One week after releasing his epic, indie director Patrick Wang offers the thinner Grief Of Others

Patrick Wang doesn’t just write, direct, produce, and sometimes star in his own films. He self-distributes them, too—a choice made out of a desire for control, perhaps, but also maybe out of an understanding that his work doesn’t fit any boutique “brand,” any Fox Searchlight yellow or moody A24 blue. Born and raised in Texas, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, Wang jump-started his career with the languid custody drama In The Family, which was as unconventional in its route to theaters—bypassing the festival circuit, selling tickets through grassroots means—as it was in its evenhanded approach to potentially soapy material. His most recent movie, A Bread Factory, is even tougher to pigeonhole: It’s a four-hour small-town opus, told across two separate but inseparable parts, released simultaneously last week. What Wang’s films have in common, beyond extended runtimes, is an unfashionable interest in everyday life. They’re as independent as their creator: movies that march to the beat of their own drum.

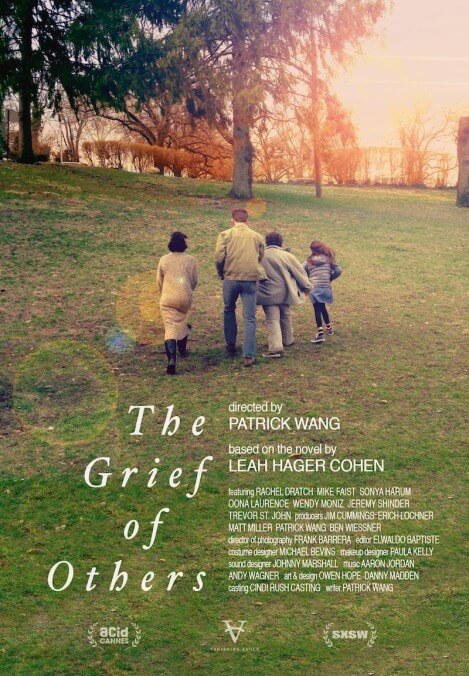

The Grief Of Others, which Wang made between those two epics, opens in select theaters today, three years after its premiere at South By Southwest and right on the heels of A Bread Factory. It’s every bit as human-scaled as the filmmaker’s other work—but also, in its noble restraint, a little less involving. Based on a novel by Leah Hager Cohen, the film concerns a family feeling its way slowly and uncomfortably through the mourning process. Parents John (Trevor St. John) and Ricky (Wendy Moniz) have lost their newborn son, who died about three days after birth of a cranial abnormality. The death has wedged some distance between the two. It’s also affected their other children: Grade-school-aged Biscuit (Southpaw’s Oona Laurence) cuts class, while bullied, overweight adolescent son Paul (Jeremy Shinder) shrinks from every conversation.

It’s telling that Wang neither conceals for a long period nor comes right out and immediately discloses the central tragedy, instead simply allowing that information to reveal itself organically. That’s reflective, too, perhaps, of the way the characters cope with it: not totally refusing to mention the loss, but also not addressing it much, either. The Grief Of Others might have thrived in this purgatorial aftermath, sketching in the particulars of a household determined to rush back into normalcy, to life as it was before. Instead, the film introduces an outside variable: Jess (Sonya Harum), John’s grown daughter from a past relationship, now pregnant herself. Invited to stick around until the child is born, she befriends a neighbor, Gordie (Mike Faist), who’s just lost his father. Neither subplot is as textured as the domestic drama at center; one wonders if they’d feel more specific with the extra hour Wang usually affords himself.

Most of the dialogue is plain, realistic, unaffected. Only occasionally does Wang succumb to a cliché: “You haven’t been home in a year,” John tells Ricky during one of the film’s few open spats. Stylistically, we could often be watching a movie from an earlier era, from a time when American indies were unflashy and unpolished, their own budgetary restrictions mirrored by the ordinariness of the lives they depicted. Is the drab bareness of the sets an extension of the movie’s minimalism or a matter of DIY necessity? Wang’s background in theater informs the black-box simplicity of the setups, in that a lot of this would work perfectly well on a cramped stage. Which is not to say that The Grief Of Others is free of flourishes; as with In The Family, the structure is occasionally nonlinear, fades and superimpositions idiosyncratically triggering flashbacks.

At times, one has to wonder if The Grief Of Others is too committed to its emotional integrity and lack of sensationalism to provide much in the way of actual drama. It might have benefited from some prickliness; even when John and Ricky spar, it doesn’t draw blood. More than Wang’s other works, this one feels lodged in a middle space, just like its characters: It’s at once artful and awkward, touching and a little dull. At least Wang builds to something significant—a coda that’s lovely and gently cathartic, a final shot laid over the penultimate one, as some long overdue closure subtly transforms the family’s shared space, suggesting a home partially reborn. Here, as always, Wang’s style feels beholden to no trends. It’s the right way to end the movie, in part because it’s a way only he would consider.