Orange Is The New Black: Orange Is The New Black

Orange Is The New Black debuts at midnight Pacific time Thursday on Netflix. This review is written based on the first six episodes. Our review of the full season will go up later in the week or early next week, and Myles McNutt will review two episodes a week through the end of the summer.

The best art creates a place that you go to when you indulge in it. It’s a mental space you move into, the contours of which are hammered out by the sounds of the strings in Beethoven’s 9th or the frozen looks of terror on a peasant’s face in a painting by Hieronymous Bosch. Television has always been uniquely good at this because it combines the best aspects of film—the literal presentation of the world the viewer enters—with literature—the time it takes to truly build that world out and get lost in it. Yet so few television shows take advantage of that ability, and some that try make things look far too clumsy. There’s a value in minimalism, and there are a great many TV shows over the decades that keep the scope laser-focused, but when a series can create a whole alternate universe for viewers to step into, that’s when television can be at its most powerful.

Of all the creators on television to create an alternate world that’s truly involving and enveloping, however, few might have picked Jenji Kohan to pull off the trick. Kohan, late of Weeds, rarely rose above the most superficial aspects of that show’s setting, indulging in easy, occasionally smug suburban satire that seemed designed to validate its audience for seeing through the hypocrisy of its setting. The show was worth watching for its performances—particularly Mary-Louise Parker’s often incredibly powerful one—and for its occasional story turns, but it was at almost all times too content in what it thought it knew, certain of its superiority to too many of its characters and too much of its world. When the series left behind its early suburban-satire years, it collapsed not because it buried the premise but because it tried to build a show less around characters and setting and more around a sensibility, and there’s rarely any gas in that engine. It tried to turn archness into story fuel, and that eventually got to be too much.

Kohan’s new series, Netflix’s Orange Is The New Black, seemed unlikely to escape this particular problem, simply because it was based on a memoir by Piper Kerman, just another book by a white person who slips into the sort of world the upper-middle class is supposed to avoid by virtue of its upbringing, then proceeds to make the adventure All About Them. (To her credit, Kerman has done some valuable things in terms of advocacy on drug sentencing and the like, but her writing on the experience has suffered from the same archness that plagued Weeds.) Instead, Orange Is The New Black is one of the best new shows of the summer, a fully realized and presented TV series almost from the word go, and the first Netflix original project that makes the big “next episode” button that pops up at every episode’s end all too easy to click. Where both Weeds and the book the series is based on fell too in love with their own certainty, the TV version of Orange Is The New Black is about discovery, about the sorts of people who too often fall through the cracks, and it’s told with almost painful earnestness by voices that are rarely presented on our televisions. It’s also frequently whimsical, surprisingly funny, and deeply moving.

Orange Is The New Black is also a great argument in favor of binge-viewing. Where House Of Cards was essentially a standard cable drama mostly notable for its presentation and the fourth season of Arrested Development argued in favor of the binge due to its incredible structural complexity, Orange Is The New Black creates the compulsive need for binge viewing thanks to the way it smartly structures its season. In the six episodes sent out to critics, Orange takes a page from the Lost model, filling in the backstories of the various women in the prison at its center, their pasts adding to the complexity of the mosaic in the present. The storytelling is never as ambitious as Arrested Development’s, but the scope is impressive. Kohan and her collaborators slowly tease out every corner of this prison and fill in pieces of backstory in episode six that inform relationships from episode one. Prison isn’t the blogging project the protagonist almost seems to mistake it for early in the first episode or a place where her past won’t matter. For as much as everyone in the prison says what happened to put them there doesn’t matter, it clearly does. Prison isn’t a place to atone for your history or even forget about it; it’s a place where that history comes fully to bear and forces you to come to terms with who you really are.

