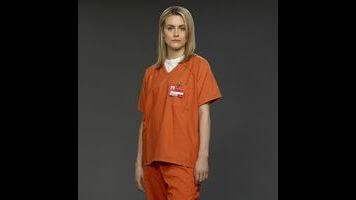

Orange Is The New Black: “Can’t Fix Crazy”

“It’s not like she’s going anywhere.”

In trying to convince Larry not to marry Piper, his parents take a pragmatic approach. While they plant the seeds that Larry is in love with the idea of Piper, and hasn’t thought through what values she holds, they ultimately rest on the above argument: Why rush something when you can just wait and see what happens?

What Larry’s parents don’t understand, and which Larry himself has only recently started to grasp, is that prison is somewhere. It’s easy to think about prison as a space where you are isolated from everything, and thus a place where your life simply stops until you re-emerge sometime later. Larry’s parents warn about the possibility of someone murdering Piper for looking at them the wrong way, but they don’t understand that the most transformative changes in prison aren’t the result of dropping the soap. Those changes are the result of people living in a space where their understanding of their own selves is consistently being judged, tested, and broken down.

Orange Is The New Black is always better when it’s focused inside Litchfield, but in “Can’t Fix Crazy” it’s important to get the perspective of someone who has no idea what goes on inside those walls. It emphasizes the degree to which thirteen episodes have conditioned us to see prison in terms different than those who haven’t been following the evolution from “Crazy Eyes” to Suzanne, while simultaneously reminding us that not everyone has that same perspective on the prison system. A number of recent articles criticizing the series for its engagement with stereotypes tied to the prison system do the show a disservice not because they are false—the show actively engages in stereotypes of race, sexuality, and gender—but rather because they stopped watching the show before it could transform itself into a show about people instead of a show about prison (even if I would argue they achieved this in earlier episodes that were watched by at least one of those authors).

“Can’t Fix Crazy” offers one of the sweeter stories yet, as the series’ supporting cast bands together for a nativity pageant in time for the Christmas holidays, and a group of inmates organize a Secret Santa gift exchange. These are the kind of stories you would tell in any television drama, and reflect the fact that for some women, prison is their home. There’s a great conversation where the idea of adding Piper and Alex to the Secret Santa list is met with resistance not because of any deep dislike for the two women, but rather out of the feeling that Secret Santa is something reserved for those who have truly become part of the “family.” And while that family is organized around racial lines (consisting as it does with Red’s group of white women), the Christmas pageant brings together the whole prison for a combination of hilarious auditions and a final uplifting song where always-silent Norma Romano—played by Annie Golden, formerly of The Shirts—suddenly breaks out into song to save Suzanne from an embarrassing moment and bring everyone together. It’s spiritual, it’s powerful, and for all of the people in the audience—including many prison employees—it’s a glimpse of the community that can subsist within the chaos of the prison system.

It’s also all a lie. This is not to say that the tidings of comfort and joy the inmates bring through song are disingenuous, but rather to suggest that they cannot be sustained. Orange Is The New Black has sought out moments like this one, or comic moments like the Scared Straight sequence, as a way to show a different side to inmates as their time in prison becomes less about why they’re there or when they’re getting out, and more about how they live day-to-day. It wants to normalize the prisoners, and creates narrative spaces in which they can act like human beings. However, what Orange Is The New Black hasn’t done is attempt to normalize prison. At the same time as the inmates are joining voices to celebrate the season, Piper and Pennsatucky are outside in the snow with a cross and a screwdriver dueling to the death.

That final scene is the part of “Can’t Fix Crazy” that bothered me. Pennsatucky’s quest for revenge felt like plot for plot’s sake, the character going full nutso for the sake of building to a thrilling climax that places Piper’s future in jeopardy. It reframes the character of Pennsatucky as she was before we learned more about her, treating her like a cartoon villain instead of a real character (which has always been a danger with Taryn Manning’s performance, which I loved up until it was deployed in this fashion). The scene offers itself as evidence of Piper’s (d)evolution: Whereas Larry’s parents believed she could become the victim of a prison-related crime simply by looking at someone the wrong way, the Piper Pennsatucky confronts at episode’s end has lost her fiancé and her lover in the span of just a few days. She has been stripped of everything that once defined her, which makes it easier for her to throw caution to the wind and beat the living shit out of Pennsatucky once she gains the upper hand (and after Healy chooses to walk away to leave Piper to her fate). This scene makes a lot of sense as a pivot point in Piper’s journey, in other words, but it doesn’t feel in service of the rest of the show—instead, it feels in service to the “plot” necessary to make the show function, but also a space where the nuance of character development got lost beneath the bloodshed.

By comparison, an incident like Tricia’s death—despite being similarly plot-heavy—didn’t feel like it was flattening any characters involved. The same goes for Red’s storyline in the finale, which is similar in its motivations. Like Pennsatucky, Red believes that she has been wronged, and is going to do what she can to ensure that she gets put back in her rightful place and gains restitution. Red’s actions also result in bodily harm, as her attempts to sabotage Gloria and the Latina inmates’ new kitchen rotation results in a grease fire that injures Gina. But whereas Pennsatucky takes a left turn into her homicidal tendencies, Red represents a different kind of danger. It reminds me of when Claudette caught Tricia trying to frame Mercy with Pornstache’s drugs in order to force her to stay; in an effort to survive herself, Tricia was willing to destroy the woman she loved and force her to remain at Litchfield. As much as I may judge the characters for their actions—or attempted actions—in those instances, part of the show’s purpose is getting us to explore why those kinds of things happen in prison. And by the time the season came to its conclusion, I could see how Red would take extreme action when everything that defines and sustains her is ripped away from her, and thought there was something writerly but poetic about Red—like Piper back in “I Wasn’t Ready”—being refused service at the cafeteria for her actions.

