Open Windows attempts to disguise a revenge movie in a voyeuristic techno-thriller

Each of Nacho Vigalondo’s features has been predicated upon the chemical reaction between two wildly disparate but equally seedy genres. Timecrimes, the clever sci-fi story that first introduced the Spanish filmmaker to a global audience in 2007, compounded the pretzeled logistics of a time-travel movie with the sharp pleasures of a slasher—it was a hell of an experiment, and Vigalondo has been desperately trying to replicate the results ever since. 2011’s Extraterrestrial, a diverting romantic comedy set during an alien invasion, failed to spark the same alchemy. Open Windows attempts to disguise a revenge movie by cloaking it in the flash of a voyeuristic techno-thriller, but the combined concepts are so high that the film resolves as Vigalondo reaches his Icarus moment, the corpse so mangled and unpleasant the project’s ambition can only be identified via dental records.

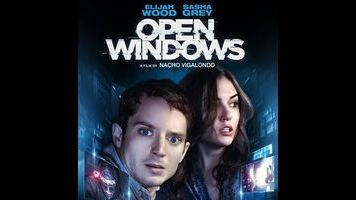

At its most superficial level, Open Windows chronicles one wild and crazy night in the sad life of Nick Chambers (Elijah Wood), a nerdy blogger who’s won a contest to have dinner with his favorite B-movie starlet, Jill Goddard (Sasha Grey, and it’s pronounced “Godard”). Nick is a veritable obsessive, and the wide-eyed sucker doesn’t seem the least bit concerned that his lust object’s latest film—a cheap zombie wank called Dark Sky: The Third Wave—looks unwatchable, but his blind fandom is merely the first clue that things are not as they seem.

As Nick prepares for the evening, recording a video introduction from inside his Austin hotel room, a strange link appears on his laptop. Upon clicking it, Nick is confronted by the broadly menacing British voice of a man named Chord (Neil Maskell), who tells the feckless hero that the contest has been canceled, and that Nick has flown all this way for nothing. But Chord doesn’t stop there. He invites Nick to click on a second link, which grants the gutted fan full access to Jill’s phone, including the ability to watch her through its built-in camera. Within a few minutes, Chord has transformed Nick’s computer into a computer-age panopticon that’s been designed to monitor a single prisoner, hacking every conceivable electronic device in range until Jill’s privacy disintegrates completely, every part of her world exposed on the screen of Nick’s laptop.

And then it becomes clear that everything in the movie is appearing on Nick’s computer (including Nick himself), and that the “open windows” of the title refer not to the glass divides that might keep a thief out of a house, but rather to the intangible boxes that separate the contents of a monitor, and serve as portals through which people can slip into the lives of others. Indeed, the vast majority of the film is confined to the playground of a digital display, Vigalondo telling his story against the backdrop of an intricately designed cyber landscape that feels as true to the potential of contemporary computing as Lucy did to the potential of the human brain.

Vigalondo had originally intended to make Open Windows before Extraterrestrial, but his story outpaced the tools required to bring it to life, and the visual density of the finished product makes it easy to appreciate why. But technology always improves with time—scripts don’t. Vigalondo’s script may not be as important to him as the gimmick through which it’s told, but the diminishing returns of the film’s means only serve to underscore its hackneyed and uninvolving ends.

The conceit, along with Nick’s increasingly complicit role in Jill’s violation, taps into a number of interesting (and unfortunately topical) issues regarding how the Internet has provoked a male entitlement over the female body—it’s telling that Jill begins the film as a prize for Nick’s “nice guy,” and even more so that Chord manipulates Nick by seducing him into playing the victim. That Jill is played by former porn star Sasha Grey adds an obvious wrinkle to the dynamic, as a scene in which the actress is forced to strip is compellingly complicated by how her past career (and the ready online availability of her naked image) might confuse audiences into thinking they’re owed more of her body. It’s the film’s hyper-codified gaze, and precious little else, that distracts from the underlying fact that Open Windows is just stale found-footage junk with better graphics.

As the story spins out of control, the lack of a practical reality begins to take its toll, the detachment sucking the fun out of a movie that is always sweating harder and harder to deliver it. Each twist frays the connection to Vigalondo’s film world, and by the time the film pits three rival hackers against one another (including one who sounds distractingly like an Auto-Tuned Kiefer Sutherland), the whole thing is as dull as it is ridiculous. For the rambunctious and imaginative Vigalondo, Open Windows is just another failed experiment, and it leaves him with that much more to prove.