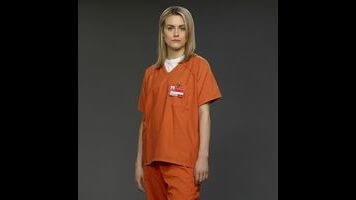

The most notable thing Kohan has done is strip-mine Kerman’s book for spare parts and simply start telling her own stories. Yes, there are characters and moments throughout the episodes that will ping those who’ve read the book with recognition, but for the most part, this is fresh material, or at least so thoroughly remixed material that it doesn’t have the onus of needing to hew close to what really happened. As Kerman stand-in Piper Chapman, Taylor Schilling finally lives up to the many, many attempts Hollywood has made at making her happen, carefully walking the tightrope between earned obliviousness—of the sort that a comfortably spoiled white woman would naturally have—and ever becoming unlikable. There’s a magnificent moment in the first episode where Piper (now “Chapman” to her fellow inmates) fakes tears to get to call her fiancé, Larry (Jason Biggs, doing his best with the show’s weakest material), and Schilling plays the moment when those fake tears become real ones perfectly. Piper’s been scared of going to prison, sure, but she’s also treated it just a bit like an adventure, something she can write about later. In that moment, she realizes she hasn’t just lost her freedom; she’s lost her ability to define herself. She is, increasingly, what others say she is, and she has to put up with it. (The series is never overbearing on the need for prison reform, but the advocacy-aimed aspects of Kerman’s book are present and accounted for.)

Yet Piper’s just one of dozens of characters—nearly all female, nearly all non-white—the show wants to tell the stories of, and it’s here that the series really shines. Using the sort of TV main character audiences are used to, Orange Is The New Black becomes a frank depiction of the sorts of women who seem destined to be lost in the system, from an old Russian immigrant chef (Kate Mulgrew) to an African-American transgendered hairdresser (Laverne Cox), whose wife seems more thrown by her former husband becoming a criminal than becoming a woman. At every turn, Orange Is The New Black is filled with richly portrayed, complicated characters, of all races and creeds, and the show takes both their crimes and their desire for atonement seriously. It’s the kind of series that can present a chicken as a symbol of hope and actually earn that symbolism because it’s so damned forceful in its presentation. Schilling is a good, often magnetic, center for this series, but she’s also there to get viewers to consider other perspectives and viewpoints, something rare in a television world that seems increasingly closed off from lower- or even middle-class economic anxiety, to say nothing of poor non-whites.

Orange Is The New Black is also wonderfully insightful and complex when it comes to sex, notably Piper’s complicated sexual history. The crime that landed her in prison was smuggling drug money to help the girlfriend she had straight out of college (Laura Prepon). Though Piper is now engaged to a man and about to open the most upper-class white person business one could think of (selling designer soaps), her complicated, dangerous past and her lesbian relationship aren’t treated as flings. They’re treated as integral parts of her being that she’d hoped to set aside but finds resurfacing once she’s in prison and forced to confront the full weight of her past. Bisexual women are too often presented in fiction as women who are simply waiting to meet the right guy, but Orange Is The New Black understands how complicated this all can be. Piper really loved her ex-girlfriend; she really loves Larry. Both of those emotions are genuine, and neither is more genuine than the other. Her stint in prison, then, becomes less about owning up to something she did and more about accepting who she was and still is, in all its messy pieces. (The series is also refreshingly frank about lesbian relationships in many of its other characters, particularly Natasha Lyonne as the gleefully blunt Nicky.)

Orange Is The New Black has problems around the edges—the satire gets a little too thick and Weeds-like whenever Piper’s old life comes calling, and it has yet to figure out how to integrate Larry in anything like a satisfying way (the real Larry kept updating Kerman’s blog, which wouldn’t make for riveting television)—but whenever it threatens to skew too far into cutesiness or preciousness about its world or its characters, there’s a bracing reminder of the stakes of this series, of the price of atonement. And always there’s the prison, as skillfully realized a world as a TV series has had this early on in many years. It’s, at all times, a grim, colorless monolith, keeping the characters in but also binding them together, making them—and us—see the world through different eyes.