If the season was building to a showdown between Piper and Pennsatucky, I wanted both sides of the conflict to have a story behind them, and I wanted to have a reason to believe that Pennsatucky wasn’t a complete loose cannon. It’s frustrating particularly because I hated to see Piper as a victim—which I did when she’s being threatened with death—given how much I hated her actions throughout “Can’t Fix Crazy.” When she fits in Fig’s office, she is in an immense position of power. Larry’s public radio interview has revealed Fig’s corruption, and forced her into taking measures to repair the prison’s reputation and reinstate the GED program. She is finally in the position she imagined the WAC would provide, and which she envisioned when she first got into prison. And so it is an incredible indictment of Piper that she so quickly chooses to use her leverage in order to get a marriage certificate; I understand the decision given how she has panicked while her relationships fall apart, and I know it’s an argument for why it’s so difficult for anyone in prison to change the system, but it made me want to root against her in that final battle, but rooting for Pennsatucky when she’s on a poorly justified murderous rampage never felt like a realistic proposition.

“Realistic” is an interesting word for Orange Is The New Black. Although based on a true story, much of the actual “plot” of the series is entirely fabricated, and “Can’t Fix Crazy” is one of the points in the season where it felt fabricated. This is not to say that this is inherently a bad thing, but whereas the Christmas pageant took something arbitrary and turned it into something emotional and transcendent, the plot-heavier side of things never resonated with me the same way. I don’t care about Larry enough for his confrontation with Alex or his breakup with Piper to register on any deep level, even if I agree with Alex’s conclusion that Piper is a problem herself. While none of these scenes were actively bad, they reinforced that my real appreciation for Orange Is The New Black comes not through its overarching narrative but through its small moments, like Sophia’s Christmas card from her son or Suzanne ice skating for her audition.

It is good for Orange Is The New Black that I was unsatisfied with “Can’t Fix Crazy” in the way that I was. This may seem counterintuitive, but the “reality” of the show is that nothing can just stay in that comfortable space of day-to-day observation. My attachment to Bennett and Daya’s relationship came from when it was a series of small moments, brief glimpses of humanity in an environment that actively seeks to strip inmates of their humanity. And yet over time their relationship became more complicated, and the larger picture revealed itself to be one involving an elaborate scheme in which Daya gives up her body, which has the effect of retroactively reframing all of those small moments as steps toward an ugly and messy situation that will end well for no one. No matter what romance they felt, the system—perhaps rightfully so, in this case—is designed to work against those small moments, and it is in the series’ best interest to condition us for that reality. While more nuance in Pennsatucky’s actions could have given the storyline greater substance from a character perspective, her fight with Piper nonetheless acknowledges that this show is not free from the dangers of prison that truly can sneak up on you at any moment.

If prison is indeed somewhere, it’s somewhere that’s fucked up, and no amount of charming auditions or “Shakespeared Straight” or renditions of “O Come All Ye Faithful” can change that. Instead, they must co-exist, as they have productively throughout the series’ first season. Todd VanDerWerff has already offered his thoughts on the entire season last month, and so I don’t want to dwell too heavily on the season as a whole. However, what I will say is that Orange Is The New Black’s first season contained an incredibly high volume of characters whose stories I feel I need to hear. Throughout its first season, the writers struck that all-important balance of making the argument for why its stories were important while simultaneously making those stories compelling. It also went out on a limb not only in primarily telling stories about women of color and queer women, but also in developing incredibly minor subplots for minor characters. For all of the concerns that this would simply be Piper’s story, concerns that even popped up for me at points during “Can’t Fix Crazy,” the sheer breadth of stories told makes Orange Is The New Black far more than one woman’s story, and a tremendous start to a series that has the potential to grow even richer in future seasons.

Stray observations:

- Now that we’ve reached the end of this expedited but nonetheless not “binge-friendly” way of covering the show, were there moments in earlier reviews where you were desperate to talk about something in the finale but you resisted because you are nice and respected the spoiler-free policy? Let’s talk about those moments now.

- In terms of next season: Are we expecting a time jump to when Piper is released from solitary? Will that help the show deal with Laura Prepon stepping away from the show for much of the season? How do we interpret the various deals for actresses to become series regulars in regards to their placement in the story? Lots of room for speculation, much of which has probably already happened with Todd’s review but feel free to further elaborate below.

- “You just get used to having cold feet that ain’t magenta”—Morello, winning at Secret Santa.

- “This place fucking stinks”—Bennett has determined that his situation (stuck between Caputo and Fig, dealing with the Daya’s pregnancy) is endemic of Litchfield, but he’s too personally involved to see that it’s a more widespread problem with the system.

- “I can sing too, in addition to the ice skating”—never change, Suzanne.

- “Don’t be talking about tampons when I’m plotting my revenge”—In context of earlier Pennsatucky scenes, this worked; here, I thought it too broad. Such is the dangerous dance of the dramedic.

- I enjoyed this quick audio response to the finale from my colleague Ryan McGee.

- Thanks to everyone who has patiently but passionately been discussing the show over the course of the past six weeks—I know the Netflix model sort of throws a wrench into how we normally cover television, but I really appreciate many of you embracing our experiment and diving in on a weekly basis. See you for season two sometime in the spring.