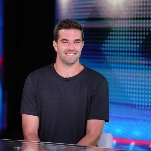

The scenesters at the Roxy and journalists who tippled at Man In The Moon were immediately taken with Poly: a biracial woman in a majority-white-male scene, a rock ’n’ roll frontwoman who actively rejected the idea of sex appeal, and a girl who spoke in a whisper but was an unstoppable hurricane of a singer. On stage, Poly Styrene was one of the all-time great punk-rock belters, her voice ranging from commanding to strident but always impossible to ignore. Unlike basically everyone else in punk, she was a trained singer who knew how to put power behind her vocals. But she wasn’t a slick, calculated pop singer putting on a trendy mask, either. She often goes out of tune—which matches the similarly discordant saxophone, really—and her voice would sometimes grow hoarse and break as she reached for high notes, particularly on quieter ballads where she couldn’t rely on lung power to propel the notes forward. Without her, there’d be no Kathleen Hanna or Corin Tucker, two singers whose open-throated styles are very much in the Poly Styrene mold.

Poly Styrene intuitively understood the performative nature of femininity, telling one interviewer that her fashion was “sort of an illusion.” But there was also a shyness and unguarded girlishness about her that made her fascinating to music journalists. As NME wrote in its 1978 interview with Poly:

The conventional discipline of New Wave performing styles has eliminated a lot of the old posturing only to replace it with a new set of anti-postures, which are ultimately no less stylized, but Poly cuts through all the bullshit just by bopping round the stage with that mile-wide grin, free from any hint or taint of artifice, just having a flat-out good time, a genuine, communicable enjoyment of the right here and right now.

Similarly, asked if she was a rebel in a November 1977 interview with the Australian music show Countdown, she replied with a soft giggle: “Yes, I suppose I am a bit.” But don’t mistake that soft-spoken nature for naïveté. In that same segment, the interviewer condescendingly asks Poly if she formed her own band, writes her own songs, and put together her own outfits; her responses are the cutting sort of polite, dismissive and clearly bored.

Poly’s caustic lyrics also closely intertwine feminism and anti-consumerism, so much so that her most famous song, “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!,” was adopted as a feminist anthem even as she emphasized its broader message in interviews. (“It’s about any form of slavery. It’s against that, saying ‘Oh bondage up yours, fuck off’ to all of that,” she said in 1977.) But Poly’s lyrical feminism isn’t always implicit. “Art-I-Ficial” expresses her demented desire to be one with the consumer zeitgeist: “I want to be Instamatic,” she sings. “I want to be a frozen pea.” And in the second verse, Poly sums up the intersection of capitalist power structures and misogynist oppression: “When I put on my makeup / The pretty little mask not me / That’s the way a girl should be / In a consumer society.”

This theme of scrubbing and spraying the unruly female body into a state of sterility/safety, and the fear driving those purchases, comes up again in the title track on Germfree Adolescents, a love ballad of sorts about a teenage girl who tries to fend off the dangers of womanhood with aerosol deodorant and obsessive tooth brushing. And those fears never go away, nor do the products designed to alleviate them. As Poly sings on “Age,” the B-side to the “Germ Free Adolescents” 7-inch that was added to the Germfree Adolescents album for its belated 1991 U.S. release: “Darling, am I looking old? / Tell me, dear, I must be told / You know it’s a million-dollar fear / If lines creep in over here.”

That disdain for consumerism and conformity also drives X-Ray Spex’s other major lyrical through-line: Its righteous crusade against poseurism. For even as Poly defiantly proclaimed, “I am a poseur, and I don’t care” on “I Am A Poseur,” that may have been another case of “perverse fondness” similar to her love of all things plastic. As she told NME, “In a way, I think posin’ is a laugh. But just dressing up and having a laugh—and only providing you know the difference between the reality of it and the fantasy of it.”

