Only briefly does The Possession Of Hannah Grace exorcise Exorcist cliché

The Possession Of Hannah Grace begins with such a comprehensive assembly of exorcism-movie boilerplate that if the film possesses any ambition at all, it could only involve subversion. The opening scene has everything: a blue-black non-color palette, mournful Christian accoutrements, a young woman (always a young woman) tied to a bed, whispered intonations of “I know you’re in there,” a demon-voiced rejoinder from within its victim calling that young woman (again, always a young woman) a whore. It’s exorcism’s greatest hits, if exorcism were a band playing 300 casinos and state fairs a year.

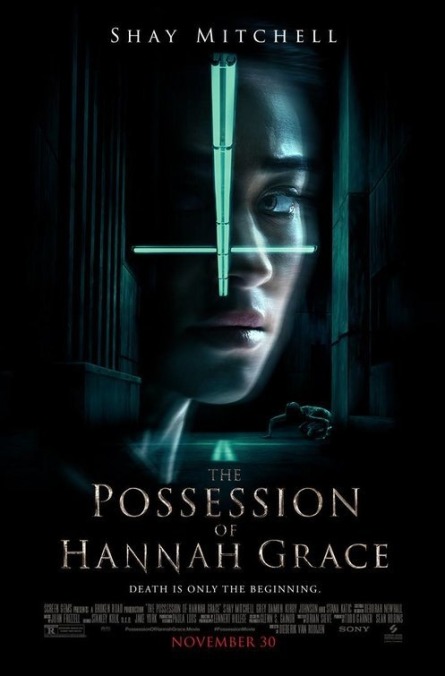

Hannah Grace inspires enormous if twisted gratitude, then, when the title character’s father (Louis Herthum) tearfully smothers his possessed daughter with a pillow, ending the demon’s reign of terror before the movie cuts to a different character entirely. Megan (Shay Mitchell) is a former cop and recovering addict who hopes to strengthen her grip on sobriety with a new job at a Boston hospital’s morgue, accepting cadaver deliveries over the graveyard shift (yuk yuk, as well as yuck yuck). In what turns out to be the movie’s one clever conceit, Megan receives the mangled corpse of one Hannah Grace. And did she just see it move out of the corner of her eye? A story that briefly looked like every exorcism movie ever made suddenly becomes a sequel of sorts to every exorcism movie ever made.

Any demon-possession story that unchains itself from the bedroom is worth looking into, and Possession Of Hannah Grace has the elements of a good, no-frills horror exercise: a (fairly) novel angle, a creepy single location, a convincing performance from Mitchell, and a trim 85-minute running time. So it’s disappointing when the movie quickly starts offering what it thinks are frills: extra characters, extra kills, extra noise. The would-be scares feel like they’ve been lifted from the dozens of movies that supplied the clichés of the opening sequence. They’re dropped into Hannah Grace without much regard for either physical or psychological atmosphere.

Director Diederik Van Rooijen engineers some small-scale frights when he sends shadowy figures brushing through the background of the frame, beyond Megan’s field of vision. He also generates a running shiver based on the morgue’s use of motion-activated lights that come on with a sickly buzz and flicker (not especially likely for such a cavernous, clean facility, but allowable by horror-movie license). But most of the movie’s creepy overtures are bluntly obvious—menacing thumps, rather than barely perceptible twitches. They’re poorly designed for a story that’s supposed to nag at Megan with doubt over what she sees in front of her, seeded by a vaguely poor-taste backstory in which she’s haunted by an inability to fire on a suspect in the field during her cop days. Most of the supporting characters thump, too, broadcasting their traits so loudly and insistently that they seem expressly designed as malicious demon fodder, whether or not they actually meet that fate.

The eventual body count is one of the dullest things about this movie, especially when it halfway frames its central threat as a manifestation of depression and anxiety. At least that’s the reading that could explain why the demon—the fully possessed body of poor Hannah Grace—spends so much time skulking around the hospital morgue at night when it seems fully capable of going on an unencumbered rampage. (If these demons really can be threatened by priests, it makes a kind of clever sense to fake its death alongside the host body, and get the hell away from those bedposts.) The movie eventually sort of explains that it needs to feed on its victims to gain strength, furthering the depression metaphor. But the thing reaches superhuman abilities almost instantly, and the movie never escalates its tussle with Megan into a Babadook-style battle of wills. It just rattles around the morgue cabinets before going in for listless kills.