A little over a month ago, Brett Kavanaugh sat in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee and delivered an angry, disqualifyingly partisan diatribe in which he not only denied the sexual assault accusations against him but also expressed outrage that he’d even been obligated to respond. “This is a circus,” Kavanaugh fumed. “The consequences will extend long past my nomination. This grotesque and coordinated character assassination will dissuade confident and good people of all political persuasions from serving our country. And as we all know in the United States political system of the early 2000s, what goes around comes around.”

According to The Front Runner, it’s coming around right now after first going around back in 1987, when Gary Hart, then widely considered the likely Democratic nominee for president, abruptly dropped out of the race following reports that he’d had an affair with a young woman named Donna Rice. Obviously, Jason Reitman, who directed the film and cowrote the screenplay (with Jay Carson and Matt Bai, adapting Bai’s book All The Truth Is Out), couldn’t have anticipated the Kavanaugh brouhaha; The Front Runner premiered at Telluride in late August, two weeks before Christine Blasey Ford’s charge of sexual assault went public. Nor is the analogy precise, since Hart’s denials were less categorical, pivoting largely on the notion that his private life was none of the public’s business. Nonetheless, what we have here amounts to Brett Kavanaugh Was Right: The Movie, along with fuel for Donald Trump’s incessant and irresponsible refrain that the “fake news media” is the enemy of the people. This would have been the wrong angle to take on Gary Hart’s story at any time, but it’s especially pernicious right now.

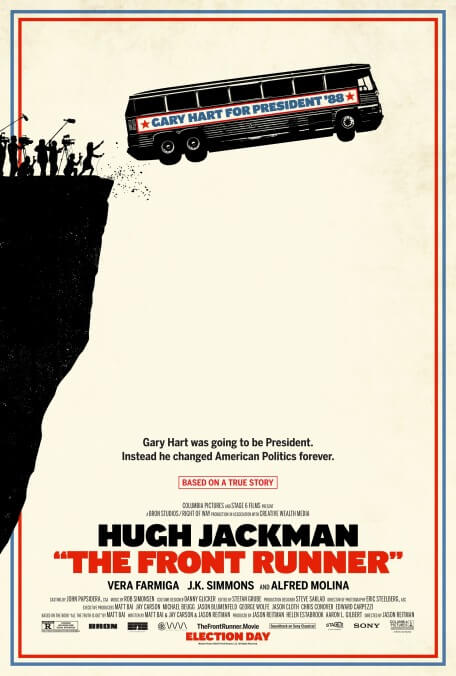

It doesn’t help that Reitman, returning to the breezy pseudo-cynicism of earlier films like Thank You For Smoking and Up In The Air, has made The Front Runner so superficially entertaining. Apart from a brief prologue set in 1984, the film takes place entirely during the week or so leading up to Hart’s withdrawal, and devotes as much fast-paced, Sorkin-inflected attention to various journalists and harried campaign staffers as it does to Hart himself (played by Hugh Jackman, who accurately dials down his own charisma only about 20 percent for the role). Already plagued by rumors of womanizing, Hart, in a moment of exasperation, invites reporters to go ahead and follow him around, insisting that anybody who puts a tail on him will “be very bored.” As it happens, between his issuing of that challenge and its publication, the Miami Herald does just that, on its own initiative, having received an anonymous tip about Hart’s relationship with Rice. Its reporters are not bored. (The Herald then uses Hart’s quote as justification for staking out his D.C. apartment, even though they only learned of what he’d said afterward.) Hart does his best to stonewall for a few days, encouraged by polls suggesting that the public is on his side, but ultimately chooses to suspend his campaign, giving a speech that Kavanaugh would echo decades later. “We’re all going to have to seriously question the system for selecting our national leaders,” he bitterly noted, “for it reduces the press of this nation to hunters. […] And then… ponderous pundits [wonder] in mock seriousness why some of the best people in this country choose not to run for high office.”

In other words: Leave Britney alone! Reitman and his cowriters aren’t stupid—they make a point of having Rice (Sara Paxton), who graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University Of South Carolina, lament the way that she’s perceived as a brainless bimbo, and they give Hart’s wife, Lee (Vera Farmiga), the opportunity to rip into him for his thoughtless stupidity. One line of dialogue about the responsibility of powerful men is so anachronistically woke as to be downright jarring. For all that, though, The Front Runner fundamentally argues that the Miami Herald did Hart and the American people a grave disservice by exposing the affair, permanently cheapening political discourse. The movie agrees with Hart: It’s none of our business. Legitimate questions about whether candidates should live up to the moral ideals they espouse, and whether daring reporters to follow you around while you’re having an affair reflects judgment poor enough to disqualify one from running an entire country, are raised and then quickly dismissed. Emphasis instead falls squarely on the notion that Gary Hart got a raw deal, having been forced to quit for committing the same forgivable sins that the press had overlooked with Kennedy, Johnson, and others. We let it slide then, The Front Runner suggests, and everything was fine. Why can’t we let it slide now? If we insist on scrutinizing candidates’ sexual history, pretty soon we might not have any candidates at all.

What’s particularly frustrating about this blinkered viewpoint is the way that it brushes against, but then blithely ignores, something that’s genuinely relevant to 2018: the dizzying speed with which public opinion can sometimes shift, abruptly changing the rules about what’s considered acceptable behavior. At one point, when Hart suggests simply ignoring all of the salaciousness and sticking to the issues, his campaign manager (J.K. Simmons) tries to explain that it’s outmoded thinking. “This isn’t ’72,” he tells Hart. “It’s not even ’82.” Change the years and you can imagine similar remarks being made to disgraced celebrities post-Weinstein. Suddenly, people won’t tolerate violations that they’d always been willing to overlook. That’s well worth exploring, especially in a historical context. But The Front Runner isn’t about a man who learns the hard way that certain ethical lapses will no longer be so easy. It’s about a man who was unfairly penalized for doing the same thing his predecessors got away with for decades. It’s a feature-length whine of frustrated entitlement. A movie less suited to its cultural moment would be hard to imagine.