More common are lyrics critiquing the growing conformity within the punk scene, which by the time Germfree Adolescents was released in 1978 had crystallized into a sea of kids in identical fetish gear and Mohawk hairdos. On “Identity,” inspired in part by watching a member of the Sex Pistols’ so-called “Bromley Contingent” slash her wrists backstage at a club, Poly takes the punk crowd to task, asking, “Did you do it for fame / Did you do it in a fit / Did you do it before / You read about it?” On the squalling “Obsessed With You,” she condemns the wannabes further: “You are just a victim / You are just a find / Soon to be a casualty / A casualty of time.” It all comes together on “Plastic Bag,” an unofficial statement of intent that alternates between frantic guitar thrash and soft, jazzy saxophone bridged by one key phrase: “Apathy’s a drag.”

In public, Poly Styrene and her bandmates put forth a playful image of happy pigs heading to the self-aware synthetic slaughter. But in private, the band’s meteoric rise to fame was starting to weigh on its leader. In 2017, Poly’s daughter, Celeste Bell, wrote in The Guardian, “I wonder if my mum might have had a happier life if she hadn’t had that level of fame,” a question that’s all but answered by this classic introvert statement Poly made in 1978: “You feel all the time that people are draining you, draining off your energy all the time until you think, ‘Blimey, I haven’t got anything left to give. Leave me alone.’”

Then there was the trauma that occurred while X-Ray Spex was on tour in 1978, which so affected Poly that she shaved her head upon returning to London. The closest she ever came to confirming the nature of the trauma was in a 2005 interview with John Clarkson, where she said, “I had said in the press right at the beginning that if I became a sex symbol I would shave my head. I wasn’t a sex symbol, but that traumatic experience was of a sexual nature. I had a breakdown and I went down to John Lydon’s house and shaved my head. Everyone there thought that I was mad, but it was just some kind of symbolic thing.”

The stress of fame, tabloids, and that buried trauma exacerbated Poly’s existing mental health issues, which included intense mood swings and hallucinations. One of her fixations was on Nazis, who show up in a pair of songs on Germfree Adolescents—“Genetic Engineering” and “Plastic Bag,” where she sings, “I dreamed I was Hitler / The ruler of the sea / The ruler of the universe”—but the thing that finally broke her bandmates was when she told them she saw a UFO one night after a gig. “[I saw] a Day-Glo UFO in Doncaster one night after a concert. It was a bright ball of luminous pink, made of energy—like a fireball. Everyone else thought I’d lost the plot,” she told The Independent in 2008.

And so, by 1979, it was all over, as Poly quit the band to focus on her mental health after being misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. (She wasn’t correctly diagnosed with bipolar disorder until 1991.) In 1980, she released her first solo album, Translucence, a radical departure from X-Ray Spex inspired by the gentle vibrations of Poly’s visions and the Hare Krishna temple where she had started spending significant amounts of time. The spiritual acceptance and peace Poly found with the Hare Krishnas would profoundly influence the music she released as a solo artist, although her last album, 2011’s Generation Indigo, did show flashes of the old Poly on the bubbly, Le Tigre-esque “Virtual Boyfriend” and “I Love Ur Sneakers.” And although Poly, Lora, and bassist Paul Dean reunited to record a second X-Ray Spex album, Conscious Consumer, in 1995, the moment had passed, and a planned trilogy of albums never came to be.

Poly Styrene died of breast and spinal cancer at the young age of 53 on April 25, 2011, seven years after X-Ray Spex guitarist Jak Airport also succumbed to cancer. As so often happens, it wasn’t until after Poly’s death that she, and X-Ray Spex, were lifted from the margins of punk history and lauded as just as influential—perhaps even more so, especially for women of color looking for role models in the movement—as the Pistols and The Clash. Last year, Celeste Bell successfully crowdfunded a documentary about her mother’s life called Poly Styrene: I Am A Cliche, which went into post-production last week. Forty years after the release of its debut album, X-Ray Spex still has a lot to teach us plastic people of the future.