Oral history Changes is a grounded account of Tupac Shakur’s legendary life

Nearly 25 years after his murder in September 1996, Tupac Shakur elicits complex feelings. Fans across the world praise him as one of the greatest—if not the greatest—voice in hip-hop history. Meanwhile, his musical legacy is often overshadowed by a war of words that may have led to the March 1997 murder of the Notorious B.I.G., a legendary beef that some East Coast rap fans never forgave him for. A 1994 sexual assault conviction sits uneasily with two of the best tributes to women in the rap canon, “Keep Ya Head Up” and “Dear Mama.” His Black Panther family history belies his final year on earth as an aggrieved, money-flouting “baller” who lashed out at enemies real and perceived, a dichotomy fiercely debated in the press at the time. Yet he remains a hero of activists, and his music was widely played at the George Floyd protests last summer.

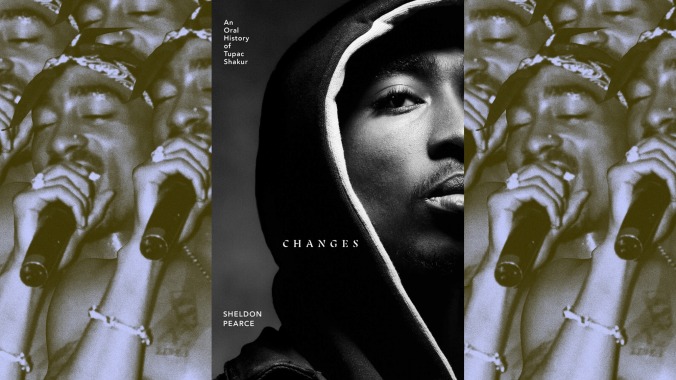

Sheldon Pearce’s Changes: An Oral History joins a bookshelf already teeming with 2Pac arcana, from rhapsodic praise like Michael Eric Dyson’s Holler If You Hear Me: Searching For Tupac Shakur to neoconservative hit jobs like Armond White’s Rebel For The Hell Of It: The Life Of Tupac Shakur. “Pac is among our most well-studied figures,” Pearce, a writer and editor at The New Yorker, acknowledges in a brief author’s note. But instead of speaking with highly publicized figures in his life such as Sean “Puffy” Combs and the late Shock G, he elicits testimony from more than 50 individuals who knew and met Tupac, covered him as a subject in the mid-’90s, or are simply latter-day admirers of his work. The result is a book that quietly tries to humanize an oft-mythologized figure. “This oral history is less about all-inclusive, full-scale documentation and more about texture—about getting to the heart of what Tupac meant to people, how his life came to reflect so different truths,” writes Pearce.

Still, oral histories can have their drawbacks. At best, they create a three-dimensional portrait more dynamic than a standard biography, replicating the countless individual interactions that comprise someone’s public persona. Yet they often drown in noise as a bunch of people with tenuous connections to the subject opine in loud and contradictory ways. Pearce mostly avoids the latter, particularly in wonderful early chapters where Tupac’s former teachers and friends describe his youth in New York, Baltimore, and Marin City, California. In a section that covers Tupac’s return to New York—a pivotal, chaotic era where he befriends the Notorious B.I.G. as well as sundry gangsters while filming the movie Above The Rim, is charged with rape after a nightclub incident, and is shot by assailants at Quad Studios—Pearce maintains calm by bringing in figures like longtime journalist Rob Marriott and scholar Mark Anthony Neal. But the book’s climax, which covers 2Pac’s shooting and subsequent death in Las Vegas, can’t help but descend into LAbyrinth-style speculation and conspiracy theories.

Changes may fail to fully explain the motivations for this most enigmatic of superstars, no matter how many times the book’s chorus points out that Tupac was a Gemini. But at least it makes him seem more flesh-and-blood than the countless statues and murals that pay tribute to his brief yet incredibly eventful life. These four key moments stand out amid all the chatter.

“Most people didn’t know he was an actor first”

Changes has several great anecdotes from Tupac’s fellow actors, students, and teachers. Levy Lee Simon, who performed alongside a 12-year-old Tupac in a production of A Raisin In The Sun at New York’s Apollo Theater, reminds us, “Before he ever entered into the hip-hop world, he was an actor.”

Tupac’s detractors might take this as further evidence of the rapper’s purported “fake gangsta” rep. But they shouldn’t. There’s a lengthy history of rappers who acted in plays and films as children, like Lauryn Hill and Mos Def. Hip-hop is as much about performance as music, and you’ve got to get experience somewhere.

“You couldn’t have said it in ‘Dear Mama?’”

Despite Tupac’s world-burning rivalry with the Notorious B.I.G., he nurtured friendships with New York rappers like Naughty by Nature and Boot Camp Clik. Instead of those famed acts, Pearce turns to Pudgee The Fat Bastard, whose name will mostly resonate with knowledgeable ’90s rap fans. When Tupac shouted out Pudgee in the infamous Bad Boy diss “Hit ‘Em Up,” it caused problems for the Bronx rapper. “It was at a time where people were shooting everybody,” says Pudgee. “So even though I felt so good that my friend said my name, I was like, ‘You couldn’t have said it in ‘Dear Mama’?”

“Tupac feared for himself and protected himself”

In a lengthy section covering Tupac’s sexual assault trial and conviction, Pearce presents commentary by one of the jurors, Richard Devitt. He claims that one juror was “senile” and another had a crack addiction. Then he says the panel wanted to acquit Tupac, but one “devout, extreme, right-wing Roman Catholic” woman insisted on finding Tupac guilty. In the end, they compromised on a lesser charge of fourth-degree sexual assault. “Our knowledge of fourth-degree sexual assault is that if you put your hands on somebody in a bar or something like that, that’s fourth-degree sexual assault,” alleges Devitt, adding that the group was surprised when the judge sentenced Tupac to one and a half to four years.

The section is arguably Pearce’s finest work in Changes as he attempts to balance views of Tupac’s innocence with respect for the survivor. At one point, journalist Justin Tinsley notes how Tupac admitted in a 1995 Vibe interview that he should have done more to protect the woman, who was allegedly gang-raped by newfound gangster friends after he had had consensual sex with her. “At least in terms of that situation, Tupac feared for himself and protected himself over protecting” her, says Tinsley.

Despite Pearce’s tact, it’s still missing the voice of the survivor herself. In a 2018 interview with DJ Vlad, she asserts that Tupac was directly involved in the assault. Quotes from it could have been shared in a sidebar, a rebuttal tactic Pearce uses elsewhere for less-pivotal figures like Vanilla Ice and the late John Singleton.

“Dear Queen”

A section that covers Tupac’s stint in prison opens with Wendy Day, a lawyer and music industry activist who helped Tupac negotiate contracts. She recalls her first experience with Tupac—standing in a queue at New York nightclub the Palladium as he and his friends loudly catcalled women, and being so disgusted by his behavior that she moved back in the line. When the two exchanged prison letters, she recalls, “I basically said to him, a lot of what you do you bring upon yourself, and then you complain in the media that people are profiling you.”

Day then reveals how Tupac eventually disarmed her and they became friends. “When a letter came back to me… it was so respectful. I think it started ‘Dear Queen,’ and it was so humbling,” she says. “His response was: Here’s where I come from. This is the kind of life I had. Here’s why I’m the way I am.” The passage illuminates how Tupac Shakur continues to attract followers because of his well-documented strengths and faults, not in spite of them.